Drug-Resistant Germs Infiltrate Pristine Arctic

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

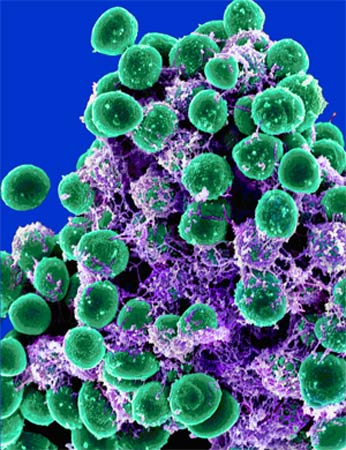

There may be no place on the surface of Earth where germs dangerously resistant to antibiotics have not spread. Swedish researchers now find drug-resistant bacteria have infiltrated one of the last outposts of wilderness, the Arctic, hitching a ride way up north on birds. The fact that these microbes have now reached one of the most remote places on Earth sheds light on how rampant such germs have become closer to home, researchers said. The use and misuse of antibiotics over the past few decades have led to the evolution of micobes resistant to many of the most common drugs against them, rendering more and more bacterial infections difficult or impossible to treat. "Escalating resistance to antibiotics over the last few years has crystallized into one of the greatest threats to well-functioning health care in the future," said researcher Jonas Bonnedahl, an infectious disease physician at Kalmar University in Sweden. Extremely surprised The scientists investigated bacteria from the Arctic with the assumption that germs in such distant climes would be far beyond the reach of human influence. "We were extremely surprised" to find otherwise, said researcher Björn Olsen, an ornithologist and infectious disease physician at Uppsala University in Sweden. Olsen, Bonnedahl and colleagues ventured out into the Arctic aboard the icebreaker Oden. They made their way onto the shores of northeastern Siberia, northern Alaska and northern Greenland via inflatable boats and took fecal specimens or rump swabs from 97 birds. Bacteria from these samples were cultivated directly in special laboratories onboard the icebreaker and further tested against 17 different drugs at a microbiological laboratory in Sweden. The scientists found eight of the samples displayed antibiotic resistance. Four of the samples proved resistant to four to eight of the 17 drugs tested. "We took samples from birds living far out on the tundra and had no contact with people," Olsen said. The fact that these samples possessed drug-resistant bacteria "further confirms that resistance to antibiotics has become a global phenomenon and that virtually no region of the Earth, with the possible exception of the Antarctic, is unaffected." Other pole, too? Even the Antarctic might one day get invaded by these bacteria "via human activities such as research bases," Olsen added. Scientists had known birds could host drug-resistant germs — migratory Canadian geese tested near the eastern shore of Maryland, for instance, or black-headed gulls in the Czech Republic. But "it's alarming to find that these bacteria out on the tundra," Olsen told LiveScience. "They're leaking out to all over. It's just a sign of how bad the situation with antibiotic-resistant bacteria is." The researchers note a number of bird species they studied spent the winter at warmer latitudes in up to six different continents, which is where they may have acquired the drug-resistant bacteria. The scientists detailed their findings in the January issue of the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

- Video: Making Killer Flu

- What Do Antibiotics Do?

- Top 10 Mysterious Diseases

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus