Statins Do Not Harm Memory, Study Says

Statins, a group of drugs that treat high cholesterol, do not appear to impair people's memory, as some recent claims had suggested, and their long-term use may even protect against dementia, a new review of studies suggests.

The researchers looked at previous studies of statins and their effects on cognition. Eight studies included people who took statins for a short time, and together, the results showed no difference in users' performance on memory-related tasks compared with the performance of people who didn't use statins.

Another eight studies, including more than 23,000 people, examined the risk of developing dementia in people who were on statins for a longer time — between three and 25 years. Three studies found no link between statin use and dementia, and five studies found a lower rate of dementia in people who used statins.

Together, the results suggest that statin users have a 29 percent reduction in the risk of developing dementia, the researchers said.

"Generally, the message to patients and doctors is a reassuring one," said study researcher Dr. Seth Martin, a cardiovascular disease researcher at John Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Heart Disease. [10 Ways to Keep Your Mind Sharp]

Statins are some of the most prescribed drugs in the world, and are the first-choice drug treatment to prevent heart disease and stroke for people at high risk for these conditions, as well as for those who have been diagnosed with heart disease following a heart attack or stroke.

About one-quarter of U.S. adults ages 40 to 74 have high cholesterol and report using cholesterol-lowering medication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's report for recent years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In February 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued changes to statins' labels, warning that memory problems could be a possible side effect of the drugs, after some statin users reported cognitive impairment, forgetfulness and confusion.

Although the agency maintained that the labels should not scare people off statins, which have proved valuable in preventing heart disease, the label change led some experts to discourage the use of statins for people who have elevated cholesterol but who are not diagnosed with heart disease. Patients, too, started expressing concerns in talking to their doctors, the researchers said.

"We saw a lot of scared people in the clinic," Martin said. "We had people coming in, thinking that it may be lowering their IQ, or that [statins were] clearly the reason for their confusion when there were other potential reasons," such as interactions with other medicines people are taking, he added.

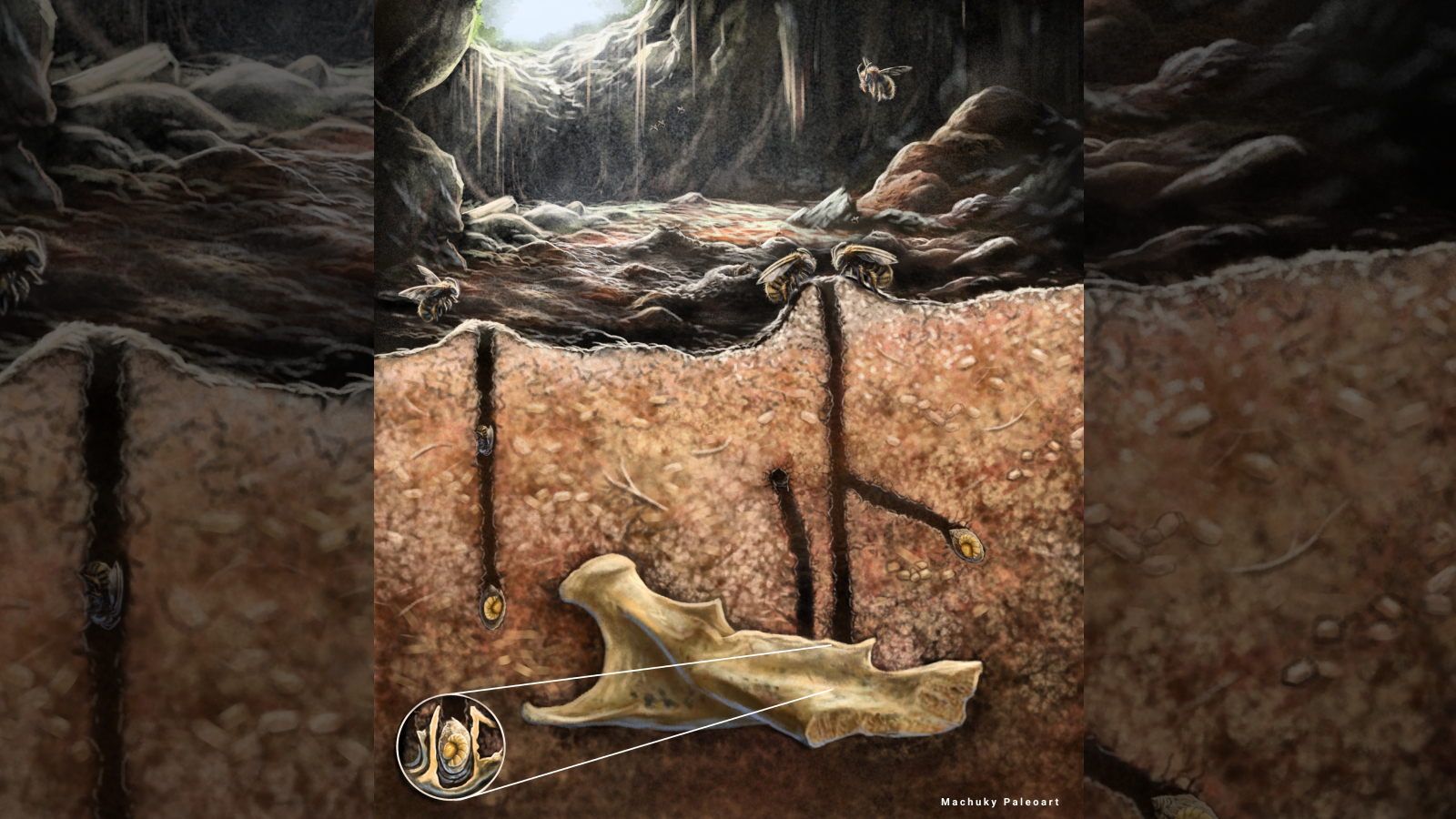

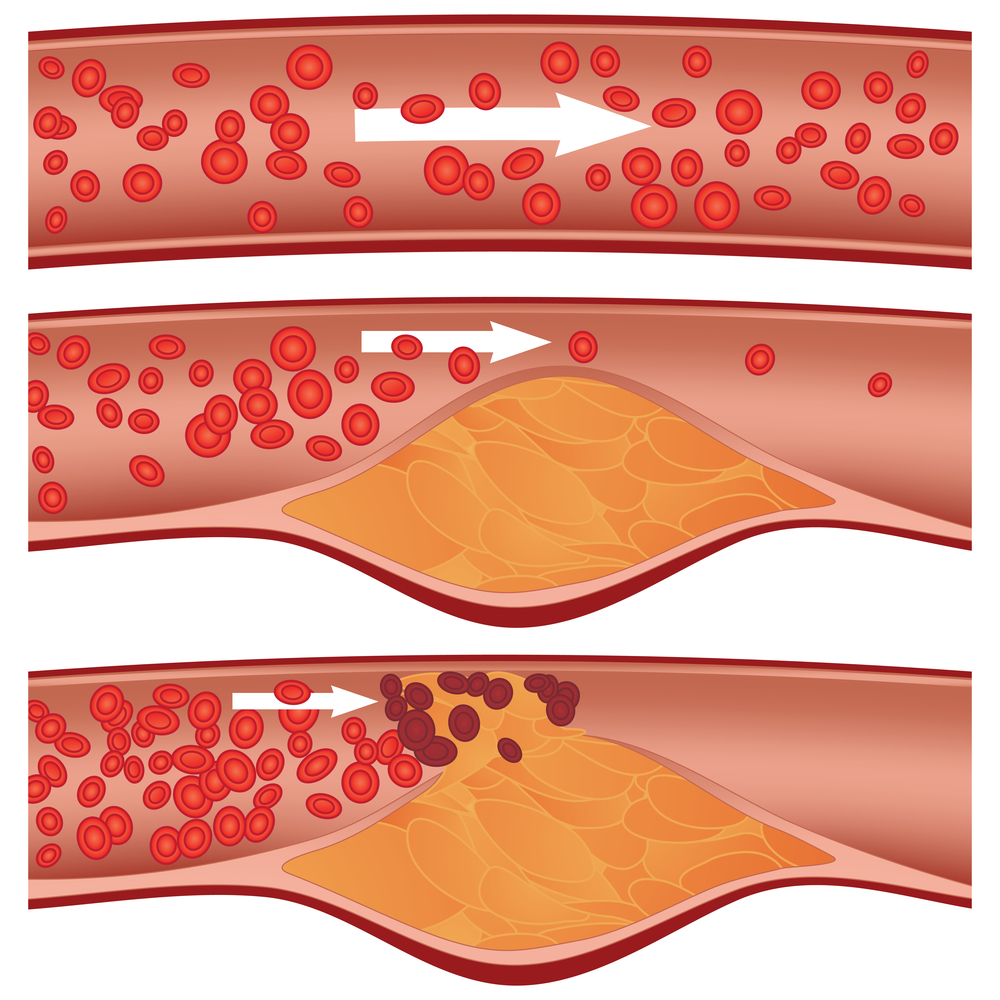

Statins work by reducing cholesterol levels in the blood, particularly low-density lipoprotein (LDL), which is known as the "bad" form of cholesterol that can build up as plaque inside blood vessels.

"It makes sense that over the long term, statins could protect against vascular dementia that could be caused by plaque buildup in brain vessels," Martin said.

It remains possible that a small minority of people do experience adverse memory side effects when taking statins, perhaps because of their genetics, but more research is needed to know whether this is true. However, for people who experience side-effects, researchers recommend trying lower doses, or switching from one statin to another.

"My suggestion would be not to jump to conclusions that statins are the culprit" for the memory problems the patient is experiencing, Martin said.

The study is published today (Oct. 1) in the journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.