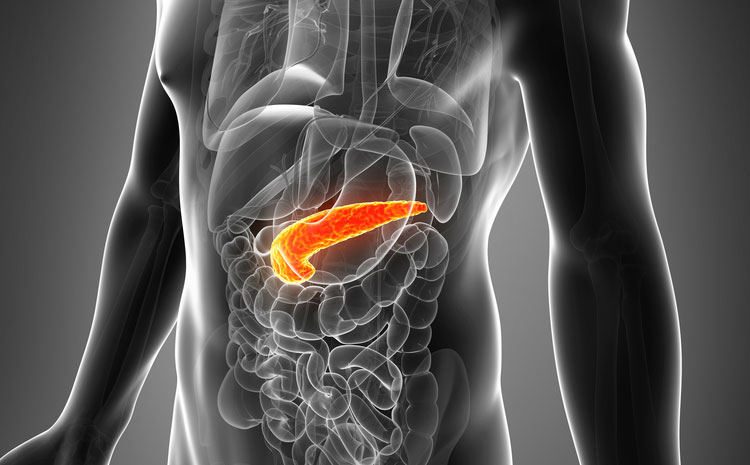

Pancreatic Cancer: Bacteria May Play a Role

Bacterial infections may play a role in triggering pancreatic cancer, according to recent research.

A growing number of studies suggest a role for infections —primarily of the stomach and gums — in pancreatic cancer. The disease is a particularly deadly cancer, which the American Cancer Society estimates will kill nearly 38,500 Americans in 2013.

"Pancreatic cancer is the worst form of cancer that people can have," said Dr. Wasif Saif, director of the gastrointestinal oncology program at Tufts Medical Center in Boston.

"It's the cancer with the highest mortality rate – 96 percent mortality," he said.

Although pancreatic cancer is extremely fatal, researchers don't really know its main causes, Saif said. The known major risk factors account for less than 40 percent of all cases.

Known risk factors for the disease include tobacco smoking, obesity, Type 2 diabetes, alcoholism and chronic pancreatitis, which is inflammation of the pancreas.

"The major finding of this research is the possibility that bacterial infection may be leading to pancreatic cancer," said Saif, who was not involved in the study. [Why Is Pancreatic Cancer So Deadly?]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings were published online July 10 in the journal Carcinogenesis, and they were authored by Dominique Michaud, a professor of epidemiology at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

Infections linked to cancer

According to the study, two bacterial infections in particular have been strongly linked to pancreatic cancer in the scientific literature.

Data suggest that people who have been infected with Helicobacter pylori, a bacteria that is linked with stomach cancer and peptic ulcers, and Porphyrmomonas gingivalis, an infection involved in gum disease and poor dental hygiene, may be more prone to developing pancreatic cancer.

Several theories aim to explain why these infections may be contributing to the progression of pancreatic cancer, Saif said. One is that the infections cause bodywide inflammation, which is known to play a role in pancreatic cancer.

A second possible mechanism is that these bacterial infections lead to changes in the immune system. When the immune system is weakened or altered by infection, it doesn't work as well to defend the body against cancer.

What's more, risk factors for pancreatic cancer, such as smoking, obesity and diabetes, may further suppress immune response, opening the door to opportunistic infections, according to the study.

Other theories proposed in the paper are that these bacterial infections may directly activate pancreatic tumor signaling pathways, such as those that promote the growth of new blood cells that feed a tumor. Another possibility is that infections indirectly activate pancreatic cancer pathways that trigger an immune response in the environment surrounding the cancer, but not in the tumor itself.

Practical implications

The idea that some bacterial infections can lead to certain cancers is not a new concept, Saif said. Researchers have been looking into this connection over the last decade, and have seen evidence of this association in blood cancers and solid tumors, he explained.

Cancers known to be linked with infections include liver cancer, which is linked to the hepatitis B and C viruses; cervical cancer, which is closely tied to the human papilloma (HPV) virus; and cancer in the nose and upper throat, which is associated with the Epstein-Barr virus.

A better understanding of the role of bacterial infections in pancreatic cancer may provide new opportunities for early detection and treatment, the paper suggests.

These findings may help pancreatic cancer patients who often want to know, "Why me?" Saif said.

And family members may listen and help out more when patients are asked to change their lifestyle habits, such as not smoking or improving poor dental hygiene. [7 Cancers You Can Ward Off with Exercise]

In addition, these findings "open new doors to research to look into pathways that may develop new therapies to treat this cancer," Saif said.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Article originally on LiveScience.com .

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.