Jewel-like Nanowires Pretty As Well As Efficient

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

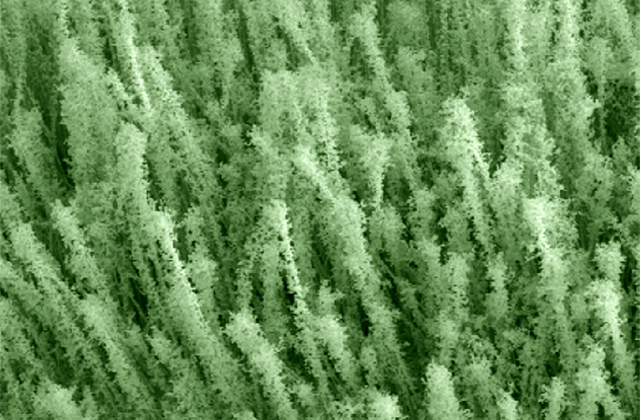

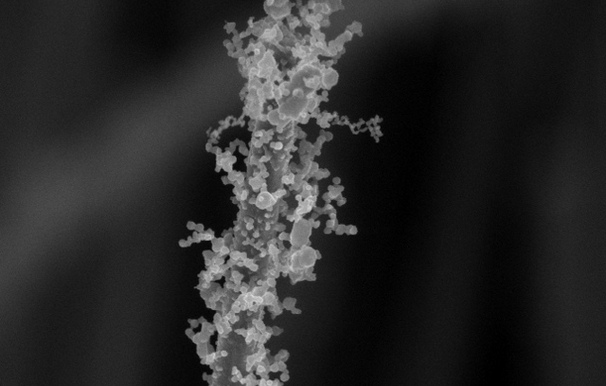

Engineers at Stanford University have found a way to add these delicate, bulbous decorations to nanowires that are about 1/1000th the width of a human hair. The decorations are could be important to creating more efficient batteries, solar cells and other nanotechnology-enabled inventions in the future. Several research groups have come up with different ways to add tiny hairs, branches, bumps and folds to nanowires. But the new Stanford method is simple, works for wires made of many different materials and loads up the wires with an extra dose of decorations, according to a paper the researchers published April 11 in the journal Nano Letters.

Many research groups are studying nano-size wires and tubes to go in microchips, water filters, batteries and more. One major goal for nanowire researchers is finding easy ways to stably stick nano-size particles on the wires. The particles increase the surface area over which a chemical reaction can happen, making the wires more efficient. In one lithium-ion battery study, for example, decorated nanowires created six times more energy than undecorated wires. In another study of solar power tech, decorated nano-size rods absorbed more visible light and created 29 times more current than undecorated rods.

To make their decorated wires, the Stanford researchers dipped plain, undecorated nanowires in a solution of metal salts. After the wires dried, either in air or in nitrogen gas, the researchers gave them the crème brulée treatment by blasting them with a flame for up to a minute. The flame, which must be at least 600 degrees Celsius (1,112 degrees Fahrenheit), quickly evaporates and burns any liquid left in the metal-salt coating. As the coating burns, it creates gases that flow outward from the nanowire, depositing tiny nanoparticles in chains that radiate from the wire like branches. "It created these intricate, hair-like tendrils filled with lots of nooks and crannies," Xiaoli Zheng, who led the study, said in a statement.

The researchers tried the method with several combinations of nanowires and dip solution, showing the new technique works with wires and dip made of different materials. By changing the proportions of ingredients in the dip solution and the number of dips the wires undergo, the researchers found they could control how dense the decorations are. That level of control is helpful to researchers and may make the technique popular, Zheng said.

Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus