Images: Taxidermy and a Famous Tortoise

Life after death

When Lonesome George died, the last of the full-blooded Pinta Island tortoises of the Galapagos disappeared. But, if a team of taxidermists is successful, his physical presence will live on. About one year after George’s death in June 2012, his frozen remains are in Wildlife Preservations’ New Jersey studio, where work has begun on a mount that will be displayed at the American Museum of Natural History before returning to the Galapagos. In this image, taxidermists measure George.

A Conservation Icon

Lonesome George, shown here days before his death, was estimated to be about 100 years old when he died. A scientist spotted him on La Pinta Island in the Galapagos in 1971, and he was taken to a conservation facility on another island in 1972. He never produced any offspring, but gained international fame as the embodiment of humans’ impact on the natural world.

A Cool Trip

This photo shows Lonesome George’s arrival at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. He was transported from the Galapagos in a thermally insulated box and restabilized after his journey in a walk-in freezer in the museum, said Chris Raxworthy, associate curator of herpetology at the museum.

Unpacking

The conservation and taxidermy team unpacks Lonesome George upon his arrival at the museum. The museum plans to temporarily display the finished taxidermy mount made from his remains this winter, then the mount is expected to go back to the Galapagos.

A History of Exploitation

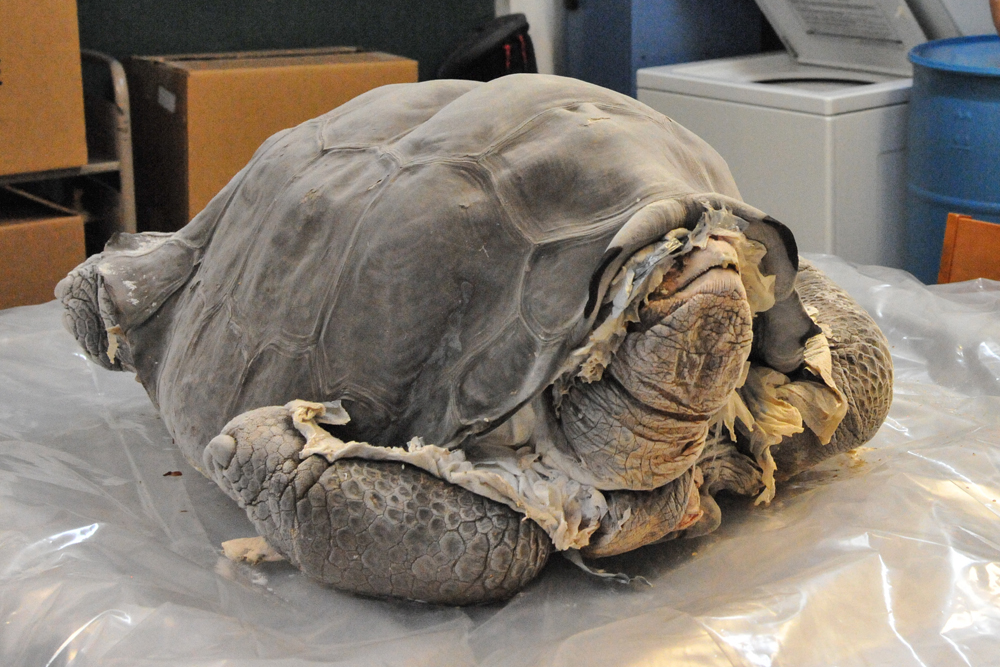

Lonesome George’s frozen remains get a preliminary assessment. Pinta Island tortoises are one among many types of Galapagos giant tortoises. Because these animals can live for long periods without food or water they provided sailors on long voyages with a source of fresh meat. Seafarers’ harvesting, the introduction of foreign species, such as rats, and demand for tortoise oil to light lamps decimated their numbers. Pinta Island tortoises were the fourth to go extinct, according to the Galapagos Conservancy.

A Distinctive Shell

Lonesome George, shown here frozen, had a distinctive saddleback shell, which rose up behind his head allowing him to raise his neck higher than a domed shell would have. Galapagos giant tortoises have both types of shells. The saddle-backed shells evolved on the arid islands so the tortoises could reach further for food, according to the Galapagos Conservancy.

Preparing to Sculpt

Staff of Wildlife Preservations make measurements from Lonesome George. As part of the process, the team of taxidermists led by George Dante, right, must gather as much reference material as possible as they prepare to create the sculpture that will go underneath the tortoise’s tanned skin.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A Tragic Menagerie

George Dante, President of Wildlife Preservations, sprays down Lonesome George. Dante has worked to restore mounts of other extinct species, including the marsupial wolf known as a thylacine, the passenger pigeon and the Carolina parakeet.

Documenting Lonesome George’s Body

As part of the process, the taxidermists create casts of Lonesome George’s head, limbs and tail, as is being done here with one of his feet. These are used as references in the process of sculpting these parts, which must fit under Lonesome George’s skin. When the mount is finished, the tortoise’s shell will contain a support framework made of foam, wood and steel.

Nearly All George, At Least Outside

A cast of Lonesome George’s head for future taxidermy reference. Although his insides are being replaced, every visible part of the finished mount will have come from Lonesome George, except for his eyes. Dante plans to replace these with high quality glass crystal eyes that have been hand painted to match the original coloration.

A Permanent Pose

Multiple casts of Lonesome George’s head. The tortoise’s mount will be arranged in a pose that shows of the long reach of his neck. “When he is actually on display, his head is going to be elevated about 3 feet (0.9 meters) above the ground, probably a lot higher than people imagine (a tortoise) can reach,” Raxworthy told LiveScience.com.