A Century of Museum Records Reveal Species' Changing Lives (Op-Ed)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

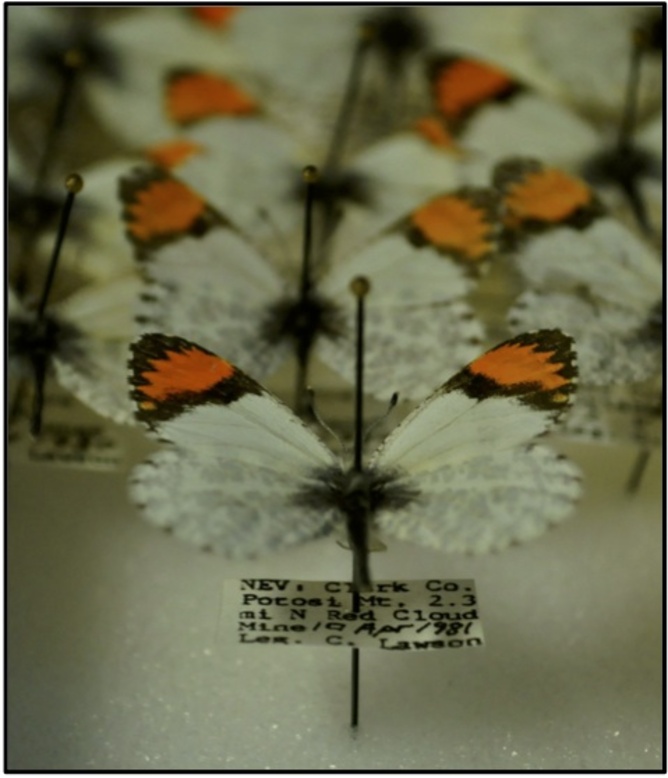

Natural history museum records are most often associated with preserved specimens, kept with information about the place and time of collection. From these we can generate a record of a species' geographical distribution, and indicators of its life-cycle timing – events such as the flowering of plants, bears rising from hibernation, or butterflies pupating and flying for the first time.

Museums hold hundreds of thousands of specimens and observations collected around the world for centuries – even in places that lack other conventional, modern record-keeping. We can use museum collection records as a window into the past, into areas that are not as well studied. This approach is especially useful for understanding how biodiversity is responding to climate change.

A team including myself at the University of British Columbia and colleagues at the University of Ottawa and the Université de Sherbrooke in Canada recently published a paper in the journal Global Change Biology that used museum records.

We found that the timing of butterflies' flight season is sensitive to spring temperature. Climate change has led spring to begin earlier in many parts of the world, and this has brought forward many butterflies' species flight seasons too.

We took advantage of the efforts made back in 1998 to digitise Canadian butterfly collection records. Our analysis paired around 48,000 unique observations from across Canada between 1871-2010 with weather station data to examine the sensitivity of flight season timing of 204 butterfly species to spring temperatures. To our knowledge, this is the first study to do so.

Butterflies work well as indicators for how climate change is affecting wildlife since their physiology and behaviour is so sensitive to the environment around them. This means they act as an early signal for other species.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

We found with each degree of warming, butterflies took flight 2.4 days earlier. For most species this means an average shift of 0.2 days per decade over the past hundred years, but this average hides the wide disparity of temperature changes and species responses across Canada. Given that temperatures are expected to continue rising, this shift will only get bigger.

This sensitivity to temperature can be used to predict species’ vulnerability to climate change. For example, highly sensitive species that start their flight season too early could be more likely to be killed by stressful weather such as frost. Or it may mean that they become active before their host plants have flowered that season and are ready for them, meaning they’d starve.

We also found we could predict which species are likely to be more sensitive than others. This is valuable information for those species where historical data is patchy. We particularly found species with earlier flight seasons, that is, spring fliers not summer fliers, and those that can fly longer distances are likely to more more sensitive to change than others.

This shows how helpful museum collections can be in understanding how climate change has influenced species life-cycles. Herbarium (plant) records have similarly revealed how flowering times in plants have responded to warming, but few have considered records for animals. Given the massive number of museum collection records available around the world, this represents a very under-used resource.

Unfortunately, as science budgets are slashed the funding for compiling, digitising and housing these records disappears. For example, most of the butterfly specimens at the University of British Columbia’s Beaty Biodiversity Museum have not been assembled and organised and couldn’t be included in this study. Instead, I had to rely on private collections in British Columbia.

Fortunately, there are initiatives such as Canadensys and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility that are working to make this data accessible to everyone. This work reinforces the value of museum collections and the efforts to archive and appreciate our natural history.

Heather Kharouba does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus