'Noseless Lemur' Fossil Actually a Fish

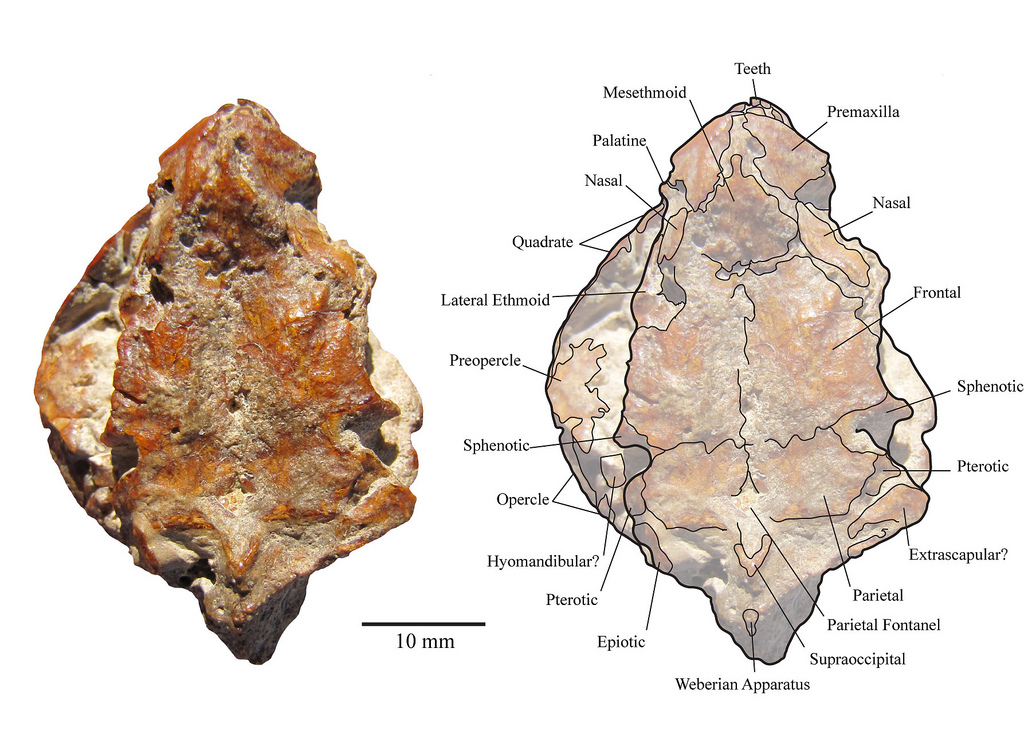

A one-of-a-kind fossil thought for more than 100 years to be a lemur without a nose is not a primate at all, scientists have found. It's a fish.

Oops.

A new analysis of the 2-inch (5-centimeter)-long fossil corrects an error first made in 1898, when a fossil collector named Pedro Scalabrini sent the specimen to Argentine naturalist Florentino Ameghino. Apparently having an "off" day, Ameghino gave the fossil a quick look and classified it as Lemuridae, or part of the lemur family. He named it Arrhinolemur scalabrinii, which translates to "Scalabrini's lemur without a nose."

Ameghino noted that the supposed lemur fossil was odd, and suggested it be assigned to a new order of bizarre mammals, which he suggested naming Arrhinolemuroidea.

Ameghino was a controversial figure in paleontology, said study researcher Brian Sidlauskas, an assistant professor of fisheries at Oregon State University. Ameghino wanted to prove that mammals originated in South America (they didn't), so "he really wanted things to be mammals," Sidlauskas told LiveScience.

Ameghino was also making his identification based on only bits of the fossil, which was still mostly encased in rock when he saw it, Sidlauskas said. [Image Gallery: Freaky Fish]

Over time, the single fossil, which dates back to between 6 million and 9 million years ago, remained the only example of A. scalabrinii ever found. About 50 years after Ameghino's mistake, American paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson suggested the fossil might not be a mammal, but a fish. The wheels of science continued their slow grind in 1986, when another scientists named Alvaro Mones suggested the possible fish family might be Characidae, a group that includes popular aquarium fish such as tetras.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But no one had ever done a full taxonomic work-up on the fossil. Two years ago, Argentine scientists Sergio Bogan and Federico Agnolin decided to change that. They contacted Sidlauskas, who had researched South American fishes during his doctoral work, along with Smithsonian ichthyologist Richard Vari. This dream team of fish experts did a complete examination of photos of the fossil.

They concluded that no one had ever got this "noseless lemur" quite right. In fact, Sidlauskas said, the fossil is a fish from the Anostomidae family, a group of South American freshwater fish.

The fish is of the genus Leporinus, another clue to the misidentification, Sidlauskas said: Fish of this sort have somewhat mammal-like teeth, of the kind that might be found on a rabbit.

Today, between 90 and 100 species of Leporinus swim in South American lakes and rivers, Sidlauskas said. The fossil appears to be of an extinct variety

Understanding how the fish fossil fits into history helps researchers date the biodiversity of South American fish, one of the richest groups of fish fauna on the planet, Sidlauskas said.

"It tells us something about biodiversity in the past, so now we know that 6 to 9 million years ago, a fish very much like the ones we have today was in that place and time," he said.

Sidlauskas and his colleages reported their findings in the journal Neotropical Ichthyology.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus