Ancient Human Ancestor 'Ida' Discovered

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A discovery of a 47-million-year-old fossil primate that is said to be a human ancestor was announced and unveiled today at a press conference in New York City.

Known as "Ida," the nearly complete transitional fossil is 20 times older than most fossils that provide evidence for human evolution.

It shows characteristics from the very primitive non-human evolutionary line (prosimians, such as lemurs), but is more related to the human evolutionary line (anthropoids, such as monkeys, apes and humans), said Norwegian paleontologist Jørn Hurum of University of Oslo Natural History Museum. However, she is not really an anthropoid either, he said.

The fossil, called Darwinius masillae and said to be a female, provides the most complete understanding of the paleobiology of any primate so far discovered from the Eocene Epoch, Hurum said. An analysis of the fossil mammal is detailed today in the journal PLoS ONE.

"This is the first link to all humans … truly a fossil that links world heritage," Hurum said.

Here is some context for the age of the new primate fossil: Anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) first emerged about 200,000 years ago, but early humans such as Australopithecus afarensis and Australopithecus anamensis, reach back to 3 million or 4 million years ago, or earlier. Humans are thought to have split off from a group that includes chimpanzees and gorillas about 6 million years ago. And a group that includes all the great apes (including us) and old world monkeys (called simians or anthropoids) diverged from new world monkeys in the Eocene, just after the time of Ida. So our primate roots reach back to this time.

History of discovery

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

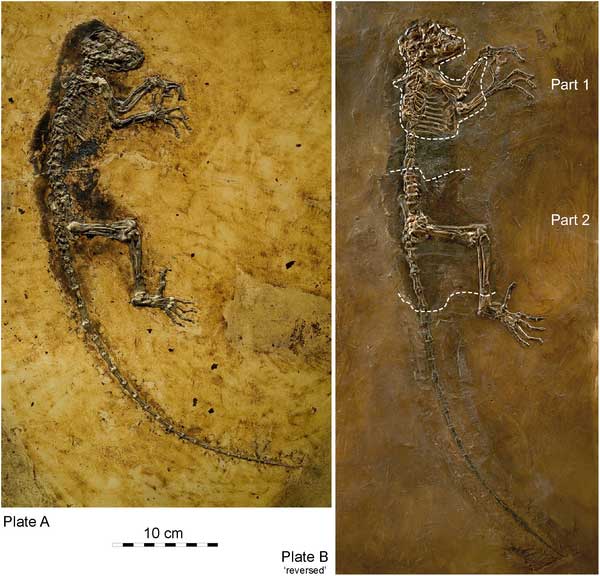

For the past two years, an international team of scientists led by Hurum has conducted a detailed forensic analysis of the fossil. The fossil was apparently discovered in 1983 by private collectors who split and eventually sold two parts of the skeleton on separate plates: The lesser part was restored and, in the process, partly fabricated to make it look more complete. This part was eventually purchased for a private museum in Wyoming, and then described by Jens L. Franzen, part of Hurum's team, who recognized the fabrication. The more complete part has just come to light, and it now belongs to the Natural History Museum of the University of Oslo. Ida was preserved in Germany’s Messel Pit, a mile-wide crater containing oil-rich shale that is a significant site for fossils of the Eocene Epoch. Opposable big toes and nail-bearing tips on the fingers and toes confirm the fossil is a primate, and a foot bone called the talus bone links Ida directly to humans, Hurum said. The fossil also preserved the primate's gut contents, including fruits and leaves. X-rays reveal both baby and adult teeth, plus the lack of a "toothcomb" or a "grooming claw," which is an attribute of lemurs (which are also primates, like us, but are considered more primitive and part of a different family than all the great apes and us).

The scientists estimate Ida was about 9 months at death, and measured about 3 feet in length. Her forward-facing eyes are like ours — which would have enabled her fields of vision to overlap, allowing 3-D vision and an ability to judge distance. She was probably nocturnal, Hurum and his colleagues say.

Ida lived at a time when mammals were evolving quickly on a planet that was basically a vast jungle. Early horses, bats, whales and many other creatures, including the first primates, thrived at this time when the climate was subtropical. The Himalayas were being formed. Death scenario X-rays reveal that a broken wrist may have contributed to Ida’s death — her left wrist was healing from a bad fracture, Hurum said. She could have been overcome by carbon dioxide gas whilst from drinking from the Messel lake: the still waters of the lake were often covered by a low-lying blanket of the gas as a result of the volcanic forces that formed the lake and which were still active. Hampered by her broken wrist, Ida possibly slipped into unconsciousness, was washed into the lake, and sunk to the bottom, where the unique conditions preserved her for 47 million years, Hurum said. A replica of Ida will go on display later this week at the American Museum of Natural History's new "Extreme Mammals" exhibition.

- Evolution's Most Extreme Mammals

- Top 10 Missing Links

- All about Evolution

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus