Great Barrier Reef Samples Frozen for Future Coral Conservation

The Great Barrier Reef, like most other coral reefs around the world's oceans, is under threat from a number of sources, from the steadily acidifying waters of the sea to the impact of commercial fishing. But a new effort to collect samples from the reef has established the first frozen repository of Great Barrier Reef corals that could one day be used to restore coral populations.

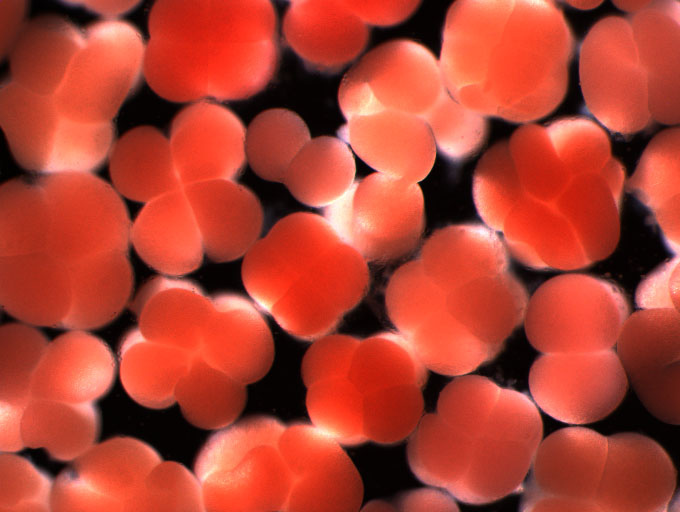

Coral reefs are dynamic ecosystems made up of coral polyps, the hard skeletons they live in, the symbiotic algae that feed them and the myriad fish and other plants and animals that support and are supported by the corals.

Corals are under severe pressure due to pollution from industrial waste, sewage, chemicals, oil spills, fertilizer, runoff and sedimentation from land; climate change; acidification; and destructive fishing practices. Some marine scientists think that coral reefs and the marine creatures that rely on them may die off within the next 50-to-100 years, causing the first global extinction of a worldwide ecosystem since prehistoric times.

Collecting coral

A team of researchers spent two weeks at the end of November collecting sperm and embryonic cells during spawning from two species of coral that live in the Great Barrier Reef, to create a freezer bank of these valuable organisms.

"It turns out we can produce significant numbers of developing larvae using the thawed sperm and that those larvae actually settle," said Mary Hagedorn, a marine biologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute.

Coral settling is the process in which a free-swimming, bowling pin-shaped coral larva metamorphoses into a single polyp baby coral.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is a huge milestone for us because if the larvae couldn't metamorphose and settle, we wouldn’t be able to successfully use the bank for conservation efforts, which is the driving force behind this important research," Hagedorn said.

Hagedorn has already successfully applied this technology to reefs in the Caribbean and Hawaii.

Coral in the bank

The new frozen bank includes samples of two reef-building species of coral, Acropora tenuis and A. millepora, from the Great Barrier Reef, which now reside in long-term storage at the Taronga Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo, Australia. [Images: Expedition to Great Barrier Reef]

Though they remain alive, the banked cells are in a stasis and researchers can thaw the frozen material in one, 50 or, in theory, even 1,000 years from now. The samples, if handled properly, could be placed back into ecosystems to keep the gene pool diverse, which serves to keep populations health and viable.

While scientists have successfully used frozen sperm from coral to fertilize fresh coral eggs, their next focus is on developing techniques to use frozen coral embryonic cells to help restore coral populations. In January, Hagedorn and her collaborators will focus on culturing frozen embryonic cells to see how long they can live.

"Right now there are no tools to help address some of the diseases most devastating to the reef," Hagedorn said. "If we can grow embryonic cells and keep them alive, this technology could be important in battling those coral diseases."