Earthquakes Can Ravage Coral Reefs, Study Reveals

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

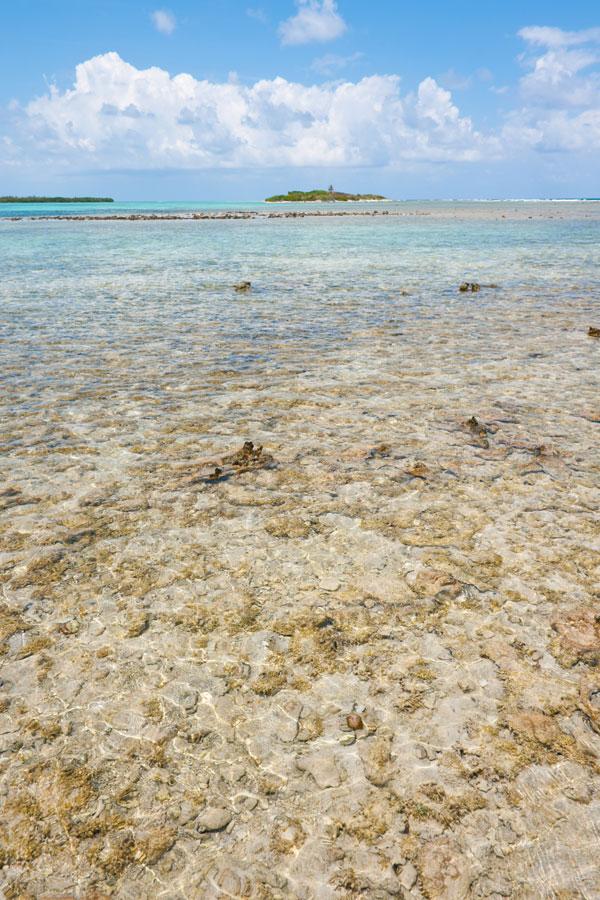

Coral reefs are plagued by a long list of problems that can injure the fragile ocean ecosystems: Ocean acidification due to global warming, plankton blooms, emerging diseases, pollution and overfishing. Researchers have now added one more to that list: earthquakes.

Just as earthquakes can cause devastation on the ground, they can also be catastrophic underwater, a new study has found.

In May 2009, a 7.3 magnitude earthquake hit the western Caribbean, causing avalanches in half of the lagoonal reefs in Belize studied by Richard Aronson, head of the department of biological sciences at the Florida Institute of Technology. It was, however, not the first event to wipe out large portions of the reef.

Aronson and his team have been studying the same 144-square-mile (373 square kilometers) area for more than 20 years and their data provide insight on how to better manage the world's reefs to protect them from disasters, both natural and manmade.

"You can't say, we can develop this coastline and leave this one area as an example of coral reef or intertidal habitat," Aronson told OurAmazingPlanet. "Because if something bad happens, then you have nothing."

Series of unfortunate events

The coral reefs along the shelf lagoon in Belize are estimated to be about 8,000 to 9,000 years old, based on Aronson's work. For at least half of that time, staghorn coral dominated the mixture of coral species, until 1986, when white-band disease ripped through seas and oceans, killing many reefs. With 99 percent of the staghorn coral gone, lettuce coral came in throughout the next decade.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Then the episodic El Niño–Southern Oscillation came along in 1998, and the warmer waters it brought to the region bleached the coral — bleaching is a process where coral's symbiotic algae are expelled, turning it white.

The reefs were already weakened from these two events, and to make matters worse, the particular reef Aronson studied is uncemented, meaning it's not securely fastened to the lagoon walls as most other reefs are. Then, in 2009, the earthquake hit.

"The surface just slabbed off," Aronson said, likening it to an avalanche in a ski bowl. He and his team estimated that a similar event occurred about 2,000 to 4,000 years before, and it took that long for the reef to fully recover. "By happenstance we have all of these unprecedented things going on at the same time," he said.

Coral conservation

The reef will return, but it is tough to say what it will be made of and if the former dominant species will come back. There are some juvenile lettuce corals in deeper water, so Aronson said that it's possible they will provide the seed for new corals. However, the recovery will likely take centuries to millennia instead of decades.

One key to conservation, both on land and underwater, will be to have large connected areas — and not just pockets of smaller reefs — to ensure that when one area is devastated there are reserves that can provide seed stock so the damaged area can regrow.

"Corals do have the capacity to adapt just like everything on this planet," Aronson said. "There's some probability that there will be another event of this sort in this area in the next thousand of years. If we're really going to plan for the long term, let's really plan for the long term."

Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus