Saber-Toothed Predator Had an 'Embarrassing' Bite

More than 3 million years ago, a strange pouched predator stalked South America with fangs bigger than those of the fearsome saber-toothed cat.

But a new study shows that despite it's imposing dental profile, this ancient carnivore had a bite no stronger than that a house cat — something the researcher called "embarassing." Instead, it packed most of its power in a robust set of arms, strong neck muscles and knack for precision, researchers say.

Named Thylacosmilus atrox ("pouch saber"), the animal was about the size of a jaguar, but "looked and behaved like nothing alive today," paleontologist Stephen Wroe said in a statement. Superficially, Thylacosmilus resembled the saber-toothed cats of the Pleistocene, like the North American icon, Smilodon fatalis. Both have long canines designed to attack large prey, but the animals were separated by at least 125 million years of evolution, researchers say. [Images: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

Thylacosmilus, a marsupial-like carnivore that carried its young in a pouch, went extinct 3.5 million years ago. It had the largest canines of any known saber-toothed beast; its fangs kept growing throughout its lifetime and had roots extending almost into the animal's braincase. The teeth also fit over long sheath-like ridges that extended down from the animal's lower jaw.

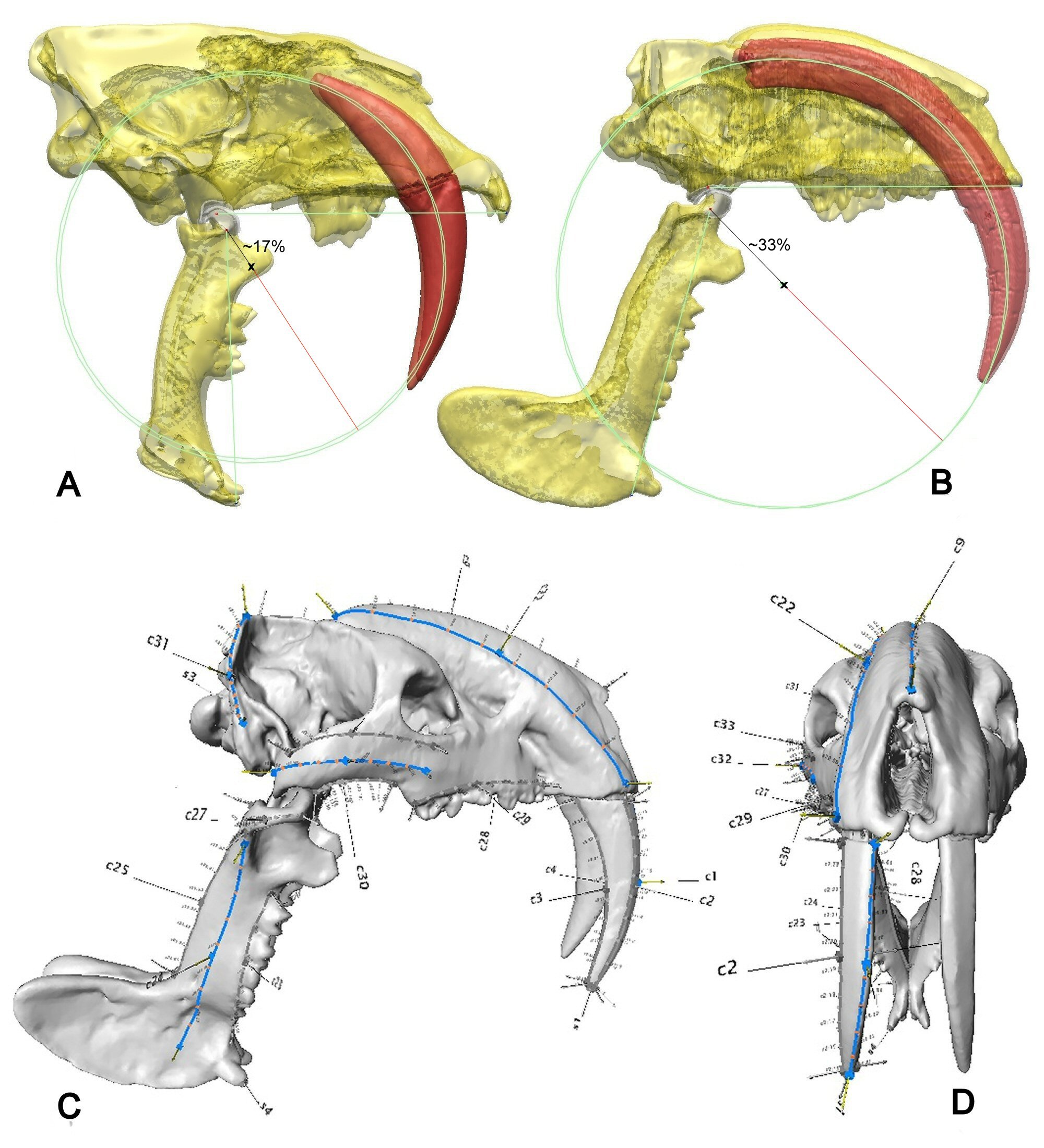

The ancient beasts aren't around today to show off their killing skills, but researchers can reconstruct the force of the predator's bite based on fossilized skulls. Wroe, of the University of New South Wales, and his colleagues made computer models to compare the bite mechanics of Smilodon and Thylacosmilus, as well as a living cat, the leopard.

Previous "crash tests" led by Wroe showed that Smilodon, which vanished only 10,000 years ago, had a rather wimpy bite compared with modern feline predators like the African lion. The new research shows that Thylacosmilus, too, had a weak jaw.

"Frankly, the jaw muscles of Thylacosmilus were embarrassing," Wroe said in a statement. "With its jaws wide open this 80-100 kg [175-220 lbs] 'super-predator' had a bite less powerful than a domestic cat."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To launch an effective attack, Wroe thinks Thylacosmilus must have used "a mix of brute force and delicate precision."

The animal likely used its brawny forearms to clutch and immobilize its prey, Wroe said. The crash tests also showed that Thylacosmilus had stronger neck muscles than Smilodon, which probably helped the pouched predator power its fatal bite. And since its saber-teeth were quite fragile, Thylacosmilus' piercing blow must have been planted carefully, right into the windpipe or major arteries of its prey's neck, Wroe said.

The research was detailed on June 26 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.