Angry Wasps Capture Intruding Ants, Fly Away, Airdrop Them

What's a wasp to do when ants are ruining its picnic? Pick the little pests up and airdrop them out of the way, according to a new study.

That's the strategy of the common yellow jacket wasp when competing with ants for food, researchers report today (March 29) in the Journal of the Royal Society Biology Letters.

The wasp, also known as Vespula vulgaris, is native to the Northern Hemisphere, but has invaded temperate areas in the Southern Hemisphere, including New Zealand, where the drag-and-drop behavior was observed.

This is the first time wasps have been seen physically relocating ants in an attempt to compete for food, said study author Julien Grangier, a postdoctoral fellow at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. The unexpected flight, which leaves ants confused but usually unharmed, also reveals the invasive wasps' cleverness, Grangier said.

"Our results suggest that these wasps can assess the degree and type of competition they are facing and adapt their behavior accordingly," Grangier told LiveScience.

Ant vs. wasp

Ants and wasps battle relatively frequently, said Robert Jeanne, an entomologist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who was not involved in the study. Wasps have even been seen picking up and dropping ant scouts that show up near nests looking to snack on wasp larvae, he said. But those are defensive — not competitive — behaviors. [Read: How to Eat Ants Without Getting Bitten]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This case here is unusual in that it's really clearly a case of competition," Jeanne told LiveScience.

The South Island of New Zealand is a hot spot for the invasive wasps. In the forests on the island, aphids and other tiny insects feed on beech tree sap. These bugs have little use for the sugars the sap contains, so they excrete those sugars as a sticky liquid called honeydew. Ants and wasps, on the other hand, love honeydew.

Grangier and his colleagues wanted to understand how the invasive wasps compete with native ants for food. So they set up cameras at 48 stations baited with canned tuna (since protein is in shorter supply than sugar in the honeydew-rich forests). All but three of the stations attracted both wasps and ants.

Ant airdrops

Over the course of the months-long study, ants and wasps crossed paths more than 1,000 times. Most of the time, the two species quickly went their separate ways. But in a quarter to a third of cases, the interactions were far less civil.

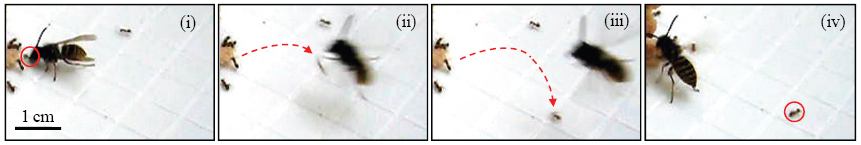

"The first surprise was to see that despite being 200 times smaller, the ants are able to hold their own by rushing at the wasps, spraying them with acid and biting them," Grangier said. "But the most amazing was to observe that wasps, apparently frustrated by having to compete with ants, will pick them up in their mandibles, fly off and drop them away from the food."

The researchers saw the involuntary ant flights 62 times at 20 different bait stations. The wasps didn't bother to take the ants far, usually dropping them only a few centimeters from the tuna. But that was enough. About 47 percent of the time, the discombobulated ants never made it back to the tuna. Even when the ants did make it back, the wasps beat them there 75 percent of the time.

If the ant-dropping was explained by competition, Grangier said, it would increase when the food was in shorter supply. The researchers watched the videos frame-by-frame, counting the number of ants and wasps present during the airdrop episodes.

"We found that, as the number of ants on the food increases, so does the frequency of ant-dropping and the distance the ants are taken," Grangier said. "Our results thus show very clearly that by dropping ants away, these wasps try to facilitate their access to the food resources and to gain more for themselves, and they do it in a very effective manner." [Watch a video of the ant airdrops]

Unwanted insects

The wasps could try to kill the ants, but relocating them is probably a safer option, Jeanne said. For one thing, he said, "there's not a lot of meat on an ant," making them useless as wasp prey. And then there's the tendency of the native New Zealand ant (Prolasius advenus) to spray attackers with an acidic chemical cocktail.

"If the wasp was to bite into an ant to crunch it and kill it, it would probably get a mouthful of some of these compounds," Jeanne said. "It wouldn't be a pleasant experience."

Although the wasps are all over the globe, he said, these airborne food competitions seem to be unique to New Zealand. That may be because wasps are so abundant in the beech forests there that food competition has become particularly cutthroat, Jeanne said.

So far, attempts to beat back the invasive wasp have been unsuccessful, Jeanne said, but understanding the competition between species could help.

"The more we know about the behavior of an invasive species or interactions with other species like this, the more likely we are to find an Achilles heel," Jeanne said.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus