Dueling Skulls: Triceratops Controversy Continues

The debate continues over how many species of horned dinosaurs existed. A new paper concludes that Triceratops and Torosaurus were different species and not, as previously argued, two different age ranges of the same species.

Nicholas Longrich, a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University, says an analysis of 35 skulls and fossil distribution patterns provided signs that the Torosaurus was its own creature, and not simply the mature version of Triceratops.

Longrich's paper, appearing in today's (Feb. 29) issue of the journal PLoS ONE, rebutted the arguments of other researchers including John Scannella, a graduate student at Montana State University.

Triple threat

More than a dozen species were originally delineated in the Triceratops genus. Having been culled from them, the remaining Triceratops species, including Torosaurus, should be consolidated into one, Scannella contends.

The shapes of the two species' heads were slightly different, as were their frills and horns, but Scannella says the different skull forms could be explained by different developmental stages — comparable to teenagers and adults. Once Triceratops matured, it looked like Torosaurus.

There are three testable requirements for this to be true, Longrich writes. But, all three need to be true.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

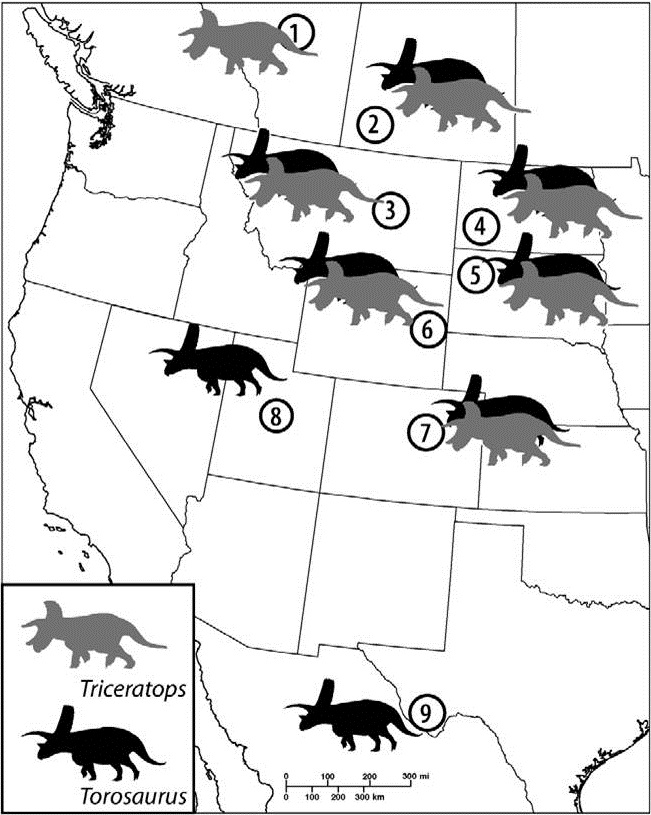

First, the two forms must have the same distribution in the fossil record, since anywhere adults of a species would be found, the youth should be found there as well. Point for Scannella: This seems to hold up based on where Triceratops and Torosaurus fossils have been found, Longrich said.

Mature skulls

Second, if Torosaurus was the mature form, all Triceratops should be immature. To determine maturity of specimens, Longrich examined 35 Triceratops and Torosaurus skulls, including their bone texture and whether individual bones had fused together, which would indicate a fully matured skull.

Longrich found some immature Torosaurus skulls and some fully fused Triceratops skulls, he said. One Torosaurus skull, discovered in the 1800s, was the perfect example: It was huge — more than 8 feet (2.4 meters) long — but Longrich noticed when he examined it that its bones weren't fully fused. "It's getting there, it's full sized, but it hasn't gotten old yet," Longrich told LiveScience. "It's like a teenager toward the end of its growth spurt: It's gotten really big but isn't fully mature."

Scanella noted that fusion of the skull bones could be dependent on things like nutrition, changes over geologic time or individual variation in size: "I think there are some problems with using primarily cranial fusion to determine how mature something is."

Intermediate mix

Third, if Triceratops matured into Torosaurus, researchers should have found some examples of intermediates by now, Longrich argued. Triceratops skulls with shallow depressions in their frills have been found, but Longrich says his analysis indicates they were significantly different from Torosaurus and didn't seem to be developing into that species.

"If there really was a transformation from one to the other, we would find skulls from the intermediate stages," Longrich said. "It's really hard to believe that we just haven't found them."

While we do have a large variety of Triceratops and Torosaurus skulls already, Scannella notes that he is working on a set of more than 100 specimens at the Museum of the Rockies, which are largely undescribed in the literature. He is adamant that "there are numerous examples of intermediate specimens."

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.