California Storms Fuel Increase in Offshore Oil Leaks

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An area of natural oil and gas seepage off the coast of Southern California became a bit of a gusher last month after a spate of storms battered the state, adding further intrigue to an apparent coincidence of events that resulted in the worst oil-related wildlife kill in the state's waters in two decades.

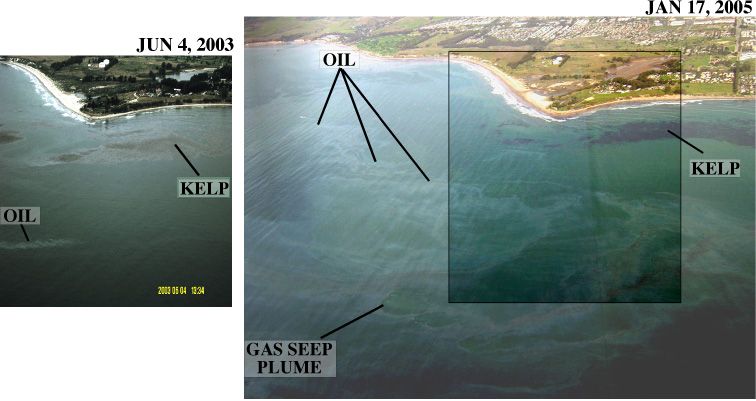

Aerial images released this week reveal the increased output from subsea seeps known collectively as the Coal Oil Point seep field, off the Santa Barbara coast.

The seeps normally put about 4,000 gallons of oil into the sea every day. The output jumped to "many times pre-storm levels," said scientists who are trying to figure out how bad weather would change the flow of stuff from the seafloor.

The seeps are under pressure all the time, creating a natural pump for both oil and natural gas that oozes constantly into the ocean, explained Ira Leifer, a research scientist and oil seep expert at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB).

"We hypothesize that the water from the exceptional Southern California rains flowed along rock layers underground, out under the ocean, and into the rock formations where the oil and gas are seeping from or through," Leifer told LiveScience yesterday. "This increased the driving force, and the seeps became more active."

UCSB geophysicist Bruce Luyendyk said it's also possible that seafloor tar and sediment blockages may have been removed by the storms, causing the flow to increase.

Bird deaths

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In what appears to be a strange coincidence, oil from a different source soaked more than 1,400 birds during a weeklong event just as the offshore seeps were flowing more freely.

As of Jan. 24, more than 600 of those birds died or had to be killed. For each bird found, 10 to 100 likely died at sea, said Jonna Mazet, a veterinarian at the University of California, Davis and an international expert on the rescue and treatment of oiled wildlife.

For wildlife, it was the worst spill in the world since the 2002 wreck of the tanker Prestige off Spain's coast, Mazet and colleagues said. And it was the worst in California since 3,400 birds died after the 1990 American Trader spill off the coast of Orange County.

The oil on the birds was analyzed and doesn't appear to match up with oil from the natural Coal Oil Point seep, said Ken Mayer of the state California Department of Fish and Game's Office of Spill Prevention and Response. The oil on the birds had been weathered after being in the environment for awhile, Mayer explained. Raw oil, as it exists just after emanating from the seeps, contains volatile chemicals that have yet to evaporate away.

"We did eliminate natural seeps offshore" as the culprit, "pretty much," Mayer said in a telephone interview this week. "Nothing's for sure because we haven't had our final meeting yet."

Mayer said some speculation from officials early in the investigation turned out to be wrong, so he and his colleagues are being cautious now.

The oil on the birds appears to have come from some inland source and been washed to sea during the storms, Mayer said. But it still is not clear if the source was an industrial facility or a natural onshore seep. "We're not sure yet," he said.

Keep on seeping

Meanwhile, scientists continue to monitor the Coal Oil Point seep field, which is one of the largest in the world. Its normal 4,000-gallon-a-day release of oil is equal to 100 barrels. It also emits 100,000 cubic meters of natural gas on a typical day.

It's one of many natural oil and gas wells around the globe.

"Seeps are commonly found in oil producing basins of the world, on all continental shelves," Leifer said. "Seeps occur where the rock overlying an oil/gas formation has been fractured by faults or is exposed due to erosion."

Oil and gas migrates through the faults and onto land or into the sea and air. Early prospectors saw them as good places to drill.

They can't be stopped.

"If one poured concrete on one location where there was seeping, the pressure would build up until either the concrete cap was blown away, or the gas escaped from elsewhere," Leifer said.

Leifer also notes that even though the Coal Oil Point seep field is not apparently the cause of the January bird deaths, it is an environmental concern.

"The seeps normally release a lot of oil, they are now releasing quite a bit more, and the oil is going somewhere, and when it gets there, it is affecting the environment, which includes not only birds, but other flora and fauna," he said.

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus