Seniors Eye Drugs, Not Lasers, to Improve Eyesight

With the number of seniors receiving treatments for their eyes on the rise, there has been a movement toward using drugs instead of lasers and less invasive surgeries, according to a recent study.

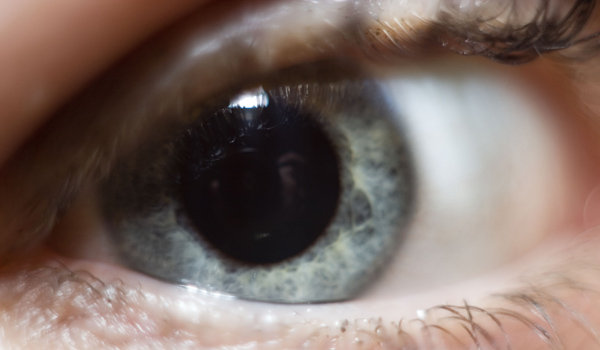

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University used a decade of Medicare records to determine the number of various procedures performed nationwide in the treatment of retinas, the thin, light-sensitive membrane on the inner layer of the eye.

They found new modes of treatment, especially for age-related deterioration of the eye and detachment of the retina from the sclera, the fibrous tissue that forms the outside of the eye , a condition that disrupts vision. Additionally, retina procedures overall were up, rising from 430,000 in 1997 to 1.24 million in 2007, which the authors said could not simply be attributed to increasing numbers of seniors and therefore Medicare enrollees (both 11 percent).

"I think it illustrates how amazingly quickly an effective new therapy can be integrated, even though it involves a new method of administration," said Dr. Pradeep Ramulu of the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins, the lead author on the study.

Overall, the researchers found a move away from lasers and toward injections of medications into the eye for macular degeneration , as well as an increase in minimally invasive surgeries to repair retinas rather than scleral buckling, a procedure in which a band is placed around the eye to hold it against the retina.

"I think the data is very important, reflecting the way Medicare patients have been treated over the last decade, especially with regard to macular degeneration," said Dr. Timothy Olsen, chairman of the Department of Ophthalmology and director of the Emory Eye Center. He characterized the movement as "away from lasers and towards drugs."

But the study researchers cautioned that the trends in eye operations observed in the study only apply to seniors, because "the exclusion of younger patients may miss trends due to trauma, type 1 diabetes, or other common conditions rarely found in those older than 65 years."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The continuing use of some older methods also should not be attributed to a failure to adopt better practices.

"The best practice for any one patient cannot be known," Ramulu said. "However, it would be concerning to see procedures performed when there is longer any good indication for them. We did not see this. In general, we saw the largest numbers for procedures which have a clear role in the treatment of common conditions, which is reassuring."

Olsen said best practices mean that newer doesn't necessarily mean better for all patients. For example, lasers would often be better than drugs for treating macular degeneration due to diabetes.

"That's also reflected in these numbers," he said.

And in another example, Olsen explained that a young patient with a detached retina might need to be treated with both surgery and a buckle on the eye to reattach and hold the retina to the sclera.

"Observing use-patterns adds value, because it demonstrates how disease is treated and can be used to identify possible discrepancies between the best evidence-based treatments for a condition...and current practice patterns," said the Hopkins researchers in their conclusion.

Olsen said the trends the paper showed offer a broad picture of what many in the field have been observing, but said it is likely patient comfort is driving which procedures are used.

He noted, for example, that recurrence of retina detachment was fairly constant between procedures, but "people are more comfortable and their rehabilitation time is quicker" with surgical reattachment instead of scleral buckling.

"You always have to consider the financial drive," said Olsen, saying that the newer procedure may be reimbursed at a higher rate.

But, he added, "I think the minimally invasive nature is really what's driving the field."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus