Editor's note: By the end of this century, Earth may be home to 11 billion people, the United Nations has estimated, earlier than previously expected. As part of a week-long series, LiveScience is exploring what reaching this population milestone might mean for our planet, from our ability to feed that many people to our impact on the other species that call Earth home to our efforts to land on other planets. Check back here each day for the next installment.

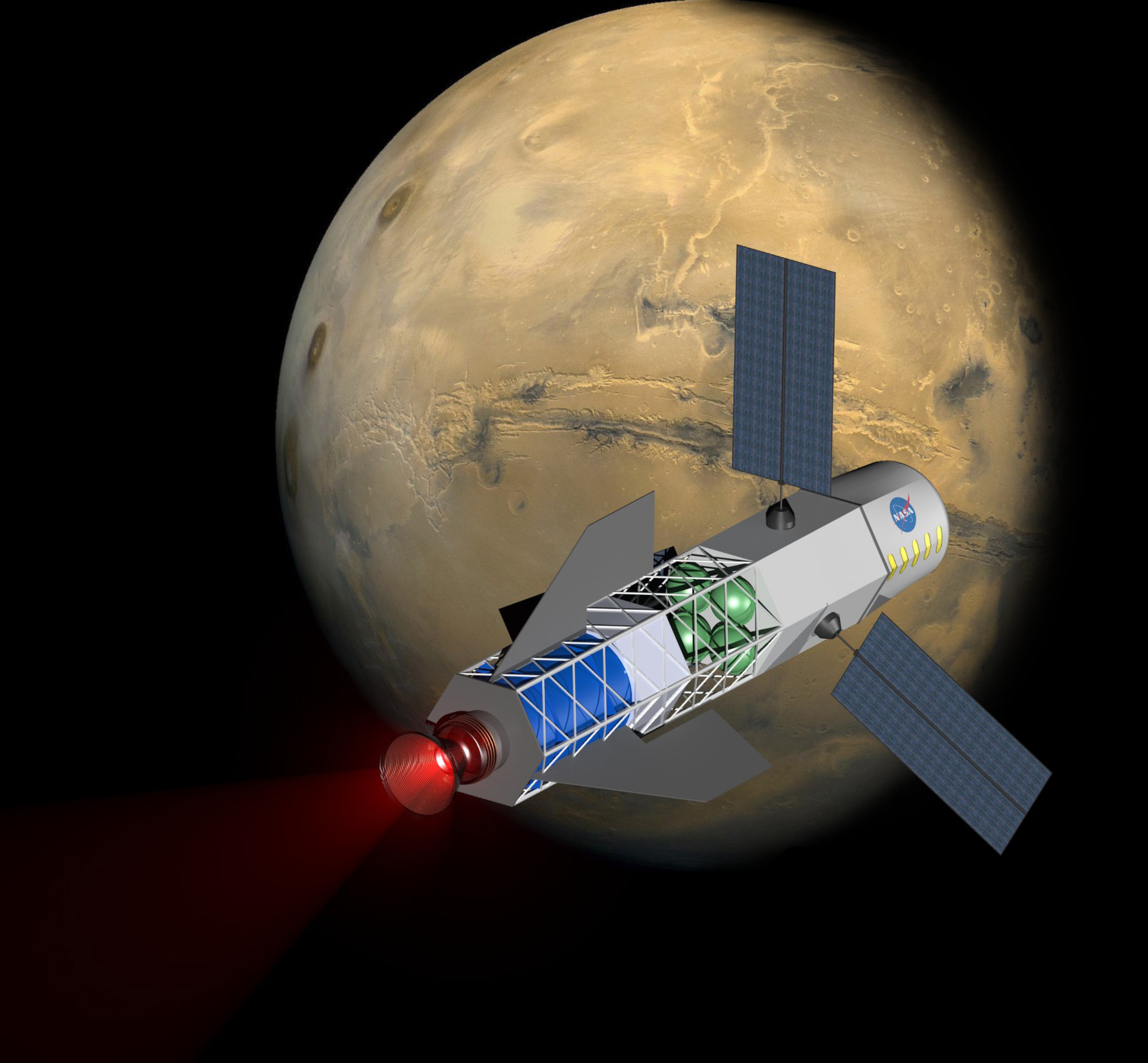

Robert Zubrin wants humanity to put down roots on Mars, and he thinks he knows how to make it happen at a reasonable price.

The key is to travel light and live off the land, accessing the plentiful resources available in the Red Planet's dirt and air, says Zubrin, president and founder of the nonprofit Mars Society, which advocates manned exploration of the Red Planet. For example, pioneers could generate oxygen and rocket fuel by pulling feedstock out of the thin Martian atmosphere, and they could get all the water they need from the soil under their boots.

That Martian dirt is also rich in iron oxide and silicon oxide, so explorers could make their own iron, steel and glass. They could manufacture plastics, too, using soil water and carbon dioxide, which dominates the Red Planet's atmosphere.

Becoming as self-sufficent as possible is the ultimate goal, so that the continued existence of the outpost does not rely on frequent (and expensive) resupply trips from Earth.

Whenever the first manned outpost springs up on the Red Planet, its solitary existence on a previously virgin world will inspire a lot of soul-searching here on our increasingly crowded Earth.

And in an interesting twist, the more crowded our planet gets, the more likely we may be to start setting up shop on Mars and other locations beyond Earth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The number of people who call Earth home is slated to jump from the current 7.1 billion to potentially 11 billion by the end of the century, according to a recent United Nations report that used a more sophisticated statistical analysis than previous reports and that upped the expected population rise by the end of the century. This boom could accelerate the pace of climate change, strain the availability of key resources such as fresh water and threaten biodiversity around the globe, experts say.

But the ongoing population rise may have an impact beyond Earth as well, making humanity more able and more willing to leave our home planet and begin settling the solar system, according to Zubrin.

"Technology is going to advance, the wealth of society is going to increase and the number of people is going to increase, which means the number of outliers is going to increase — the number of people who think differently," Zubrin told LiveScience. [What 11 Billion People Means for the Planet]

"Most billionaires are going to continue to donate to the opera," he added. "But since there are going to be more of them, there's a greater probability that some of them are going to say, 'What I want to do with my life is open space to humanity.'"

Increased wealth and knowledge

The field of private spaceflight is beginning to take off now, thanks in no small part to the efforts of a few extremely wealthy individuals with big space dreams — billionaires like Elon Musk (founder of SpaceX), Sir Richard Branson (Virgin Galactic), Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin) and Paul Allen (Stratolaunch Systems).

SpaceX has already made history by becoming the first private company to make cargo deliveries to the International Space Station, and Musk has bigger dreams for the firm. He has said he founded SpaceX primarily to help humanity become a multiplanet species, and late last year the entrepeneur laid out his vision for establishing a Mars colony that could support perhaps 80,000 people. [Red Planet or Bust: 5 Manned Mars Mission Ideas]

The burgeoning global population should help humanity achieve such ambitious goals, Zubrin said. For one thing, there will be more rich space enthusiasts like Musk willing to help initiate or bankroll manned exploration efforts — perhaps many more by 2100, if per capita income continues to rise as population increases, as occurred throughout the 20th century.

A higher population will also help humanity acquire the knowledge and skills needed to explore and settle a world such as Mars, Zubrin added.

"Inventions are cumulative," he said. "The technological base is going to be expanding at an accelerating rate, because there are going to be more people contributing inventions."

But such reasoning only applies up to a point, before Earth is too jam-packed with people, other experts say.

"Getting into space means you have to have a basic infrastructure, and if the Earth's population gets so enormous that we're all reduced to poverty, we won't be able to afford to move into space," award-winning sci-fi author Ben Bova told LiveScience. "There's an old saying in Washington: 'I'm so busy doing what's urgent, I can't do what's important.'"

The riches of space

If the march toward 11 billion does indeed help push humanity off the planet, then population growth may have some self-correcting potential. Expanding our species' footprint out into the solar system could help deal with the boom and perhaps even slow it down, Bova said.

"As population continues to grow, we are going to need more and more natural resources to support that population," said Bova, whose "Grand Tour" novel series explores this issue in depth. "And we have seen in space natural resources in larger amounts than the whole Earth can provide."

One of those resources is energy, Bova said. By looking up and out, humanity could generate huge amounts of power while simultaneously reducing or even ending its dependence on fossil fuels, which contribute to climate change by spewing heat-trapping carbon dioxide into Earth's atmosphere.

"The Earth intercepts less than 1 percent of the amount of energy that the sun is beaming out," Bova said. "We can build solar power satellites and greatly increase the amount of energy available to the human race."

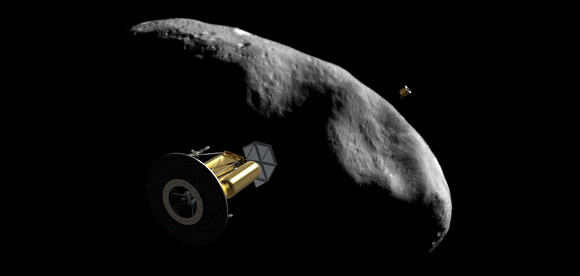

The moon and asteroids are also packed with riches. For example, some space rocks contain large amounts of platinum-group metals — platinum, ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium and iridium — which are key components of virtually all electronic devices.

The platinum-group elements represent "one opportunity to get a material in space that could be of great benefit back here on Earth," said Chris Lewicki, president of the billionaire-backed asteroid-mining firm Planetary Resources. [How Asteroid Mining Could Work (Infographic)]

The enormous wealth created by extracting such resources could help put the brakes on our species' exponential growth, Bova said.

"My reading of history is that the best way to reduce population growth is to make people richer; rich people don't have as many children as poor people," he said. (Indeed, social scientists have found that fecundity tends to drop as per capita income rises, both within a society and across different countries.)

A relatively small number of people working in space, Bova added, "can return the resources needed to support a huge population and make it wealthy enough so that the population growth slows down."

Changing hearts and minds

Bova doesn't see the colonization of other worlds such as Mars as a viable safety valve for an overcrowded Earth, though, saying that it would be impractical to ship enough people off the planet to make an appreciable dent in the global population anytime soon.

However, that doesn't mean that off-world settlement can't lighten humanity's footprint on Earth, others say.

"Colonizing Mars will have a positive effect on achieving a sustainable human population on Earth because of the impact that it will have on Earth, not because of the number of Mars migrants," said Bas Lansdorp, CEO and co-founder of the Netherlands-based nonprofit Mars One, which aims to land four people on the Red Planet in 2023 as the vanguard of a permanent human settlement.

This plan is quite bold, as NASA — the world's premier space agency — is hoping to get people to the vicinity of Mars by the mid-2030s.

"Having humanity experience setting foot on another planet will make people aware that the Earth is our spaceship and that we need to treat it well," Lansdorp told LiveScience via email. "This happened because of the moon landings too, but the effect will be larger when it concerns colonization instead of a visit, and because of the larger reach of video images in 2023 as compared to 1969."

The rise of the space tourism industry — which will likely be aided by population growth, since more people should be able to afford flights to space — could have similar effects, helping more and more people see Earth as it really is: a tiny outpost of life, alone and adrift in the vast blackness of space, experts say.

"Those of us who have had the luxury of having had that view — I think you become a better steward of your own planet," said Commercial Spaceflight Federation president Michael Lopez-Alegria, a former NASA astronaut with four space missions under his belt.

"So the more people who are part of that club, so to speak, I think the better for us all," Lopez-Alegria told LiveScience.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.