New Theory on Formation of Solar System's First Stuff

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

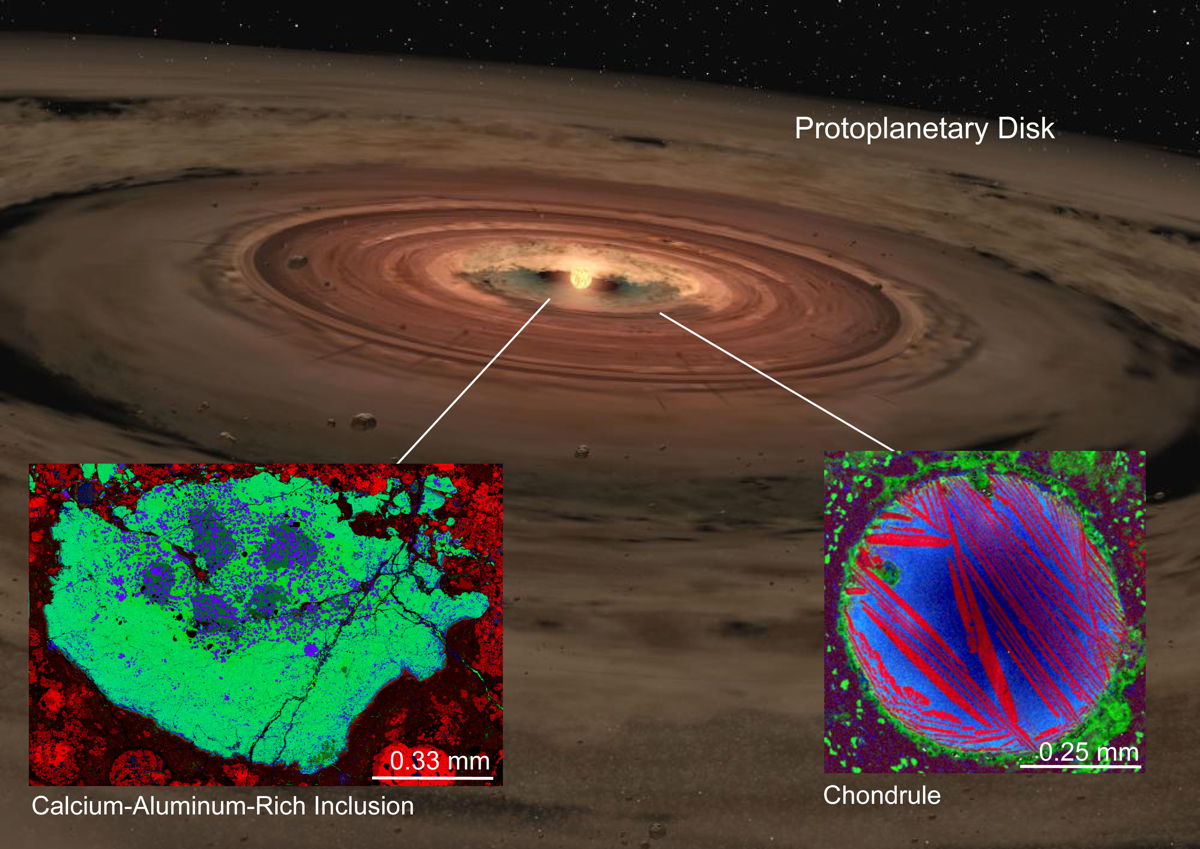

A new view of the solar system's early days proposes that the first two kinds of solid materials — the precursors of space rocks and ultimately planets — both formed at the same time.

When the sun was born about 4.6 billion years ago, it was surrounded by a cloud of gas and dust that eventually became the asteroids, comets and planets. An initial step in that process had to be the generation of clumps of solid material.

Previously, researchers believed the two known types of early solids formed several million years apart from each other. But a new dating technique from the University of Copenhagen's James Connelly and fellow researchers shows different results.

This means the early days of the solar system look different than previously thought. Connelly and his teammates propose their new model in a paper published in the Nov. 2 issue of the journal Science.

Gas and dust compression

Connelly's team focused on two types of solids: calcium-aluminum–rich inclusions (CAIs) and chondrules. Both of these solids are found in meteorites, which are pieces of space rocks typically billions of years old that find their way to Earth and are often discovered by scientists and amateurs.

These materials "have records in them of events and processes in the early part of the solar system," Connelly said, particularly of the time that the sun and planets were forming from a spinning disk more than 4.5 billion years ago. [Planetfall: Wonders of the Solar System (Photos)]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

CAIs form from molten gas droplets under temperatures higher than 1,880 degrees Fahrenheit (1,030 degrees Celsius, or 1,300 degrees Kelvin), while chondrules are dust collections that rapidly melt and cool in a lower temperature region of less than 1,340 degrees Fahrenheit (727 degrees Celsius, or 1,000 degrees Kelvin).

Under the new model of the solar system's formation, the spinning disk that eventually formed the sun and the planets had a large amount of energy within it. Particles were flattening into planes along the disk. In the center, the sun formed as material lost momentum and began condensing.

As the material collapsed on to the protoplanetary disk, huge shockwaves formed that produced "flash" heating, or warmth that began and then dissipated within a matter of hours. These surges of energy affected the CAIs and the chondrules, Connelly said.

The finding could be important, because it illustrates a generic way that all protoplanetary disks in the known universe may have formed solids.

Other dating methods said that the energy from our solar system's protoplanets, as they whizzed around in their orbits, predicted the chondrules formed some 2 million years after CAIs did. However, this timing didn't jive with astronomical observations of other planetary systems, which predicted a shorter formation period.

The other model, Connelly said, implied "there is something unique about our solar system that allows these inclusions to be formed. It looked as if these things were lasting a bit too long."

A new method of dating

The old dating method relies on measuring the amount of aluminum 26, which is a radioactive form, or isotope, of aluminum, present in meteorites to date the solar system. But there is one weakness with this technique, Connelly said: Using this form of aluminum assumes it was distributed evenly throughout the solar system.

If two objects formed at the same time in different locations of the disk, they may not necessarily have the same amount of this aluminum isotope inside of them because there may be different proportions of aluminum in different locations. The old assumption was that if the aluminum proportions were different, they formed at different times.

To come up with the new solid history, Connelly and his team adapted techniques he learned at the Royal Ontario Museum years ago while dating zircon minerals.

The researchers broke apart meteorite samples, washing and gradually dissolving them to partition lead from the rest of the sample, removing contaminants that can affect the dating process.

Connelly's team used mass spectrometers to measure the isotopic composition of lead and uranium, and used the known rate of the decay of uranium to determine absolute ages of CAIs and chondrules in the meteorites.

Uranium and lead are commonly used to date geologic events on Earth because isotopes of uranium have suitable half-lives (meaning, the time in which half the particles decay to lead) for this work.

In meteorites, using the same process is more challenging because the uranium and lead are in small quantities. However, uranium-lead dating is the best method to learn about the early solar system because dating with it is so precise, Connelly said. It can differentiate events that are less than a million years apart.

The team's new "preferred estimate" for the age of CAIs is 4.56730 billion years, plus or minus 160,000 years.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus