Lumbering Sea Cows Were Once Plentiful and Diverse

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

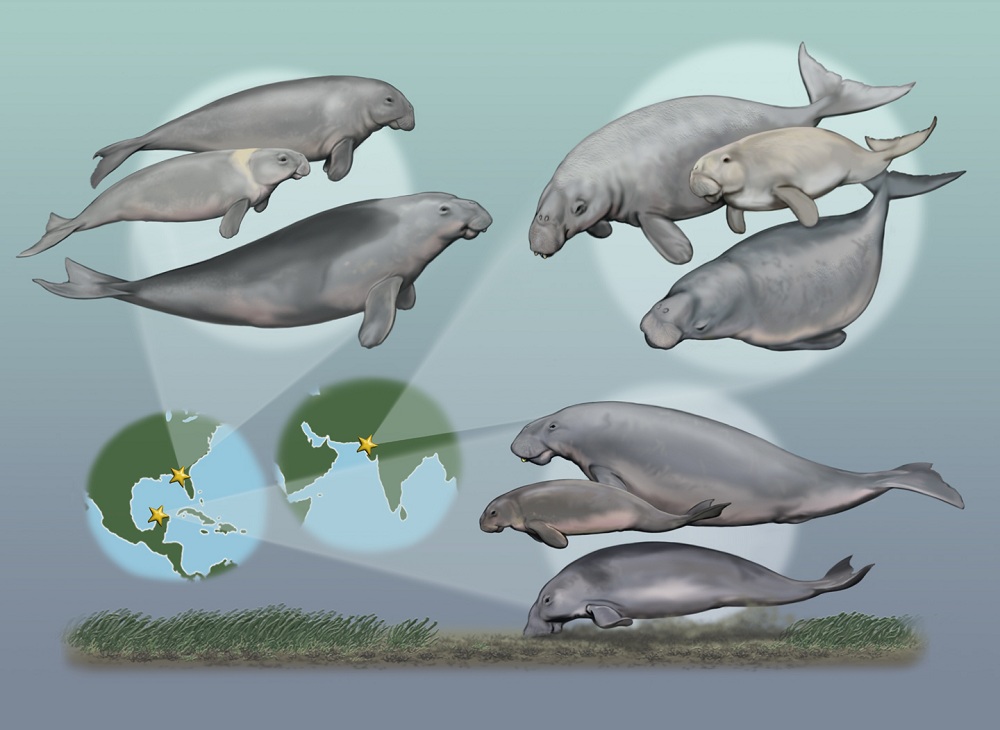

Today's sea cows are lonely: They share their habitat only with others of their species. This wasn't always the case, new research suggests. In the past multiple species of sea cow lived together in harmony.

Sea cows, also known as Sirenians, are defined by four species, the best known in the United States being our Florida resident, the manatee. There are two other species of manatee in the Atlantic Ocean, as well as the dugong, from the Indo-Pacific.

Searching for sea cows

The researchers found multiple examples of Sirenians in the same fossil bed at the same depth — evidence the two species would have lived in the same area at the same time.

"We were culling through the fossil record of sea cows and finding those few cases we could be certain that these things lived together," study researcher Nicholas Pyenson, a curator of fossil marine mammals at the Smithsonian Institution, told LiveScience. "In some cases we found the fossils literally on top of each other."

Before modern times, up to three species of these big herbivores (they eat mainly sea grasses) could be found together in the same area. This suggests that the environment and food sources for ancient sea cows were different in the past, but researchers weren't sure how.

They analyzed the fossils of species seen living together in the past during three different time periods and locations: the late Oligocene (23 million to 28 million years ago) in Florida, the early Miocene (16 million to 23 million years ago) in India and the early Pliocene (3 million to 5 million years ago) in Mexico.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Different diets

Whether one or more species can survive in the same habitats isn't about aggression against each other, but the two species sharing the limited resources available to them. Any two species that eat the same thing in the same place will be competing, even if the two never face off. Both will do better if they eat slightly different foods, so they aren't in direct competition.

They were looking for skeletal differences to indicate if that was how multiple species of sea cow were able to live in harmony. Based on their skull and jaw shape, species living in the same areas did seem to specialize in different types of sea grass, so they probably weren't competing for food.

"We were able to look at the shape of their snouts, their teeth, their body size — we looked at those kinds of measures, and that shows us that these animals had strong ecological differences and were likely feeding on different kinds of sea grasses," Pyenson said. "Some would eat different sized roots; some would eat different sized stems."

They were able to specialize in one type of food because habitats were once dominated by several species of sea grass, whereas today sea cow habitats are limited to one or two, which therefore limits the number of sea cow species living there. This loss of species diversity is seen in other areas of the fossil record, too, Pyenson said.

The study was published online Feb. 9 in the journal PLoS ONE.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus