Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Europeans all shared a common ancestor just 1,000 years ago, new genetic research reveals.

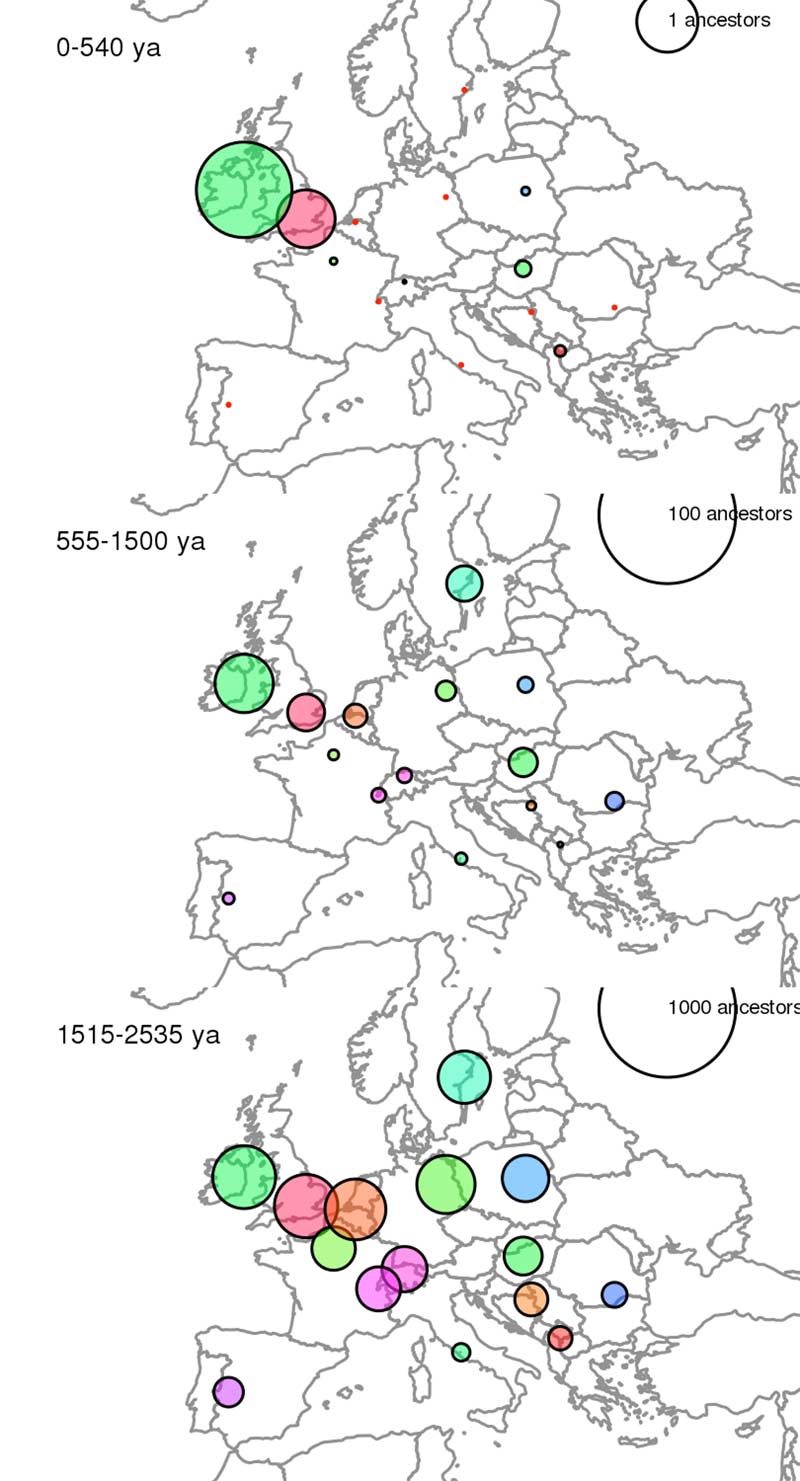

Scientists drew this conclusion, detailed today (May 7) in the journal PLOS Biology, by calculating the length of regions of shared DNA from 2,000 Europeans.

The same technique hasn't been applied to other continents, but people in other parts of the world are just as likely to be closely related, the researchers said.

"In fact, it's likely that everyone in the world is related over just the past few thousand years," said study co-author Graham Coop, a geneticist at the University of California, Davis. [The 10 Things That Make Humans Unique]

All in the family

For more than a decade, researchers calculated theoretically that all people shared common ancestors fairly recently.

To test that theory, Coop and his colleagues analyzed 500,000 spots on the genome of Europeans, from Turkey to the United Kingdom. To untangle European ancestry, they calculated the length of shared segments of DNA, or the molecules that contain the genetic instructions for life. When two people share a longer stretch of identical DNA, they are likely to share a more recent common ancestor, since over time those gene segments evolve and diversify.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers found that all Europeans shared a common ancestor just 1,000 years ago.

There were also some regional surprises.

For instance, Italians are slightly less related to one another than people from other European countries are to one another, perhaps because Italians have had a large, fairly stable population for a few thousand years.

In addition, people from the United Kingdom are more related to people from Ireland than they are to other people from the United Kingdom. That's possibly because many people have migrated from the smaller country of Ireland to the bigger United Kingdom in the past several hundred years, Coop told LiveScience.

The researchers also showed that people in Eastern Europe were slightly more related to each other than were those in Western Europe.

Recent history

That may be he signature of Slavic expansion and migrations, such as those of the Huns and the Goths, about 1,000 years ago, said John Novembre, a population geneticist at the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

The new findings are exciting because they allow researchers to trace much more recent human history.

"In the past human geneticists have been able to focus on the types of population movement that have taken place over tens of thousands of years — like moving out of Africa and into Eurasia," Novembre told LiveScience. "They're starting to see population movements that have taken place in the middle ages."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter @tiaghose. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus