Life on Mars Time: Scientists Adapt to Curiosity Rover's Red Planet Trek

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

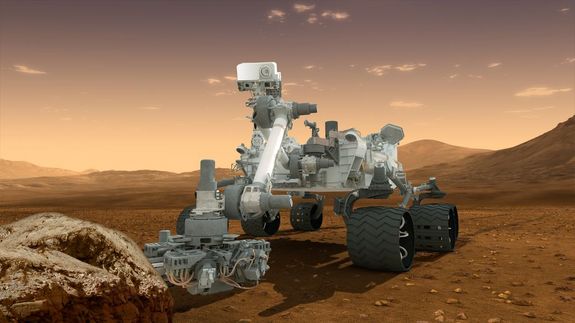

Now that NASA's new Mars rover Curiosity is on the ground, the work begins — not just for the robot, but for many humans back on Earth.

It will take teams of dozens of scientists working around the clock to monitor and guide Curiosity as it explores its new home, Mars' Gale Crater.

"There are a lot of long hours, but the adrenaline will last for a while," Curiosity mission systems manager Michael Watkins said during a news briefing today (Aug. 7) at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif. "These are the days that people worked five and 10 years for, going on right now."

Curiosity, the centerpiece of the $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory mission, landed on Mars Aug. 5 after launching last fall. The car-size rover is slated to last at least two years on Mars studying whether the Red Planet ever had the water and other conditions thought necessary to host life. [Gallery: Curiosity's Landing Day at JPL]

Living on Mars time

While Curiosity is fairly autonomous, equipped with cameras at front and back to detect obstacles such as boulders in its path and avoid them, the rover will also receive intensive instructions from people back on Earth.

For the first 90 Mars days, or Sols, the teams in charge of each of Curiosity's 10 science instruments will put the rover through its paces to check them out. These teams will live vicariously through Curiosity, seeing what it sees on large television screens and even operating on Mars time, where the day lasts 24 hours and 39 minutes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The shifts are based on Mars time," said Chuck Baker, mission planner for the cruise portion of Curiosity's trip from Earth to Mars. "You see a lot of people who wind up working weird hours. A lot of people have cots in their offices because getting sleep can get a little hairy."

Baker estimated that around 20 to 50 people will be working on console at any given time in Mission Control, which is based at JPL.

Hello Mars, are you there?

And because of the distance between Earth and Mars, radio signals sent from Mission Control take time to reach the Red Planet. For now, messages to Curiosity are relayed via NASA's two orbiters circling the Red Planet: Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, but direct Earth-to-rover communications are due to be established soon.

"We can't control it in real time because of the gulf of distance between Earth and Mars," Baker told SPACE.com. The lag can be as much as 20 minutes one way, and as little as 10 minutes one way; it just depends on where Mars is. That's pretty important when you send commands; that needs to be taken into account."

Some team members will monitor the rover's navigation software, while others will make sure its telecommunications systems are functioning. Additional teams will be devoted to each of its science instruments, such as its Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD), which will measure the ambient radiation on Mars, its Mast Camera (Mastcam), a camera mounted on its tall mast to take panoramic photos of the scene, and its ChemCam, which will zap rocks with a laser to analyze their chemical makeup. Furthermore, some mission managers must plan ahead and instruct Curiosity on where to explore next.

"There's a group of people that actually plan with an animation with real imagery and determine where it is we're going to go," Baker said. "That gets turned into sequences and then gets sent up to the spacecraft."

Still other teams will analyze the science data as it comes down, spending months and years studying the wealth of information Curiosity will reveal.

Overall, hundreds of people will contribute to the mission of this one robotic explorer.

"This is the closest you can get to being a Martian astronaut," Baker said. "We call ourselves Martians because of that very fact. You feel as though you're literally part of what's going on. The mission becomes a part of you, it truly does."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus