Historic Caribbean Earthquake Was Felt in NYC

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

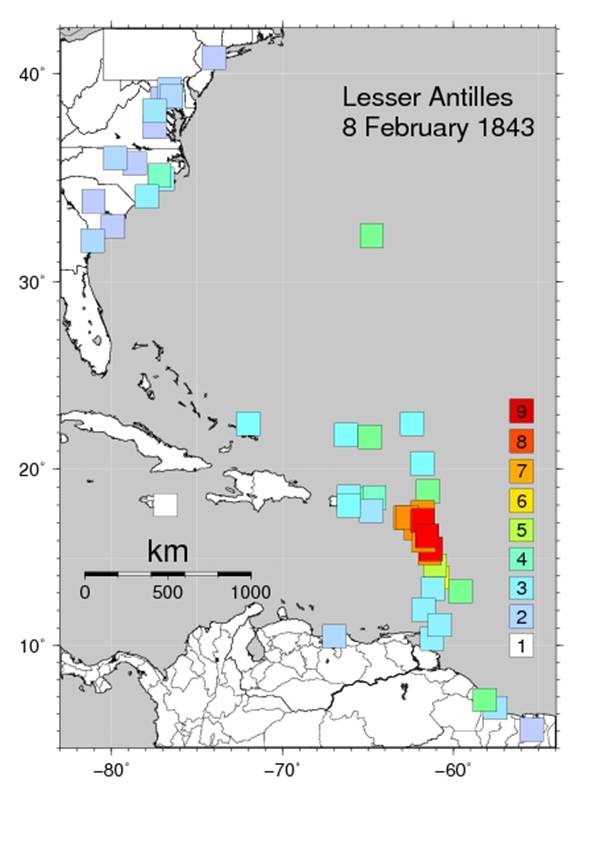

SAN FRANCISCO — More than 150 years ago, a fault ringing the Caribbean shook half the Atlantic, including New York City, with a mega-earthquake. The quake rivaled those that have struck Indonesia in recent years, geologists reported last week at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

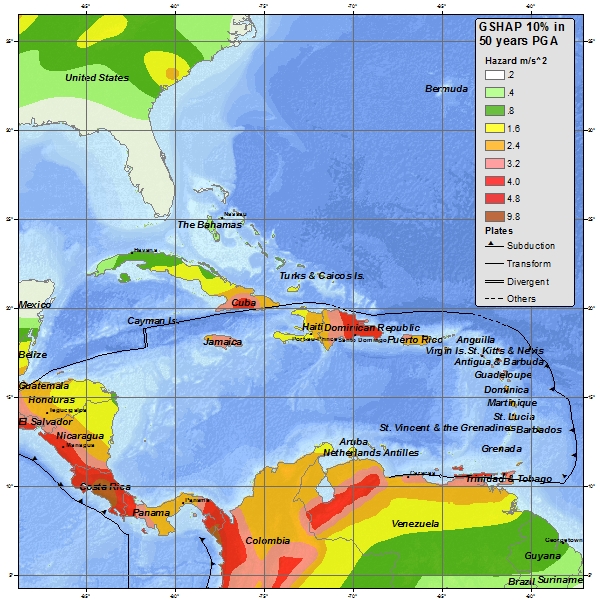

The Caribbean's beautiful tropical islands and coral reefs rise above a complex junction of four major tectonic plates. Many of the islands sit above a subduction zone, where two plates meet and one slides haltingly under the other, down into the Earth's mantle. The Dec. 26, 2004, Sumatra, Indonesia, earthquake, a subduction zone earthquake that generated deadly tsunamis, has galvanized scientific interest in potential quake hazards from the Caribbean's similar earthquake-producing faults.

The Feb. 8, 1843, Lesser Antilles earthquake was in many ways remarkably similar to the magnitude-8.7 earthquake that struck Sumatra just one year later, in 2005, researchers reported at the meeting. [The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

Historical sleuthing by Francois Beauducel and Nathalie Feuillet of the Paris Institute of Earth Physics upwardly revised the temblor's estimate of magnitude to 8.5 (from a previous estimate of 7.8).

Maps from the French national marine service revealed that many palm-covered islets in the bay at Pointe-à-Pitre, the biggest city on the island of Guadeloupe, disappeared between 1820 and 1869, Feuillet told OurAmazingPlanet. The islets likely subsided, or dropped below sea level. The stress of the two plates stuck together makes the earth's crust flex and warp. After the earthquake, the deformed crust rebounds in some areas and drops down in others.

Portions of Antigua subsided up to 10 feet (3 meters), Feuillet said. Wharfs at the shore of Pointe-à-Pitre sunk one foot (33 centimeters), she found. Cliffs along the island collapsed, and historic accounts describe 5-foot-high (1.5 m) mud fountains.

Combining the 19th-century records of such effects with modern earthquake models helped Beauducel and Feuillet pin down both the quake's magnitude and the location of the fault rupture, the spot where the subduction zone tore apart.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The only way to explain the subsidence of the islands is to have a rupture … in the very deep part of the subduction zone, between 40 and 60 km (25 to 40 miles) depth," Feuillet said. Such as depth is comparable to that of the 2005 Sumatra quake, the researchers said.

The quake was felt up and down the East Coast, including in New York City, Washington, D.C., Raleigh, N.C., and Charleston, S.C., said Susan Hough of the U.S. Geological Survey. Hough also unearthed reports of shaking at three locations in South America, she said.

But, just as with the 2005 Sumatra quake, there was no giant wave on Feb. 8, 1843. Reports describe a 4-foot (1.2 m) wave in Antigua, but no significant tsunami arose, Feuillet said. Even so, several thousand people died in Pointe-à-Pitre from fires and damage caused by the severe shaking.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus