Where's the Best Place to Feel an Earthquake?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Italy, the renowned land of lovers, reports that the best place to feel the earth shake is … in bed.

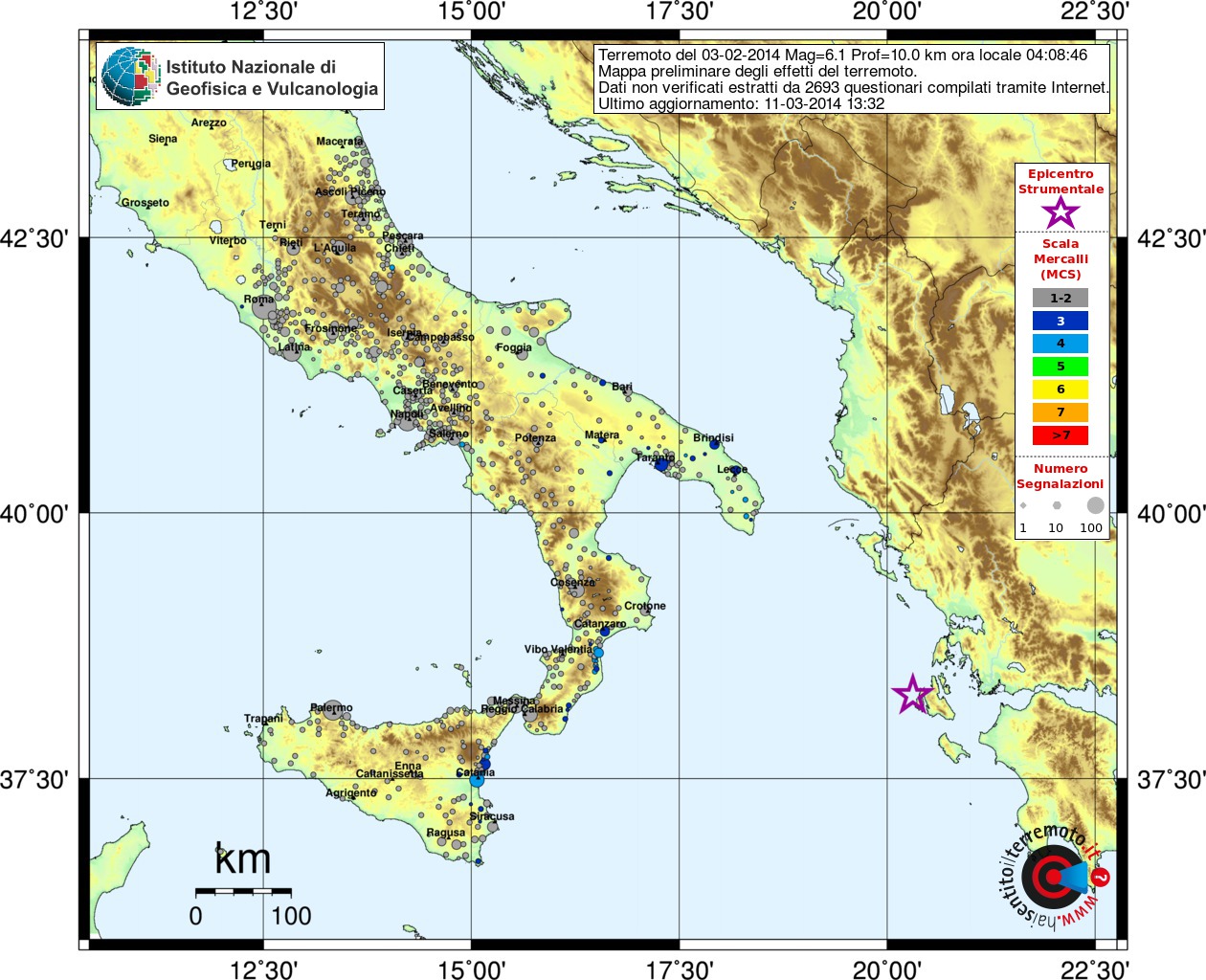

Earthquakes frequently rattle Italy, a country crushed between the African and Eurasian tectonic plates. When Italians feel a "terremoto," they can describe the sensation at a website run by the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, or INGV) in Rome. The online form quizzes people on what they felt, their location and what they were doing during the earthquake. The questionnaire is similar to the U.S. Geological Survey's "Did You Feel It?" website, which collects earthquake reports from people around the world.

What earthquake?

With more than 600,000 reports, the INGV database offers valuable insight into how people perceive earthquakes. When it comes to sensing the smallest earthquakes, it turns out that what people are doing is more important than their location, according to Paola Sbarra, a researcher at INGV in Rome.

Sbarra and her colleagues analyzed about 250,000 earthquake reports to see how people's perceptions of low to moderate earthquakes compared to the measurements recorded by seismic instruments. The researchers looked at earthquakes with a local magnitude between 3 and 5.9. The results were published in the March issue of the journal Seismological Research Letters. [Video: Earthquake Magnitude Explained]

Someone at rest, especially if they were awake and in bed, was more likely to feel an earthquake than someone in motion, the researchers found. Next up in importance was building height: People on higher stories felt earthquake shaking more intensely than those on lower stories.

"We were surprised to discover that the situation variable — at rest, in motion, sleeping — has more weight than location," Sbarra said. Currently, the European earthquake intensity scale places more weight on self-reports of location, rather than activity. The intensity, which scales from 1 to 12, describes how people experience an earthquake. For example, the number of people who report feeling an earthquake of intensity 5 (considered strong) is important because engineers and insurers plot potential losses and damage based on this intensity.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The results confirm what housemates have long known: Everyone in the same room may not sense the jerk and slap of a small earthquake. Someone sitting on the sofa may detect the rumble of passing seismic waves, while someone walking down the hall or doing dishes could miss the slight jiggle entirely.

"What you are doing affects [your] perceptions of an earthquake more than where you are at," Sbarra told Live Science. "The best perception of earthquake shaking is obtained at rest. People in motion outdoors have the worst perception."

Quake crowdsourcing

Researchers in the United States have also dissected the USGS database for insights into everything from differences between the East and West Coast shaking to perceptions of earthquake risk, said David Wald, a USGS geophysicist in Golden, Colo., who created the "Did You Feel It?" system.

For example, a 2005 study published in Earthquake Spectra found that people overestimate their earthquake experience, a phenomenon called cognitive anchoring. This is akin to someone in Sacramento, Calif., boasting that "I survived the big quake of 1989" — when the damage was actually concentrated in Loma Prieta and San Francisco, about 80 miles (130 kilometers) to the west. "They have a bias that they can handle anything because they lived though a big earthquake," Wald said.

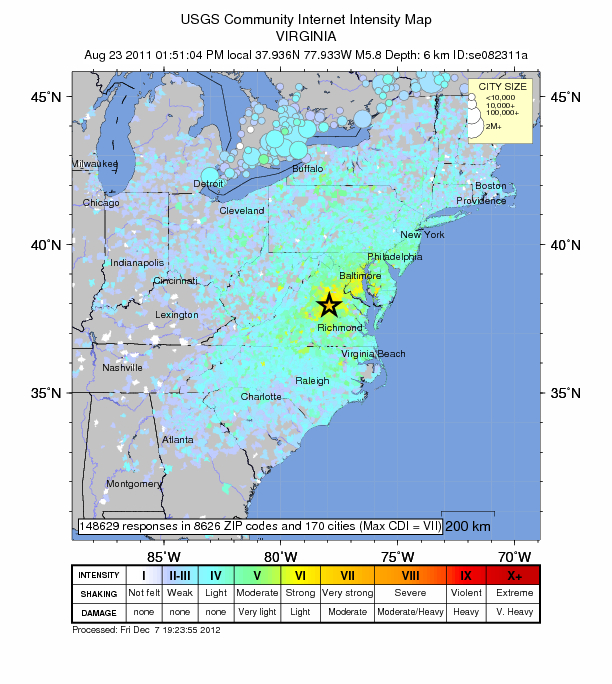

The USGS has collected about 2.5 million reports via the "Did You Feel It?" website, Wald said. The reports clearly illustrate that earthquake shaking is more widely felt in the East than in the West, he told Live Science. That's because the crust is older and less broken up by faults than in the West, so seismic waves from an earthquake can travel farther.

After the 2011 Virginia earthquake, the site also helped emergency responders figure out where to find the worst damage. The 148,000 "Did You Feel It?" reports from that event meant the USGS knew exactly where the strongest shaking hit, even though the agency had few seismometers on the ground. That meant the agency could help emergency officials quickly direct their response to the hardest hit locations.

"The citizen science aspect of this has been pretty amazing," Wald said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus