Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

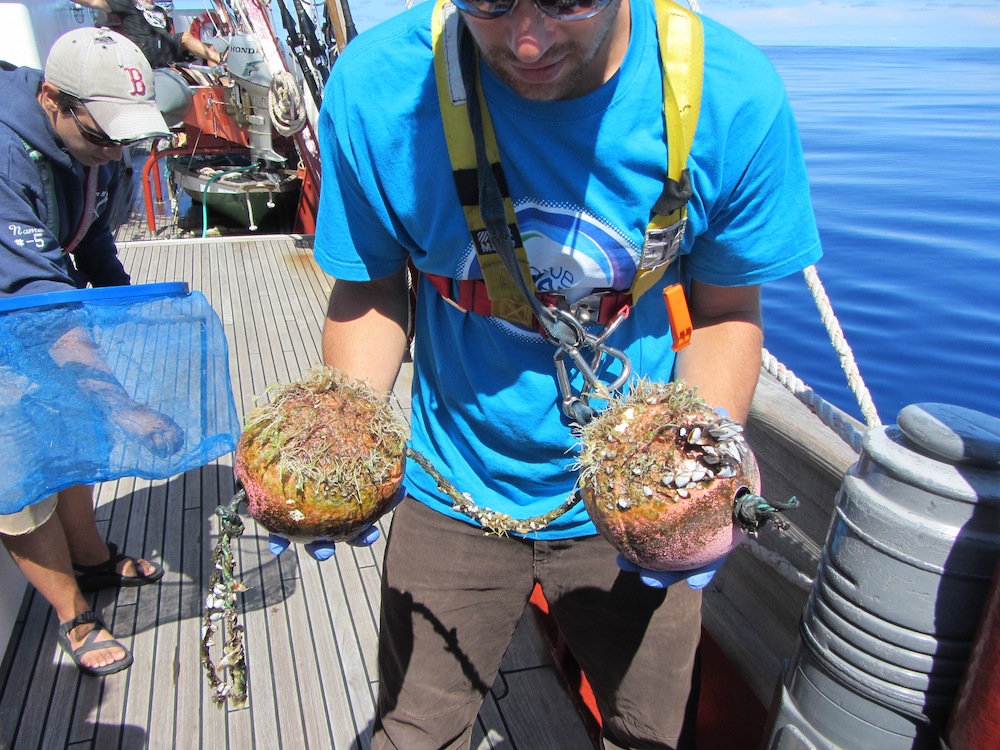

There's a secret world of microbes hidden on the plastic littering the oceans, and scientists are untangling how these mysterious microbial communities, dubbed the "plastisphere," are impacting the ocean ecosystem.

The ocean is teeming with trash, which collects in places in the ocean where currents can trap the debris, such as the great Pacific garbage patch, which is about the size of Texas. Researchers have found that seabirds often ingest this debris, but little was known about how sea debris affected the entire ocean ecosystem.

Last year, scientists discovered that about 1,000 microbes thrived on the plastic debris drifting in the oceans. Many of the bacteria belong to the genus Vibrio (the same genus as the cholera bacteria), which is known to cause diseases in humans and animals. Other microbial members of the plastisphere seemed to hasten the breakdown of the plastic. The microbes also look markedly different from ordinary marine microbes, the scientists said.

But the researchers didn't understand exactly how those microbes got on the plastic, or whether they were affecting the ocean ecology.

In follow-up research, scientists have found evidence that these microbes can form colonies on plastic in just a few minutes. In addition, some types of harmful bacteria tend to prefer living on plastic more than others do. [In Photos: Trash Litters Deep Seafloor]

As a follow-up, the researchers are trying to see whether fish ingesting the plastic could help these bizarre microbes thrive, by providing additional nutrients for the bacteria in their guts.

Unlocking the mysterious world of these microbes could help scientists understand the role of plastic in the ocean as a whole.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"One of the benefits of understanding the plastisphere right now and how it interacts with biota in general, is that we are better able to inform materials scientists on how to make better materials and, if they do get out to sea, have the lowest impact possible,” Tracy Mincer, an associate scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Woods Hole, Mass., said in a statement, referring to how the plastisphere interacts with other life in the oceans.

The findings were presented yesterday (Feb. 24) at the 2014 Ocean Sciences Meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus