14 Adults 'Cured' of HIV: Here's How

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

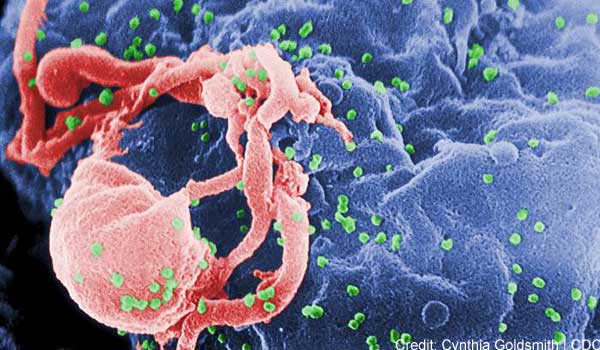

Following the recent news that a U.S. baby has been "cured" of HIV, European researchers now report they have identified 14 adults who appear to have achieved a similar cure.

The 14 adults have been off HIV medication for an average of seven years, and have not experienced a relapse of the disease. Previously, these patients all tested positive for the virus, and took HIV medication for an average of three years before stopping treatment.

These patients still have very low levels of HIV in their bodies that can be detected with sensitive tests, so strictly speaking, they are not completely cured of the disease. But they have achieved what scientists call a "functional cure" — the virus is present at low levels, but does not appear to cause harm. The HIV cure in a U.S. baby, announced earlier this month, was also a functional cure.

In both the adults' and child's cases, researchers suspect early treatment played a role in achieving the functional cure. The 14 adults were treated within 35 days to 10 weeks of infection, which is much sooner than doctors typically give treatment, according to New Scientist. The baby was treated 30 hours after birth.

Early treatment may prevent the virus from finding places to hide in the body that allow the disease to perpetuate, according to the BBC.

However, in most HIV-infected individuals, the disease is not found until much later, [s1] so such early treatment is not possible, the BBC reported. And even people who are diagnosed early may not benefit from early treatment. In the new study, just 5 to 15 percent of HIV patients who received early treatment actually achieved a functional cure.

Still, that's much higher than the percentage of individuals who can naturally control the HIV infection without needing HIV medications. These so-called "elite controllers" are estimated to be less than 1 percent of the population. The 14 adults in the new study were not elite controllers — they didn't have the genetic factors needed to protect them from developing disease.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our results show that early and prolonged [HIV treatment] may allow some individuals with a rather unfavorable [genetic] background to achieve long-term infection control, and may have important implications in the search for a functional HIV cure," the researchers, from the Institute Pasteur in France, write in the March issue of the journal PLOS Pathogens.

Right now, people who take HIV medications (called antiretroviral therapy) are generally recommended to stay on the drugs, even if they have low levels of the virus.

"In my practice … I would start everyone with acute infection on antiretroviral therapy, but in general, I would just continue that therapy and not stop," Dr. Michael Saag, of the University of Alabama Birmingham, told MedPage Today.

In the new study, the patients' antiretroviral therapy was interrupted for a variety of reasons. For example, some decided they no longer wanted to take the drugs, and others took part in a study testing different drug schedules, according to New Scientist.

Pass it on: Some adults who receive early HIV treatment are functionally cured of the disease.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow MyHealthNewsDaily @MyHealth_MHND, Facebook & Google+.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus