Ocean's Biggest Current Carries More Water Than Thought

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

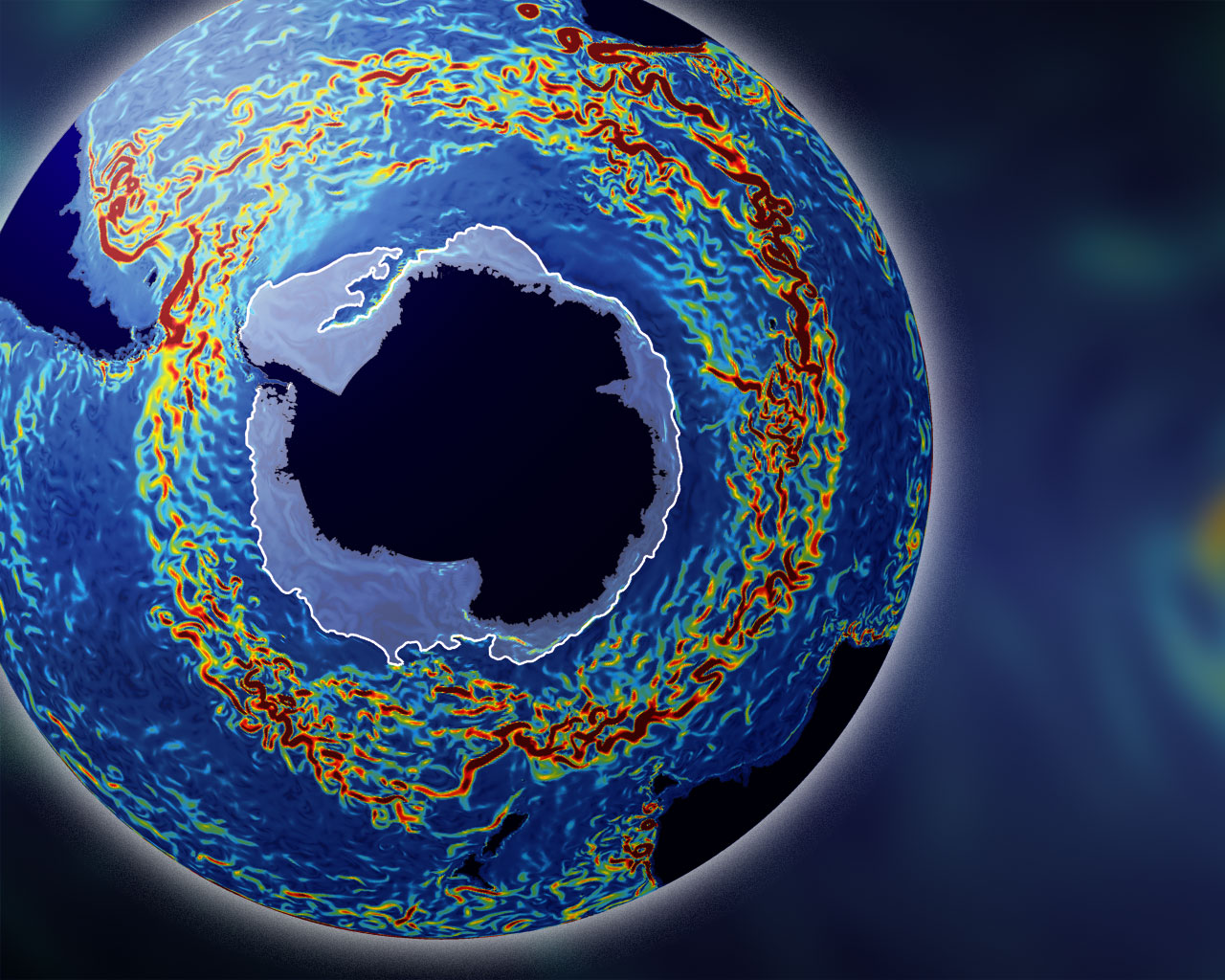

The world's biggest wind-driven ocean current carries 20 percent more water than previously thought, scientists announced this week.

A team of oceanographers reported the results of four years of continuously monitoring the Antarctic Circumpolar Current on Monday (Feb. 24) at the 2014 Ocean Sciences Meeting of the American Geophysical Union in Honolulu. The Circumpolar Current circles Antarctica clockwise from west to east, speeding ships flowing with the current but providing resistance for those sailing in the opposite direction. The churning waters ferry heat, salt and marine life between the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans, but the current also isolates Antarctica from warmer waters to the north.

Because the Circumpolar Current plays an important role in moving heat around the planet, scientists are keen to better understand how the rotating flow may respond to climate change. For example, the wind-driven current could increase due to changing wind conditions around Antarctica. The band of westerly winds that drive the Circumpolar Current have both sped up and shifted southward in the past 60 years.

"We want to know how the current will respond to changing conditions, so quantifying the transport gives important guidance to the climate models that are trying to predict the future," Kathleen Donahue, a principal investigator on the project and an oceanographer at the University of Rhode Island (URI), said in a statement.

A more accurate measurement of how much water flows with the current will help improve climate and ocean models, Donahue said.

In 2007, Donahue and her colleagues braved the notoriously harsh weather in the Drake Passage and deployed ocean monitors that remotely transmit data on everything from the current's water temperature and pressure to eddy patterns. The Drake Passage is the narrow chokepoint between South America and Antarctica. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

"We're never going to be able to measure the whole ocean," Randolph Watts, a URI oceanographer and co-investigator on the project, said in the statement. "So if we're going to make accurate predictions of future climate, we're going to have to accurately measure processes like water transport and heat flux at key locations like the Drake Passage to guide our understanding."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The research team also discovered the Circumpolar Current's speed, which can reach more than 1 mph (1.6 km/h), also stays strong all the way to the seafloor, they reported at the meeting. The current extends from the sea surface to depths of more than 13,000 feet (4,000 meters).

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus