Bite Marks Show T. Rex Teens Fought Viciously

If human teenagers seem terrible at times, be thankful we don't have young tyrannosaurs to deal with.

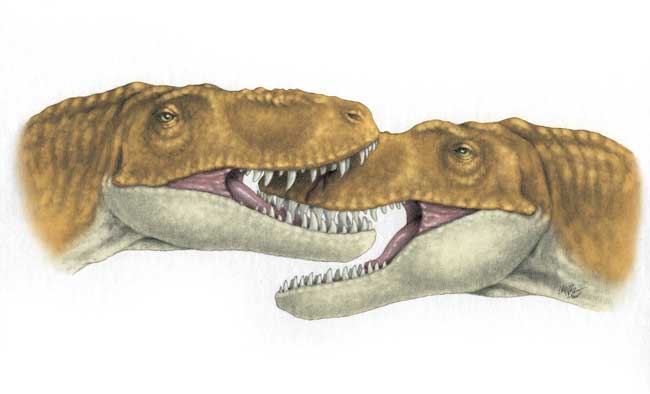

Scientists now find these adolescent predators got into serious battles with their peers, with bites at times puncturing through bone — the kinds of fights we see today in distant relatives of the dinosaurs.

Researchers investigating Jane, the prized juvenile T. rex at the Burpee Museum of Natural History in Rockford, discovered she received a serious bite that punctured her left upper jaw and snout in four places. As severe as it was, the injury wasn't life threatening and eventually healed over, although it left its mark.

"Jane has what we call a boxer's nose," said researcher Joe Peterson, a paleontologist at Northern Illinois University in Dekalb, who helped unearth Jane in Montana in 2001. "Her snout bends slightly to the left. It was probably broken and healed back crooked."

Peterson and his colleagues determined another juvenile tyrannosaur probably caused the damage. Adolescent T. rexes have teeth that are roughly elliptical in cross-section, while adult tyrannosaurs have ones more conical in shape.

"Only a few animals could have inflicted the wound," Peterson said. "When we looked at the jaw and teeth of Jane, we realized her bite would have produced a very close match to the injuries on her own face."

The bite marks were oblong in shape. A crocodile or an adult T. rex would have left different types of bite marks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That leads us to believe she was attacked by a member of the same species that was about the same age," Peterson said. "Because the wound had healed, we think this happened when Jane was possibly a few years younger."

Peterson discovered the bite marks as casts of the upper jawbone were getting pieced together.

"It had more holes in it than the right side, and there was a pattern to the gaps in the side of the face," he recalled. "The surface of the face and edges around the puncture marks were smooth, indicating that there hadn't been a fresh break there and the wounds must have healed over while the animal was alive."

Recently scientists have suggested that what seem like bite marks on some tyrannosaurs might actually be holes in the skull caused by a parasite that afflicts birds today. Such damage might have helped kill off Sue, the famous T. rex at the Field Museum in Chicago. However, Peterson and his colleagues don't believe such a germ caused Jane's injuries.

"The parasite that has been described causes lesions on the lower jaw," Peterson said. "With Jane, the lesions are on the actual face and are not the same type of structures we see on Sue."

"With the recent study of the parasites in the jaw that T. rex might have had, which were likely passed on through face biting, we're seeing a kind of cause and effect," he added.

Jane was young at death, she was still formidable — 22 feet long and 7.5 feet high at the hip, weighing roughly 1,500 lbs, and built to kill with 71 serrated teeth. Still, Jane was much smaller than an adult, and the researchers estimate she was about 11 or 12 years old.

"The study of the bite marks on Jane's face demonstrates that even at a young age this dinosaur was engaging in some pretty serious combat," Peterson said. "We have a pretty good sampling of T. rexes over their growth, and it'd now be interesting to see how their bite forces might have changed over time."

Since Jane had not reached maturity, the combat was likely not over sex. Instead, the researchers conjecture these battles helped young dinosaurs train for later conflicts over dominance or territory, the kind of fighting seen in juvenile animals today.

"It's common to find similar puncture marks on young crocodiles," he says. "We can look at the behavior of these modern living ancestors of dinosaurs and get a good idea of what was going on here."

While dogs and cats and other mammal predators might roughhouse during play, "birds and crocodilians are just a lot more aggressive when interacting," Peterson told LiveScience. "Any time you have a large population of crocodilians, especially ones living in close proximity to each other, you're likely to see missing fingers, pieces of tail, or even parts of faces from these bouts."

"What's exciting here is that instead of just having a skeleton to look at, we're getting a bigger picture of the life of these animals," Peterson added.

Peterson and his colleagues detailed their findings in the November issue of the journal Palaios.

- Image Gallery: Dinosaur Fossils

- The World's Deadliest Animals

- Beasts and Dragons: How Reality Made Myth

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus