Whole Lotta Shakin' Goin' On: Busy Stretch for Large Earthquakes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

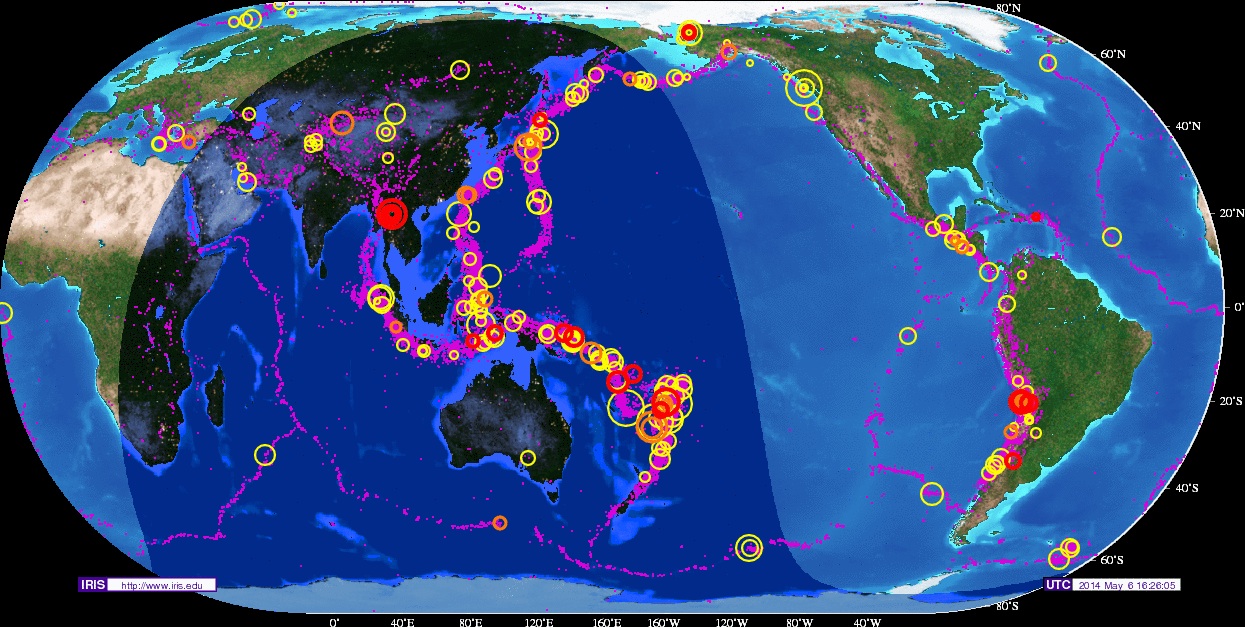

If you have gotten the sense that Earth has been active lately, you were right.

A Live Science analysis of U.S. Geological Survey data finds that April's first three weeks were the busiest stretch for earthquakes going back to at least the beginning of last year. The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center said April was a record month for warnings from the Alaska-based center.

How about May? There were 17 magnitude-6 or larger earthquakes globally between May 1 and May 20, following a busy April that saw 26 temblors in that same magnitude range. By comparison, there were only six earthquakes this big in February, eight in January and just two in December.

The average monthly tally of these large earthquakes in 2013 was 11.8. But experts say there's nothing unusual about the recent spike. And while April's pace was high, its monthly total is not a record. You only need to go back to March 2011 — when a magnitude-9.0 earthquake struck the Tohoku region of Japan — for a higher count: 72. [7 Craziest Ways Japan's Earthquake Affected Earth]

Are you wondering if it's your imagination, or is there really an uptick in earthquakes? To find out, Live Science posed this question to seismologists, the scientists who study the trembling Earth, at their annual meeting in Anchorage, Alaska, last month. Not surprisingly, some had pithy responses.

Age of megaquakes?

"I've been answering that question for 34 years," said a smiling John Ebel, a professor at Boston College in Massachusetts. Translation: Nothing to see here. Move along.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Thorne Lay, a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, thinks there's something interesting happening with the world's great earthquakes.

Between 1900 and 2004, the average yearly rate of quakes of magnitude 8 and larger was 0.65, Lay told Live Science. In the past 10 years, that rate jumped to 1.8 — an increase of almost a factor of 3, he said. But only the biggest quakes are becoming more frequent. There isn't a similar rise in smaller earthquakes. [The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

"There's a big mystery there," Lay said. Unfortunately, it's a tough one for researchers to solve. "The 110-year record is totally lacking," Lay said. "It's too short a window."

The short time window of instrumental records, since the first seismometers went into action, makes it hard to find patterns amid the statistical noise of earthquakes.

However, other seismologists have also analyzed the recent spate of great earthquakes and concluded it's totally random, according to several studies, including one published in the August 2012 Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

No end times here

Indeed, many, many statistical studies have shown that the Earth's shaking is a Poisson process, in which events occur completely randomly and independently of each other. That helps explain why earthquakes cluster in time — like flipping a coin and landing several heads in a row — or have surprisingly long quiet periods. So this year could be one in which those random clusters of earthquakes are occurring.

That's what Eric Fielding thinks. "There are more, but it's still within statistical variation," said Fielding, a geophysicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

And five months into 2014, the worldwide earthquake numbers do indeed track along with the long-term statistics kept by the U.S. Geological Survey.

Since 1900, every year has averaged around 15 magnitude-7 quakes, or about one every three weeks, and 134 magnitude-6 temblors, and so on, the USGS reports.

This year's recent major quakes included the magnitude-8.2 event in Chile on April 1 and the magnitude-7.2 quake in Mexico on April 18. Not on this list was the moderate 5.1-magnitude temblor in Los Angeles on March 29.

The USGS records about 20,000 earthquakes every year, but estimates that several million more go unmarked by people — mostly quakes too small to be felt.

However, even small earthquakes get more attention than they used to, thanks to the power of electronic media, said USGS scientist Paul Earle, director of the National Earthquake Information Center. A magnitude-4.8 temblor near Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming was once local news, but now the information quickly spreads worldwide among people who track shaking at the rumbling supervolcano.

Sorry, Sooner State

So are there more earthquakes this year? Maybe. Maybe not! It depends on whom you ask. Scientists don't even know why earthquakes start and stop, so there's a lot left to learn.

But there is one place where the answer is an unequivocal yes: rumbling, rattling Oklahoma.

The rise in earthquakes in Oklahoma is "unprecedented," in the words of state geologist Austin Holland. And unless you belong to the state oil and gas lobby, the cause is pretty clear — pumping million of barrels of chemical-laced fracking wastewater into deep wells.

So many small earthquakes struck Oklahoma in recent months that the USGS recently issued an earthquake hazard warning for a magnitude 5, which could damage buildings and structures.

Because of the recent jump in man-made earthquakes (called induced seismicity) throughout the United States, the USGS plans to estimate the national shaking risk from induced earthquakes for the first time, said USGS geophysicist Justin Rubinstein. The USGS issues 30-year forecasts of earthquake probability for the United States.

"The increased earthquake rate indicates there is an increase in earthquake hazard," Rubinstein said at the Anchorage meeting.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus

![The numbers of earthquakes recorded at various magnitudes. [See full infographic]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/tCYhUp3UXKzLKYZKZBSH5i.jpg)