Strange Organism Has Unique Roots in the Tree of Life

Talk about extended family: A single-celled organism in Norway has been called "mankind's furthest relative." It is so far removed from the organisms we know that researchers claim it belongs to a new base group, called a kingdom, on the tree of life.

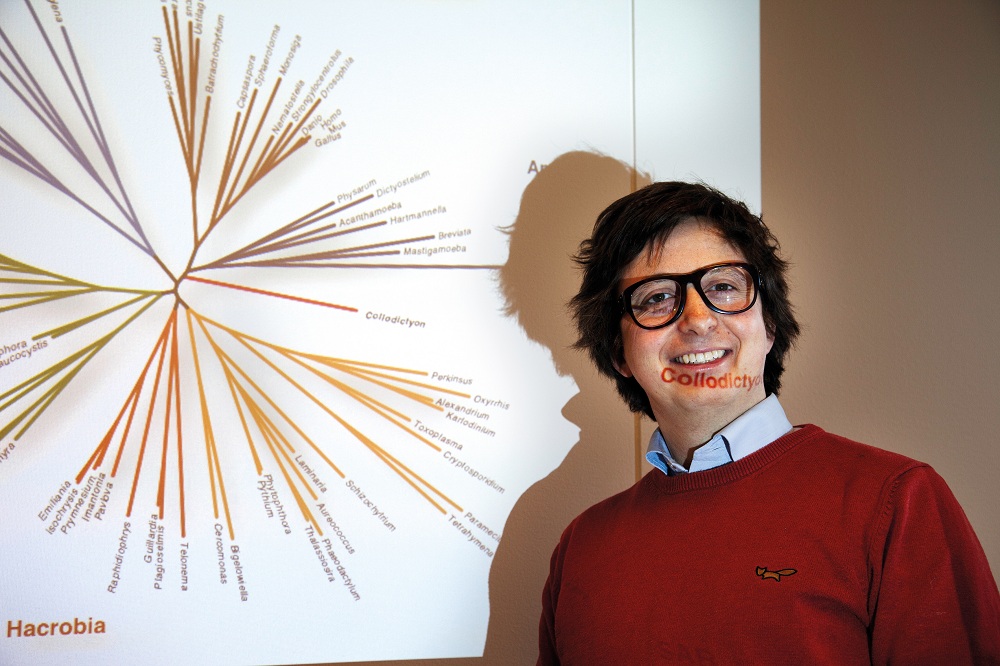

"We have found an unknown branch of the tree of life that lives in this lake. It is unique! So far we know of no other group of organisms that descend from closer to the roots of the tree of life than this species," study researcher Kamran Shalchian-Tabrizi, of the University of Oslo, in Norway, said in a statement.

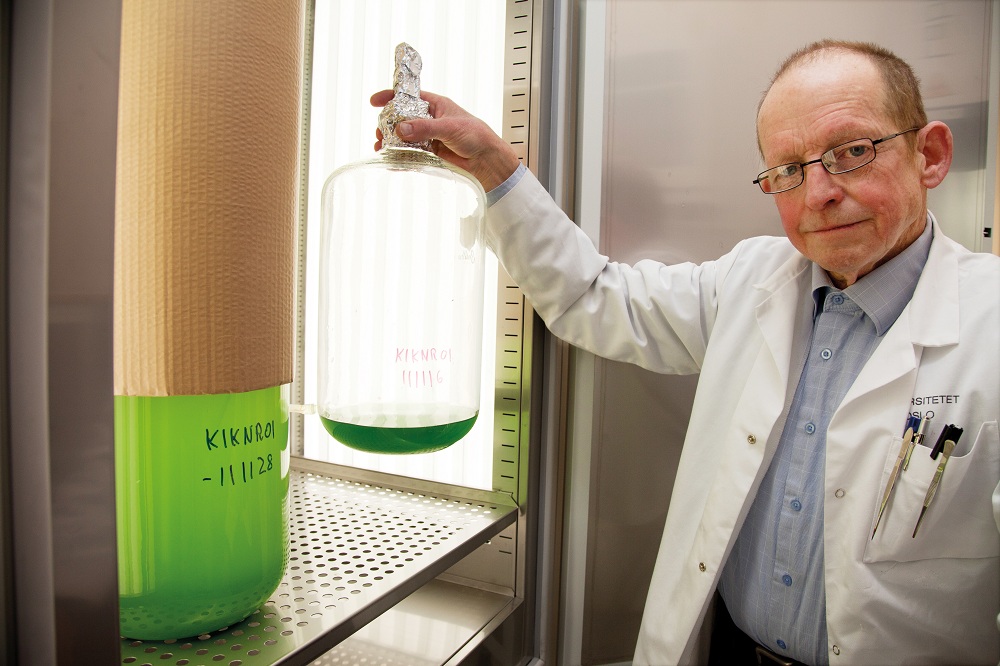

The organism, a type of protozoan, was found by researchers in a lake near Oslo. Protozoans have been known to science since 1865, but because they are difficult to culture in the lab, researchers haven't been able to get a grip on their genetic makeup. They were placed in the protist kingdom on the tree of life mostly based on observations of their size and shape.

In this study, published March 21 in the journal Molecular Biology Evolution, the researchers were able to grow enough of the protozoans, called Collodictyon, in the lab to analyze its genome. They found it doesn't genetically fit into any of the previously discovered kingdoms of life. It's an organism with membrane-bound internal structures, called a eukaryote, but genetically it isn't an animal, plant, fungi, algae or protist (the five main groups of eukayotes). [Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

"The microorganism is among the oldest currently living eukaryote organism we know of. It evolved around one billion years ago, plus or minus a few hundred million years. It gives us a better understanding of what early life on Earth looked like," Shalchian-Tabrizi said.

Mix of features

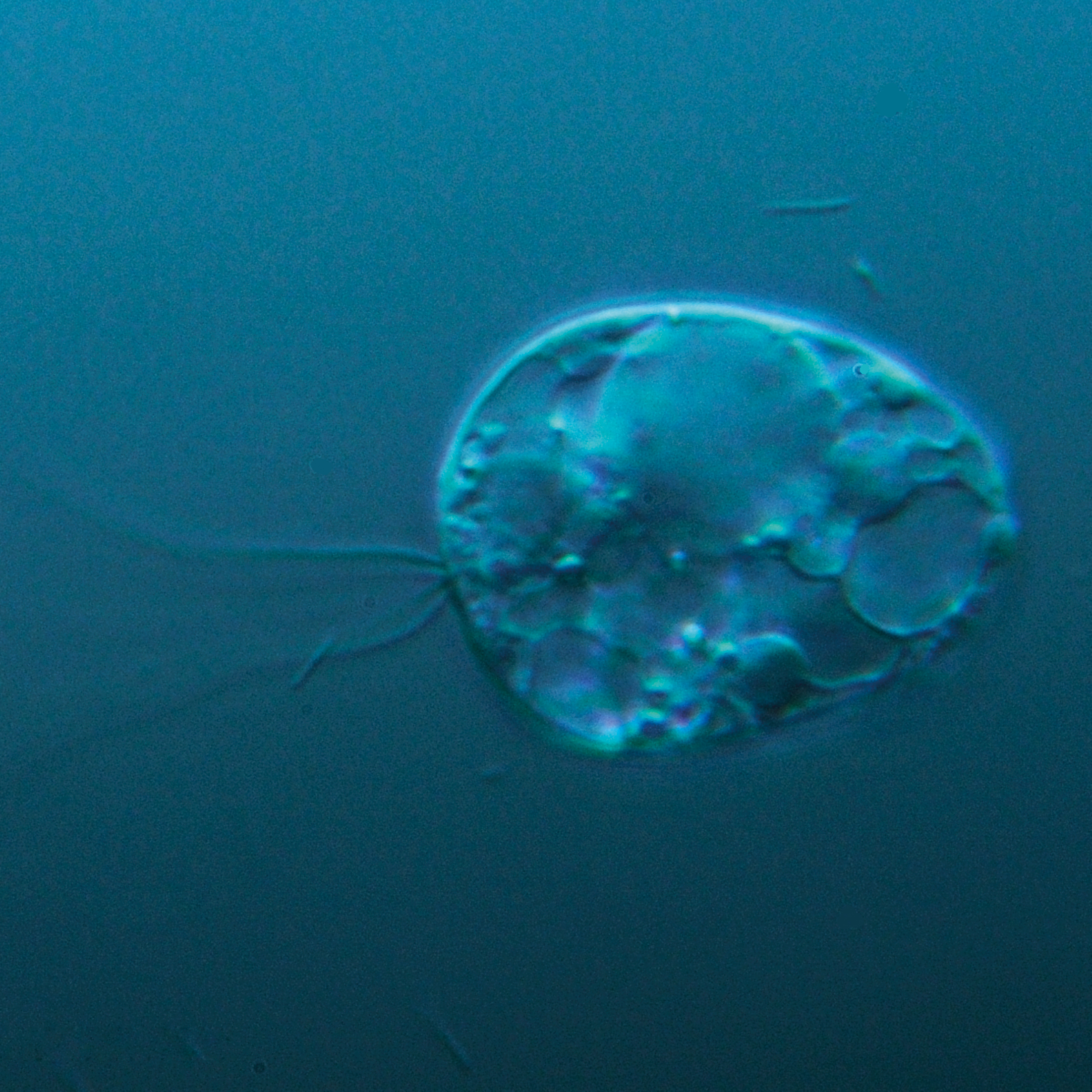

What it looked like was small. The organism the researchers found is about 30 to 50 micrometers (about the width of a human hair) long. It eats algae and doesn't like to live in groups. It is also unique because instead of one or two flagella (cellular tails that help organisms move) it has four.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The organism also has unique characteristics usually associated with protists and amoebas, two different branches. This left researchers wondering where the microorganism fits into the tree of life. They analyzed its genetic code to see how similar it is to organisms that have already been genetically catalogued.

"We are surprised," said study researcher Dag Klaveness, also of the University of Oslo, because the species is unique. They compared its genome with those in hundreds of databases around the world, with little luck. In all that looking they "have only found a partial match with a gene sequence in Tibet."

New life

The researchers think this organism belongs in a new group on the tree of life. Researchers can't say for certain if other organisms previously classified as protozoans are in this same branch without their genetic information. Its closest known genetic relative is the protist Diphylleia, though other organisms that haven't been analyzed genetically may be closer relatives.

"It is conceivable that only a few other species exist in this family branch of the tree of life, which has survived all the many hundreds of millions of years since the eukaryote species appeared on Earth for the first time," Klaveness said.

Because it has features of two separate kingdoms of life, the researchers think that the ancestors of this group might be the organisms that gave rise to these other kingdoms, the amoeba and the protist, as well. If that's true, they would be some of the oldest eukaryotes, giving rise to all other eukaryotes, including humans.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter, on Google+ or on Facebook. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on Facebook.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to correct the fact that it stated amoebas and protists were two kingdoms when in fact they are just two different branches within eukaryotes.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.