On Hold: Genes That Pause Pregnancy Discovered

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

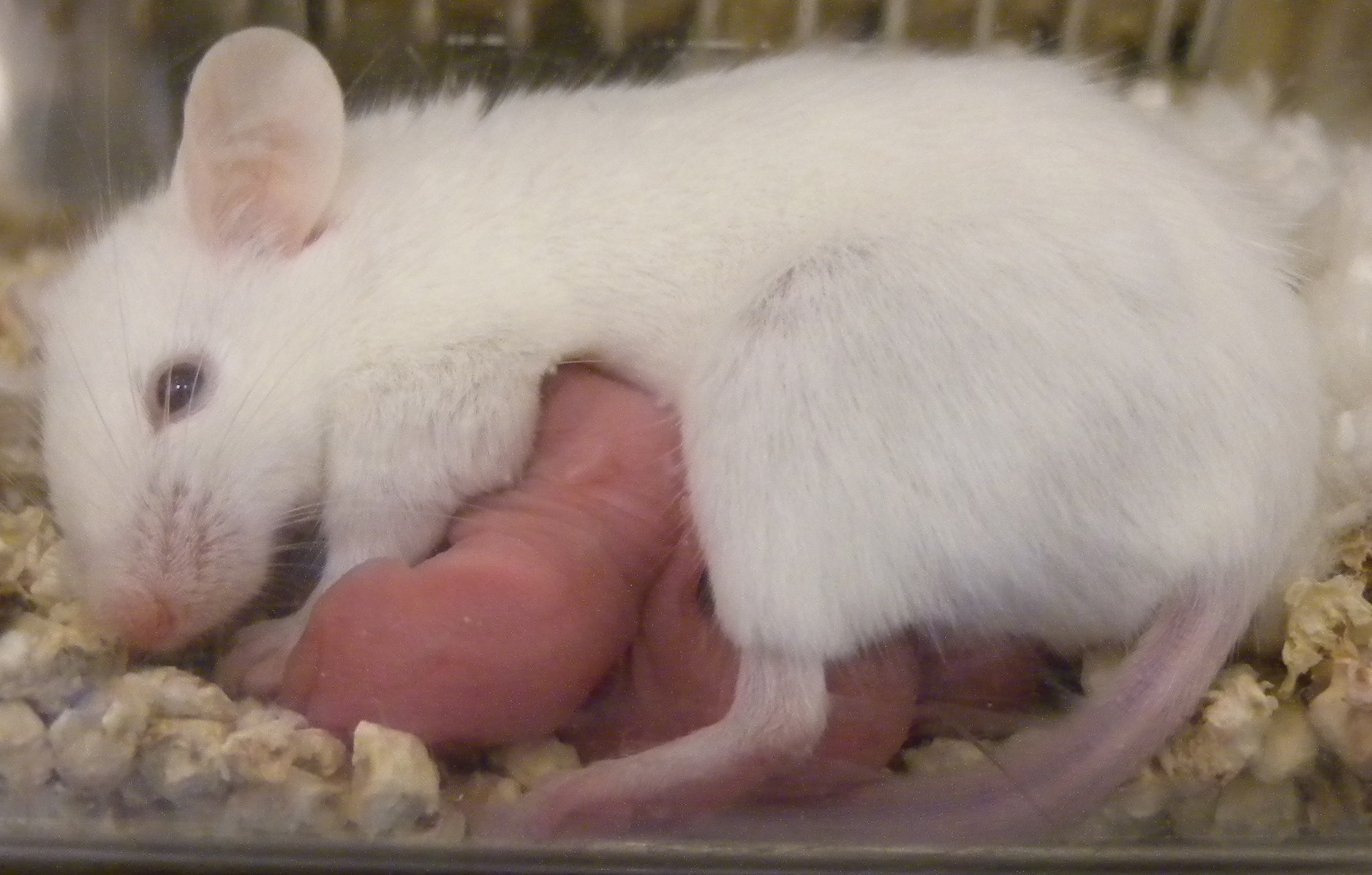

Unlike human women, female mice and some other mammals can delay the onset of their pregnancies, and researchers have now identified the molecular mechanism behind this remarkable ability.

The phenomenon, known as embryonic diapause, is a temporary state of suspended animation that occurs when environmental conditions are not favorable to the survival of the mother and the newborn. A new study, published online today (April 23) in the journal Open Biology, reveals the genes that are responsible for pausing and resuming a pregnancy.

After an egg is fertilized, it forms a cluster of cells known as a blastocyst, which implants in the wall of the mother's uterus. But during diapause, the blastocyst is prevented from implanting and preserved in an inactive state until pregnancy resumes. Yet exactly how this process occurred was a mystery. [Gallery: Evolution's Most Extreme Mammals]

Sudhansu Dey, of Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation, and colleagues were studying the process of embryo implantation in mice when they noticed that a gene called MSX1 was very active just before implantation. They began to suspect that it might play a role in diapause, Dey told LiveScience.

To investigate further, Dey's team used hormones to induce pregnancy delays in mice, mink and Tammar wallabies. During this delayed state, the researchers measured how active the MSX1 gene and other related genes were in generating protein-making instructions. Then, they imaged tissue from the animals to see where the gene was active. Finally, they tested whether these genes were being made into proteins.

They found that the MSX genes were more active when pregnancies were delayed, and found this was true for all three animals. The genes were primarily active in epithelial cells, the type of cells that line body cavities such as the interior of the uterus, results showed. The experiments also confirmed that these genes were indeed making proteins.

Dey said the results are very exciting — they show that MSX genes, which are part of an ancient family of genes, have been preserved over much of evolutionary time, and play an important role in delaying pregnancy under harsh conditions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dey wants to know whether the same genes may enable delayed pregnancies in other animals, such as the polar bear or giant panda.

Ultimately, a deeper understanding of diapause could have implications for humans, Dey said. "If we keep MSX1 maintained at higher levels in human [women], maybe we can extend the receptive phase" for fertilization, he said, though he added that such an extension may be many years away.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus