Primitive Sea Creature Sports Eyes Made of Rock

A tiny sea mollusk uses eyes made of a calcium carbonate crystal to spot predators lurking above, researchers say of the first such rocky lenses found in the animal kingdom.

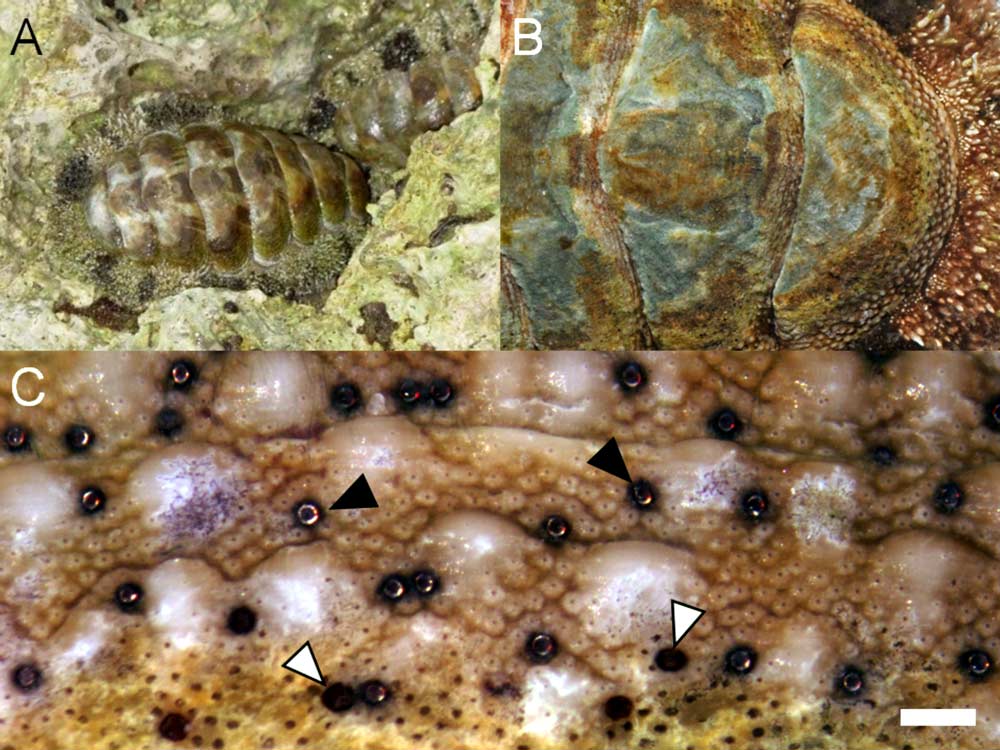

While scientists had discovered the hundreds of eye-like structures on the surface of this armored mollusk, called a chiton, decades ago, they didn't know what they were made of or whether they could actually see objects or just sensed light. [Image of chiton eyes]

"Turns out they can see objects, though probably not well," said study researcher Daniel Speiser, who recently became a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

For comparison, the study found that chiton vision would be the equivalent of humans looking in the sky and seeing a disk the diameter of 20 moons, making human vision about a thousand times sharper than chiton vision, the researchers said. [Jellyfish Have Human-Like Eyes]

Chitons first appeared on Earth more than 500 million years ago. But according to the fossil record, the oldest chitons with eyes didn't emerge until the last 25 million years, making their eyes among the most recent to evolve in animals.

The eyes likely evolved so chitons could see and defend against predators, Speiser said.

To figure out how the stony eyes held up against predators, Speiser and Duke biologist Sönke Johnsen studied West Indian fuzzy chitons (Acanthopleura granulata), which are 3 inches (nearly 8 cm) long, in the lab. Like other chitons, these creatures have flat shells made of eight separate plates with hundreds of tiny lenses on the surface covering clusters of light-sensitive cells beneath.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team realized in a lab experiment that the animal's lenses were made of aragonite (calcium carbonate), rather than proteins like other biological lenses. Then, the duo placed the chitons on a slate slab and as soon as the animal lifted part of its body to breathe, the researchers showed them either a black disk of varying sizes or a corresponding gray slide that blocked the same amount of light. The objects were held just above the chitons.

The blocked light got no response, but when the hovering disk at least an inch (3 cm) or larger came into view the chitons clamped down.

Because the chitons responded to the larger disks and not the gray slides, they seem to be seeing the disk and not simply responding to a change in light, said University of Sussex biologist Michael Land, an expert on animal vision who was not involved in the research. But it's not yet clear if they respond only to the removal of light by the disk as opposed to added light.

The experiments also suggested the eyes had similar abilities in both water and air, suggesting the chiton could see above and below the water.

The results of the chiton study will appear in the April 26 Current Biology.

You can follow LiveScience managing editor Jeanna Bryner on Twitter @jeannabryner.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.