New European Earthquake Catalog Offers Clues to Future Risks

Earthquakes in Europe have influenced everything from its legends to its languages.

According to Greek mythology, the Oracle at Delphi spoke through women who inhaled delirium-causing vapors; now, modern geologists say these vapors were hydrocarbon gases released along earthquake faults and fractures crisscrossing the site of the Delphi temple.

In Italy, a magnitude-6.7 quake in 1638 permanently tweaked the Calabria region's dialects, according to a study published in the journal Annali di Geofisica in 1995. For example, the town of Savelli, founded after the quake, was linguistically isolated from its neighbors because it was settled by refugees from villages far to the west.

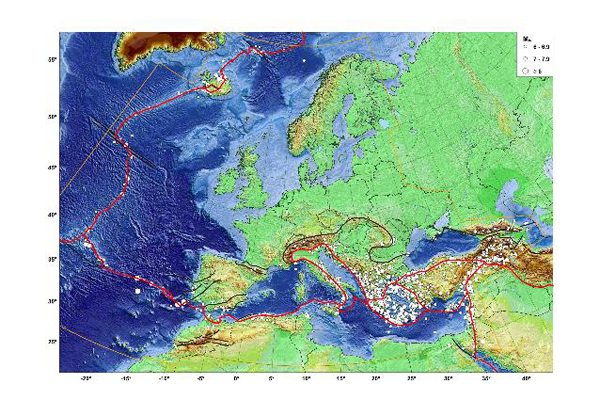

About 45,000 earthquakes large enough to feel have rocked the continent in the past 1,000 years, according to a newly updated catalog of earthquakes in Europe and the Mediterranean. Combining this historic information with modern-day geologic investigations is the first step in forecasting Europe's future risk of earthquakes, researchers say. [Stunning Map Reveals World's Earthquakes Since 1898]

"One has to bring together the information from very old times, and from very modern times," said Gottfried Grünthal, of the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam, Germany.

Estimating earthquake risk requires "good knowledge about the seismological past. That means we have to extend our knowledge of the seismicity of an area as long into the past as possible," Grünthal said.

The new catalog reveals that most of Europe's seismicity is concentrated along plate boundaries in the Mediterranean, including the present-day countries of Italy, Greece and Turkey, along with regions in southern Iberia, the Balkans and the Caucasus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But earthquake risk is also found in more northerly locations, such as along the stupendous mountain-building faults of the Alps. One of Europe's largest and most devastating quakes of the past millennium was actually in Switzerland. The Basel earthquake, which struck on Oct. 18, 1356, with a magnitude 6.6, destroyed the town and toppled buildings in Germany and France.

Scientists pinpointed the fault responsible in 2001, and concluded the next temblor there could occur in about 1,500 to 2,500 years.

Building the catalog required Grünthal and colleague Rutger Wahlström to act as both historians and seismologists. In central Europe, they collaborated with historians at the University of Potsdam to estimate the size of past earthquakes in Germany. For other regions, Grünthal relied on countries' own earthquake catalogs – 80 in total. The researchers also examined more than 100 studies and performed their own analyses of key historical earthquakes.

The bulk of the work involved standardizing the earthquake records to the modern "moment magnitude" scale, to ensure that a quake in 17th-century Germany could be compared to a quake in 16th-century Italy. The moment magnitude scale provides estimates of the total energy released during earthquakes, and replaced the Richter scale in the early 1980s.

Magnitude is also a key part of the equations that predict ground motion, or shaking, which engineers and architects rely on to design earthquake-safe bridges and buildings.

With each country's records brought up-to-date, researchers around the world can now use the catalog when assessing Europe's risk of future quakes. "Having a standardized earthquake catalog is the first step in developing a seismic hazard assessment," Grünthal said.

A report describing the work appears in the July issue of the Journal of Seismology.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus