Top 11 Spooky Sleep Disorders

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

aaaahhhh!

Sleep is supposed to be a time of peace and relaxation. Most of us drift from our waking lives into predictable cycles of deep, non-REM sleep, followed by dream-filled rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep. But when the boundaries of these three phases of arousal get fuzzy, sleep can be downright scary. In fact, some sleep disorders seem more at home in horror films than in your bedroom.

From a syndrome that keeps a person drowsy all day and night to one that may keep you screaming through your snoozes, inside you'll find some of the spookiest syndromes of the night.

Sleeping beauty syndrome

This sleep story does not have a fairy tale ending. Called Kleine-Levin Syndrome (KLS), the rare neurological disorder is linked to excessive amounts of sleep, "spacey" behaviors and demeanor, and confusion. About 70 percent of those affected are teen boys, according to the National Institutes of Health. The syndrome comes in waves, where at the onset a person will sleep most of the day and night, garnering it the name sleeping beauty syndrome; in between such episodes the person seems completely healthy, according to the KLS Foundation. Incidences can last for days, weeks or even months, during which time a person is not only drowsy but when awake they are confused, disoriented and apathetic, with many KLS patients indicating the world seems out of focus; some cases involve uninhibited sex drive.

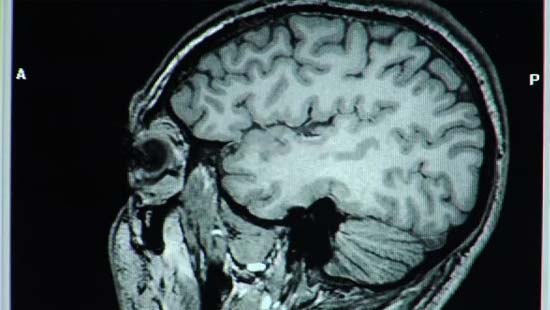

Though the cause is unknown, some scientists think a malfunction in the hypothalamus, which helps to regulate sleep and body temperature, may play a role, according to WebMD. No treatment is available for the disorder.

Scroll up and click "Next" to learn about Nightmare Disorder . . .

Nightmare disorder

Whether it's running from axe-wielding murderers or showing up naked in the school cafeteria, most of us have been jolted awake by a nightmare at some point. When nightmares move beyond occasional annoyance to near-nightly terror, however, you might have nightmare disorder. People with nightmare disorder often wake in a cold sweat with vivid memories of horrible dreams. Their waking life suffers. They may dread sleep.

Stress and sleep deprivation are major nightmare triggers, as are some medications, according to the American Sleep Association (ASA). In severe cases, counseling or sedative drugs might be necessary to soothe the anxiety underlying the bad dreams. For most of us, though, banishing the nighttime axe-murderer is as easy as taking a relaxing bath and going to bed on time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sleepwalking

Up to 15 percent of adults occasionally get up and amble around the house in their sleep. In children, the number is even higher. No one knows what makes some sleepers wander, but stress and disturbed sleep are often factors. So is genetics: Close relatives of sleepwalkers are 10 times more likely to sleepwalk than the general population.

You won't see sleepwalkers shuffling around, arms outstretched; many navigate their rooms with ease and are capable of opening doors and moving furniture. And while waking a sleepwalker won't do them any harm, sleepwalking itself can be dangerous. One study published in 2003 in the journal Molecular Psychiatry found that 19 percent of adult sleepwalkers had been hurt during their nocturnal forays. Falling is the biggest danger, so if you've got a sleepwalker in your house, experts recommend you move the electrical cords and steer your somnambulist away from stairs.

Exploding head syndrome

Okay, exploding head syndrome doesn't actually involve detonating domes. This creatively-named disorder occurs during the onset of deep sleep, when the person is suddenly startled awake by a sharp, loud noise. These noises range from cymbals crashing to explosives going off. To the person hearing them, the explosions seem to originate either from right next to the person's head or inside the skull itself. There's no pain involved, and no danger, either. Doctors don't know what causes exploding head syndrome, but they do know that it isn't associated with any serious illness.

Sleepy hallucinations

We're all used to seeing strange things in our dreams, but what about when we're not dreaming? So-called hypnagogic hallucinations occur during the transition from wakefulness to sleep (just after our head hits the pillow). And hypnopompic hallucinations hit during the waking-up process. People report hearing voices, feeling phantom sensations and seeing people or strange objects in their rooms. Bugs or animals crawling on the walls are a common vision, said Neil Kline, a sleep physician and representative of the ASA.

Sleep-related hallucinations are most common in people with narcolepsy. So while the occasional phantasmic visitation is nothing to worry about, if the hallucinations are accompanied by daytime sleepiness and loss of muscle control when excited or surprised, Kline recommends you see a doctor.

Night terrors

Screaming, thrashing, frantically pacing — night terrors earn their name, both for the person experiencing one and for anyone around during the event.

Unlike nightmares, which arise during REM sleep, night terrors happen during non-REM sleep, usually early in the night. They're most common in children. The person in the midst of a terror may suddenly sit upright, eyes open, though they aren't actually taking in the sights. The person often yells or screams, and can't be awakened or comforted. In some cases, night terrors mix with sleepwalking. Parents have reported children wandering the house in a state of panic. After 10 or 15 minutes, the person usually settles back into sleep, according to the National Institutes of Health. Most don't remember anything about their episode the next morning.

The cause of night terrors is a mystery, but fever, irregular sleep and stress can trigger them. Fortunately, according to the ASA, terrors usually fade after age

Sleep paralysis

During REM sleep, dream activity ramps up and the voluntary muscles of the body become immobile. This temporary paralysis keeps us from acting out our dreams and hurting ourselves. Sometimes, though, the paralysis persists even after the person wakes up. "You know you're awake and you want to move," Kline said. "But you just can't."

Even worse, sleep paralysis often coincides with number 7 on our list: hallucinations. In one 1999 study published in the Journal of Sleep Research, 75 percent of college students who'd experienced sleep paralysis reported simultaneous hallucinations. And these hallucinations, when they occur with sleep paralysis, are no picnic; people commonly report sensing an evil presence, along with a feeling of being crushed or choked. That sensation has given sleep paralysis a place in folklore worldwide. Newfoundlanders know it as the "Old Hag." In China, it's the "ghost pressing down on you." And in Mexico, it's known by the idiom "subirse el muerto," or "the dead climb on top of you."

Even today, some researchers suspect that tales of alien abduction may be explained by episodes of sleep paralysis.

REM behavior disorder

If sleep paralysis is an example of too much immobility, so-called REM behavior disorder is an example of too little. Sometimes, the brain doesn't properly signal the body to stay still during REM sleep. When that happens, people act out their dreams. They may yell, thrash, punch and kick, and even get out of bed and run around. When roused, they'll usually remember their dream, but they won't recall moving around. Given the violence of these outbursts, injuries are common, according to Kline.

REM behavior disorder occurs most often among older adults, and it can be a symptom of Parkinson's disease, a degenerative neurological disorder. Doctors usually treat the disorder with medications that reduce REM sleep and relax the body.

Nocturnal eating disorder

Sure, you may have the willpower to avoid those cookies while you're awake, but what about when you're asleep? People with sleep-related eating disorder go on eating binges at night, only to wake the next morning with little to no memory of the event. Some endanger themselves by chopping ingredients or turning on the stove. Others eat raw ingredients, like frozen food or plain butter.

The disorder is poorly understood, but, like sleepwalking, it occurs during non-REM sleep. Drugs that increase dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with reward and pleasure, can help stop the unconscious nighttime snacking, doctors say.

Sexsomnia

Even stranger than sleep-eating is sleep sex, or sexsomnia. First described in a 1996 case study of seven individuals, sleep sex can range from annoying (loud sexual moans) to dangerous (self-injurious masturbation) to criminal (sexual assault or rape). In at least five controversial cases, men have been acquitted of sexual assault by arguing that they were asleep during the attack.

Most research on sexsomnia have involved small case studies. The largest study, an Internet survey of 219 people who said they experienced sleep sex, is limited because it relied on self-reports. Even so, that study, which was published in 2007 in the journal Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, suggested that sleep deprivation, stress, alcohol, drugs and physical contact with a bed partner play a role. But no one knows why some people respond to these triggers with sexual behavior.

And finally, if you're still awake, one we all suffer from now and then . . .

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus