Personhood for Pets? How the Human-Animal Bond Has Evolved

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Since humans first domesticated cats and dogs, these furry friends have taken on increasingly important roles in people's lives. Now, a growing movement aims to recognize Fido and Felix not just as pets, but also as legal citizens.

As wild animals, dogs and cats first entered human life in the role of hunting animals and guardians, then as companions and finally as family members. Now, a legal battle is underway that could make these animals fellow citizens.

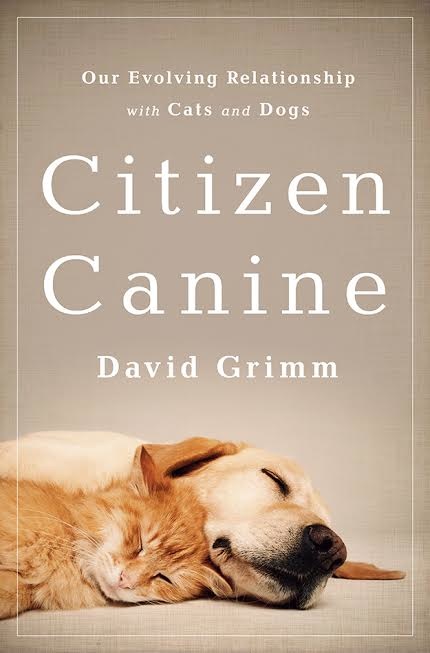

Author and science journalist David Grimm explores theses notions in his new book "Citizen Canine: Our Evolving Relationship with Cats and Dogs" (PublicAffairs, 2014).

"It's kind of remarkable when you think about how theoretically different these animals are from us," Grimm told Live Science. "Our last common ancestor with [dogs and cats] was probably more than 100 million years ago. Yet it's these two animals we've formed the closest association with."

From feral to family

The first potential evidence of dog domestication dates back to 30,000 B.C., in the form of a skull of a wolflike creature found in a cave in Belgium. Other evidence suggests dogs weren't domesticated until thousands of years later.

Evidence of cat domestication dates back to 7,500 B.C., when a feline was buried with a human in a Neolithic village on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Before they were pets, dogs helped humans hunt, and cats helped guard grain supplies by keeping rats and mice away, Grimm said. Eventually, people started to treat these animals more like pets.

But the Middle Ages were a grim period for cats and dogs. In A.D. 1233, Pope Gregory IX issued the "Vox in Rama," which suggested black cats were agents of Satan, prompting the massacre of tens of millions of cats throughout Europe. And, in 1637, French philosopher René Descartes declared animals were soulless machines, which paved the way for experiments on living dogs. [See Images of the Ancient Egyptian Cats]

It wasn't until the late 1800s and early 1900s that there was a rise in sentimentality toward dogs and cats, Grimm said. Flea-and-tick products appeared in the 1880s and kitty litter was invented in 1947, enabling people to bring cats and dogs indoors, where people treated them as family members.

"As human relationships are becoming more virtual, it's creating an emotional void in our lives," Grimm said. "Cats and dogs keep us anchored to the real world."

Meanwhile, the legal status of these animals has been playing catchup.

Journey to personhood

Today, there are animal anti-cruelty laws in all 50 U.S. states, with penalties that include fines or prison time. Custody battles have been waged over family pets, and emotional-distress damages have been awarded for harm to a pet. Dogs and cats can even inherit money, Grimm said. But they're still considered property, "no different from a toaster in the eyes of the law," he said.

Now, a growing effort seeks to grant personhood to animals, including cats and dogs. Driving this movement is an increasing awareness of animal intelligence and their emotional capabilities.

Research on the canine mind has exploded in recent years, Grimm said. Dogs can understand pointing, an ability that chimpanzees lack, and research also suggests dogs are capable of empathy, and perhaps even abstract thought.

Cats are much harder to study, because as any cat owner knows, it's tough to get a cat to do what it's told. However, cats are known to be intelligent creatures too, Grimm said.

Yet not everyone supports the push to treat animals as fellow citizens.

Veterinarians worry about malpractice lawsuits, which could become even more costly if animals were granted personhood. Scientists worry that recognizing pets as legal persons could make it impossible to use animals in research, where they are used for basic science and for testing clinical treatments. Farmers are also concerned that if dogs and cats were considered "people," cows and chickens could be next — a move that could put an end to the livestock industry. Society will continue to grapple with these issues moving forward, Grimm said.

On a personal level, Grimm, a cat owner himself, marveled at how much humans' relationship with cats and dogs has changed over time. "Ten thousand years ago, [a cat] was a wild animal that would rip your face off if you got too close," he said. "Now, it's purring in your lap."

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 9:13 a.m. ET May 13, 2014 to include the full title of Grimm's book.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus