Soft Robots Make World Safer for Humans

Today's rigid robots don't leave much room for error when trying to precisely pick up a homemade bomb on the battlefield or swiveling around at fast speeds inside a car factory. A new generation of softer robots could not only do the same jobs with less complex "brains" built into their software programs, but also operate more safely around squishy humans nearby.

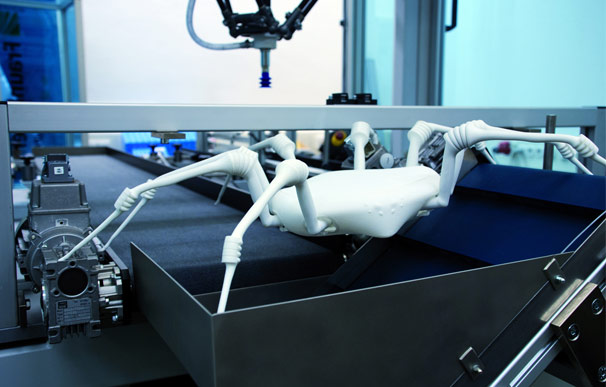

That vision has driven both U.S. military and civilian programs to create flexible, air-filled robot bodies and arms capable of working well in almost any situation — regardless of mistakes made by humans or machines. The inflatable robots can "tune" themselves to different scenarios where they might need to let out air to soften or pump up the pressure to become rigid.

"They are much safer around humans and much more forgiving in terms of interaction," said Chris Jones, director for research advancement at iRobot. "You can contrast a compliant (flexible) robot with a heavy, highly accurate, expensive industrial robot arm that is moving around very fast and very precisely."

The iRobot company already supplies rigid robots for helping the U.S. military dismantle improvised explosive devices and its popular Roomba vacuums for use in homes. But it has spent the past several years exploring new robot possibilities in its Advanced Inflatable Robots program, and has also drawn funding from the U.S. military.

One Army notice dated April 17 detailed plans for working with iRobot to develop an inflatable robot arm. A soft robot arm could fold its "hand" gently around a doorknob before inflating to a hard, stiff grip — an action that requires much less complicated orders compared to positioning a rigid robot's hard claw or hand.

"If you want to grab a door knob and you're using a more traditional robot with rigid hands or grippers, you have to be very precise about how you move that arm and hand," Jones told InnovationNewsDaily. "That puts a lot of complexity in the mechanism itself — complexity adds to costs in the motors and sensors — or places a lot of complexity on the human operator if this is a teleoperated system."

The safety factor for humans is also important as more robots enter factories and homes. Robots have only accidentally killed a handful of people so far, but their growing numbers could potentially lead to more tragic incidents without precautions. [Running with Chainsaws: A History of Robot Violence]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But inflatable robots present their own challenges. Moving or bending an inflated arm has required cables connected to motors or pneumatic bellows that act like accordions. Similarly, researchers have also begun considering inflatable materials that can withstand wear and tear as well as rigid robots — or perhaps act like self-healing bladders if punctured.

"They have a lot of compelling potential advantages," Jones said. "The question remains — can those advantages be truly realized?"

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.