New Transistor Bridges Human-Machine Gap

Humans and machines could be one step closer to merging thanks to a new transistor controlled by the molecule that powers biological cells.

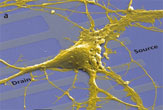

The nano-sized device could be used in medical devices or prosthetics wired directly into the human body.

"Our devices make a bridge between the biological world and the electronic world," said Aleksandr Noy, who developed the transistor along with colleagues at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories in California. "In effect, we made a biological protein talk directly with a nanoelectronic circuit."

Transistors are electronic components that can modulate or switch current on and off in a circuit. To make one that would respond to a biological molecule, Noy and his team borrowed from living cells.

First, they built the backbone of the transistor out of a carbon nanotube between two electrodes. Next, they insulated the electrodes and covered the nanotube with a mixture of fatty molecules called lipids and proteins. The covering formed a lipid "bilayer" — a double lipid membrane — much like those that make up the outer membranes of biological cells.

The researchers then poured a solution of sodium ions, potassium ions and adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, over the transistor while running a voltage through it. In cells, ATP is the primary source of energy. It fulfilled the same role in the transistor, powering the proteins embedded in the lipid bilayer.

These proteins began working, transferring sodium and potassium ions across the bilayer. The charges from the ions created an electrical field around the transistor, which then changed the ability of the transistor to conduct electricity by as much as 35 percent. The higher the concentration of ATP, the more the conductivity changed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Getting a biological molecule to control the electric current in a transistor is a first step toward computers that would interface directly with the brain, Noy told TechNewsDaily.

That could include "futuristic" devices that would translate thought directly to typed words, he said, but could also have a more immediate application in the field of prosthetics.

To develop machines controlled by the mind, "we will need to have a way for our [brain cells] to talk to the electronic systems," Noy said. "I think what we demonstrated is a first step towards that distant goal."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus