Breaking the Ice: Earthquakes Trigger Antarctic 'Icequakes'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

SALT LAKE CITY — When the world shakes, so does Antarctica's ice, according to a study presented here April 19 at the Seismological Society of America's annual meeting.

Icequakes are vibrations in glaciers and ice sheets (the massive expanses of glacial ice that cover Antarctica and Greenland). From small creaks and groans to sudden slips equal to a magnitude-7 earthquake, the shaking signals movement in the ice.

Scientists discovered that big earthquakes, including Japan's 2011 Tohoku quake and Chile's 2010 Maule temblor, set off icequakes across Antarctica, just as they triggered earthquakes on land.

"We see pretty clear evidence of triggering [in Antarctica]," said Jake Walter, a geophysicist at Georgia Tech.

The icequakes started after a type of rolling earthquake wave called surface waves (also known as Rayleigh waves) raced through the frozen ice, Walter said. After the two recent major temblors, earthquake monitors picked up a spike in icequakes, which typically hit throughout the day as the ice shifts.

Walter suspects the shaking could shift crevasses or adjust the ice above subglacial rivers, both known icequake triggers.

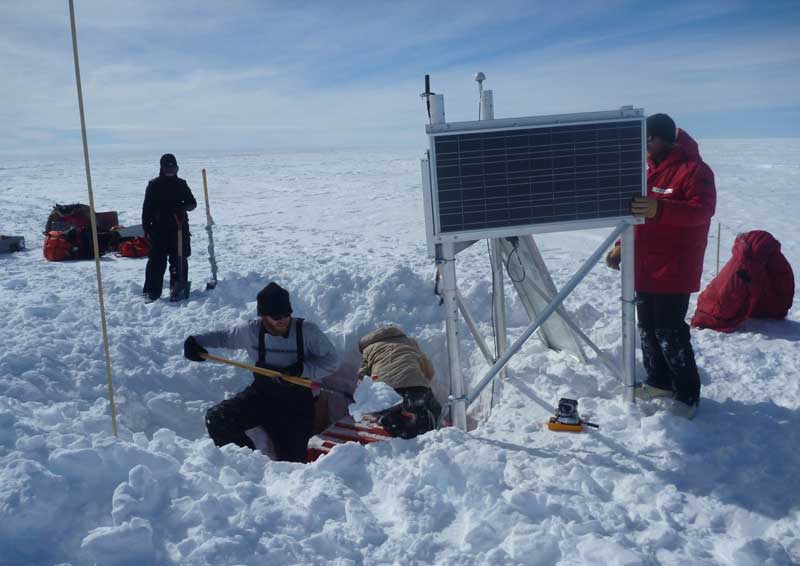

The research team is also taking a closer look at the effects of earthquakes on the Whillans Ice Stream, a fast-moving ice river that flows to the Ross Sea. Whillans — where, this year, researchers recovered the first signs of life from a buried subglacial lake — surges toward the sea two times a day in stick-slip motion, much in the way earthquake faults move. Early results suggest that earthquakes elsewhere on the planet can trigger these sudden slips, Walter said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus