Gorgeous Gulf of Alaska Seen from Space (Photo)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

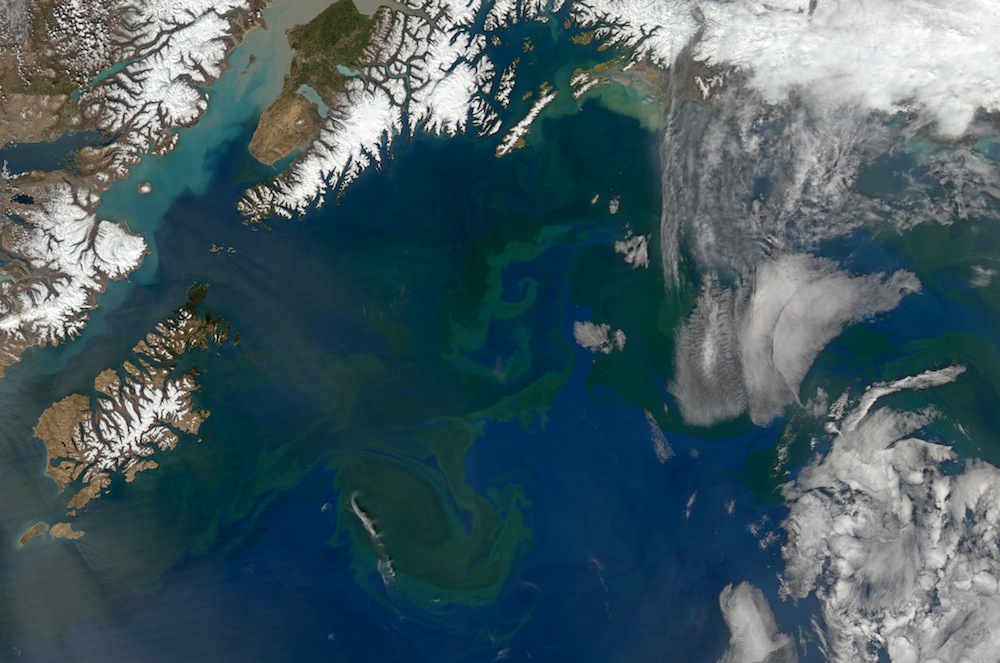

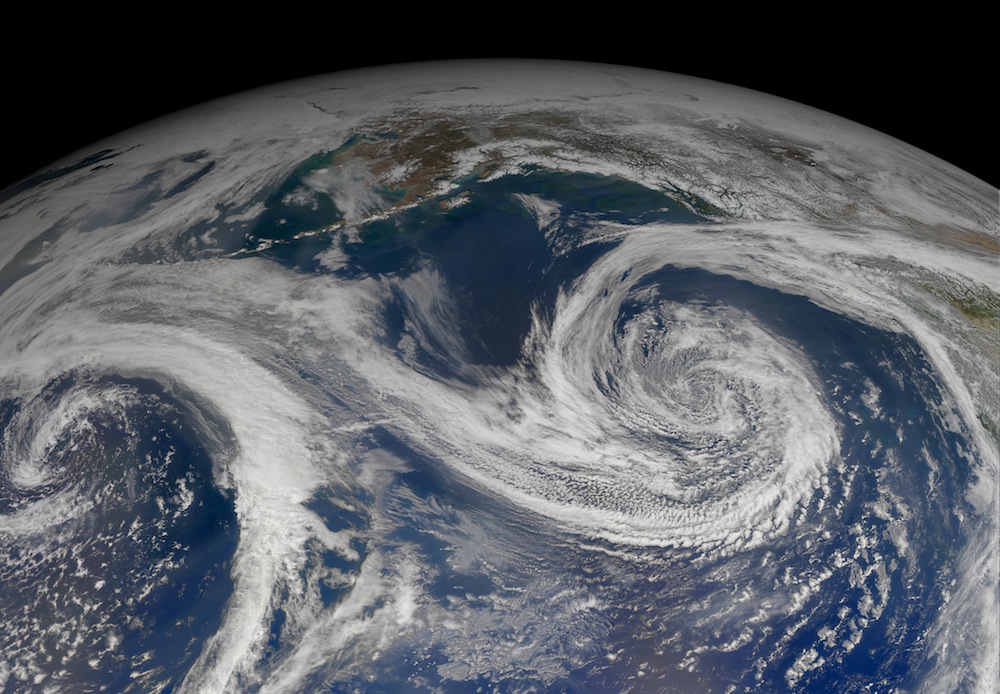

Beautiful swirling clouds make a striking first impression in a new satellite image of the southern Alaska coast. But look closer — another sort of beauty lurks beneath the surface.

Hugging the coastline, a green-blue mass of phytoplankton is blooming. In the satellite image, each individual phytoplankton is tiny and invisible to the naked eye. When spring sunlight shines on the waters of the Gulf of Alaska, however, these plantlike organisms flourish, blooming in such numbers that their internal chlorophyll (the same stuff that makes plants appear green) changes the color of the ocean.

This image is a composite made from pictures snapped by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Aqua satellite, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. The photograph date to May 2. A closer view from May 9 shows a more detailed look at a phytoplankton bloom near the Prince William Sound.

Phytoplankton are at the base of the ocean food chain. Like plants, they survive via photosynthesis, converting the light of the sun into energy. They're found all over the world (even under Arctic ice), particularly in nutrient-rich waters like the Gulf of Alaska.

Sediment brought in by rivers feeding into the gulf, as well as windblown volcanic ash and glacier-tilled dirt, help feed blooms like the one seen in the Gulf of Alaska. Climate change could alter the frequency of these blooms, recent research finds.

In a study led by Boston University researcher Richard Murray, scientists found that increases in iron — an important phytoplankton nutrient — in prehistoric sediments were linked with corresponding phytoplankton blooms. These findings have implications for climate change, because as some areas of the globe get hotter and dryer, more iron-rich soil is likely to blow into the oceans. These nutrient infusions could, in turn, boost the activity of phytoplankton. Because phytoplankton use carbon in photosynthesis, their increased numbers might result in less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere — good news for a warming planet. The findings still lack proof, but illustrate the importance of these tiny green organisms.

Editor's Note: If you have an amazing Earth or general science photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Jeanna Bryner at LSphotos@livescience.com.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus