Egyptian Mummy's Curse: Oldest Heart Disease Case

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An ancient Egyptian princess would have needed bypass surgery if she'd lived today, according to researchers who examined the mummy and found blocked arteries in her heart in what's now the oldest case of human heart disease.

And she wasn't the only one: An investigation of 44 mummies revealed that nearly half had evidence of calcification in their arteries, or atherosclerosis. This calcification happens when fatty material accumulates inside arteries, eventually hardening into plaques. If the plaques block the arteries, they can cause heart attacks. If they break off and lodge in smaller blood vessels, the result can be a heart attack, stroke or pulmonary embolism (a blockage of arteries in the lungs).

"Overall, it was striking how much atherosclerosis we found," study researcher Gregory Thomas of the University of California, Irvine, said in a statement. "We think of atherosclerosis as a disease of modern lifestyle, but it's clear that it also existed 3,500 years ago. Our findings certainly call into question the perception of atherosclerosis as a modern disease."

Thomas and his co-authors will present their results this week at the International Conference of Non-Invasive Cardiovascular Imaging in Amsterdam.

Diagnosing the dead

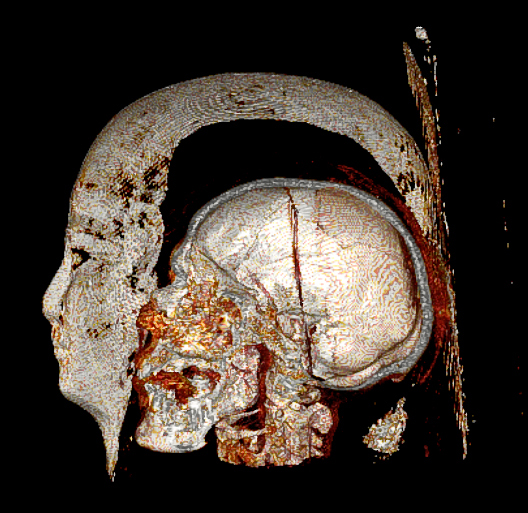

The team used computerized tomography (CT) scans to image the entire bodies of 52 ancient Egyptian mummies. Of those, 44 had recognizable arteries, and 16 still had their hearts in their chests. Twenty of the mummies had evidence of atherosclerosis. In three of the mummies with intact hearts, the coronary arteries that feed the heart were riddled with plaque. [See images of the mummies being scanned]

One of these three mummies was princess Ahmose-Meryet-Amon, who lived in Thebes (now Luxor) between 1580 B.C. and 1550 B.C. The princess was in her 40s when she died.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Humans and heart disease

Ahmose-Meryet-Amon likely lived a more active life and ate a healthier diet than the average American today. She would have eaten lots of vegetables, fruit, wheat and barley, along with some lean meat.

That makes it difficult to understand how two of her three main heart arteries were blocked. Coronary heart disease is often associated with the modern, sedentary lifestyle. It's possible that, as a royal, Ahmose-Meryet-Amon ate more meat, butter and cheese than the average Egyptian. She might have also ingested a lot of salt, which was used to preserve foods, said study researcher Adel Allam of Al Azhar University in Cairo. [10 Amazing Facts About Your Heart]

But the study also points to some unknowns in heart disease risk, Allam said. The princess may have had a genetic predisposition to atherosclerosis. Or her body may have been mounting an inflammatory response against parasites common in ancient Egypt, which might have caused plaques to form as a side effect.

Regardless of cause, the researchers found that, like modern humans, the ancient Egyptians studied had greater rates of atherosclerosis as they aged. Those with hardened vessels had an average age of 45, compared with 34.5 for those whose vessels were clear.

"From what we can tell from this study, humans are predisposed to atherosclerosis," study researcher Randall Thompson of the St. Luke's Mid-America Heart Institute in Kansas City said in a statement. "So it behooves us to take the proper measures necessary to delay it as long as we can."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus