Charles Darwin: Family Man, Scientist and Skeptic

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

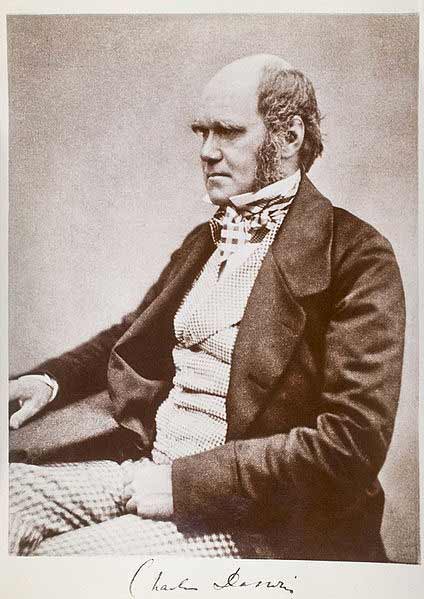

The new film "Creation," starring Paul Bettany as Charles Darwin, opens Jan. 22. The film premiered at last year's Toronto International Film Festival, but was slow to find a U.S. distributor because, according to the film's producer Jeremy Thomas, Darwin's theory of evolution was too much of a "hot potato" in America.

Darwin has indeed been a polarizing figure, especially among some fundamentalist Christians and "intelligent design" creationists who believe that his theory of evolution makes God irrelevant.

The film focuses on Darwin writing "On the Origin of Species," and on his deeply religious wife, Emma, and their torment over the death of their daughter, Annie.

Charles Darwin is of course best known as an evolutionary scientist, but there is a lesser-known side to the man. Steeped in the ways of science, Darwin was also a skeptic who demanded good evidence for extraordinary claims. His skepticism — along with that of his father — would also make for a compelling movie plot.

Darwin's correspondence to friends, family, and colleagues reveals he held very skeptical views about psychics, the paranormal, and alternative medicine. For example, in a Sept. 4, 1850, letter to his second cousin Rev. William Darwin Fox, Darwin was scathingly dismissive of psychic powers (clairvoyance) and homeopathy:

"You speak about Homeopathy; which is a subject which makes me more wrath, even than does Clairvoyance: clairvoyance so transcends belief, that one’s ordinary faculties are put out of question, but in Homeopathy common sense & common observation come into play, and both these must go to the Dogs, if the infinetesimal doses have any effect whatever." (Here Darwin is referring to the illogical homeopathic premise that tiny amounts of a drug are more effective than larger doses.)

Darwin then notes that in order for homeopathy to be scientifically tested, it would need to be studied against a control group: "How true is a remark I saw the other day...in respect to evidence of curative processes, viz that no one knows in disease what is the simple result of nothing being done, as a standard with which to compare Homeopathy & all other such things. It is a sad flaw, I cannot but think in my beloved Dr. Gully, that he believes in everything..."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A year earlier, in a letter dated March 19, Darwin had written of the gullibility of physician James Manby Gully, who had treated Darwin's father: "Dr. Gully was a spiritualist [a member of a group that regularly communicated with the dead] & believer in clairvoyance [also known as ESP or mental telepathy]. He bothered my father for some time to have a consultation with a clairvoyant, who was staying at Malvern, and was reputed to be able to see the insides of people & discover the real nature of their ailments."

To pacify his physician friend, Darwin's father finally agreed to meet with the self-proclaimed psychic who had so impressed Dr. Gully. But, he insisted, he wanted to test the psychic's power for himself.

"Accordingly, in going to the interview he put a banknote in a sealed envelope. After being introduced to the lady he said 'I have heard a great deal of your powers of reading concealed writings & I should like to have evidence myself: now in this envelope there is a banknote—if you will read the number I shall be happy to present it to you.'"

It was a very simple and fair test: if the psychic could see through a patient's clothing and flesh to diagnose diseases, surely she could see through a simple, paper-thin envelope and determine the denomination of a bank note. The psychic refused, saying she was insulted at being asked to prove her amazing abilities: "The clairvoyante answered scornfully 'I have a maid-servant at home who can do that.'"

She did, however, go on to (incorrectly) claim that Darwin's father had horrible internal diseases—perhaps her spite at the skeptic who clouded her psychic abilities.

Darwin's letters provide a fascinating historical context to paranormal claims. 160 years after Darwin and his father debunked homeopathy and fraudulent psychics, such unproven practices are still very much with us. Homeopathic remedies can be found on the shelves of most chain drug stores, and many people today claim to diagnose and treat diseases using psychic powers; they no longer call themselves clairvoyants but instead "medical intuitives."

- The Life of Charles Darwin

- The Future of Evolution: What Will We Become?

- Top 10 Things that Make Humans Special

Benjamin Radford is managing editor of the Skeptical Inquirer science magazine. His books, films, and other projects can be found on his website. His Bad Science column appears regularly on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus