Primordial Gases Deep in Earth May Reveal How Planet Formed

The same process that gives rise to earthquakes and volcanoes may also have trapped primordial gases from the formation of the solar system deep inside the Earth, a new study finds.

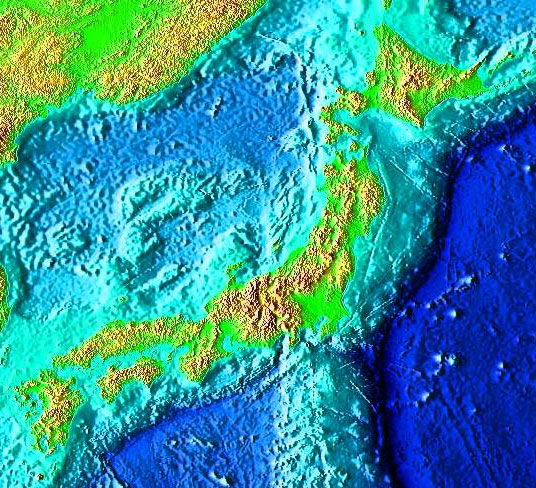

The process, called subduction, occurs when one tectonic plate slides under another. This geologic process happens most famously around the "Ring of Fire," the quake- and volcano-prone loop that traces down the west coast of the Americas and back up the far eastern Pacific. The new study finds that noble gases, a family of odorless, colorless gases including helium and neon, can get caught up in this process. Geologic forces drag the gases out of the atmosphere and into the Earth's viscous mantle layer below the crust.

Earlier research found that the composition of a noble gas, neon, in the mantle, is very similar to the composition of neon in meteorites. Those findings suggested that perhaps Earth's gases came from the same rain of meteorites that caused the craters on Earth's moon. [Fallen Stars: A Gallery of Famous Meteorites]

The new research, published Sept. 25 in the journal Nature Geoscience, calls that conclusion into question, said study researcher Mark Kendrick, an earth scientist at the University of Melbourne in Australia.

"Our study suggests a more complex history in which gases were also dissolved into the Earth while it was still covered by a molten layer, during the birth of the solar system," Kendrick said in a statement.

Gassy Earth

The mantle itself is at least 3 miles (5 kilometers) below the Earth's surface, and that's if you were to start digging in deep sections of the ocean, where the crust is the thinnest. The continental crust is at least 20 miles (30 km) thick. So Kendrick and his colleagues collected rocks from the mountains of Italy and Spain that were once subducted into the mantle but were later lifted back up by the collision of tectonic plates. These serpentine rocks come in a variety of colors, but they're named for their scaly appearance and frequent green hues. More importantly for Kendrick and his colleagues, serpentines are often well-traveled.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The serpentine rocks are special because they trap large amounts of seawater in their crystal structure and can be transported to great depths in the Earth's mantle by subduction," Kendrick said.

The researchers analyzed the gases trapped in the rocks and found that noble gases from the atmosphere can be trapped in the rocks when they form close to the seafloor. Later, the rocks — and their gaseous payload — get subducted into the mantle, forming a sort of conveyor belt for delivering gases into the depths of the Earth.

The findings are important for understanding how the Earth first formed, Kendrick said.

"Our findings throw into uncertainty a recent conclusion that gases throughout the Earth were solely delivered by meteorites crashing into the planet," he said. Instead, churning geologic forces may have pulled gases into a molten Earth during the very birth of the solar system, Kendrick said.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.