Paleo-Case Solved: Ancient Sharks Fed on Giant Reptile

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

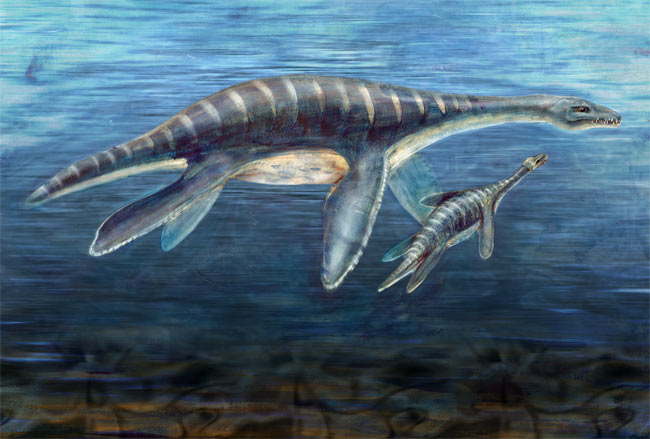

Some 85 million years ago in a shallow ocean, a handful of what amount to miniature great white sharks were pigging out on the carcass of a giant marine reptile called a plesiosaur, a new study suggests.

During this apparent feeding frenzy, some shark teeth got stuck in the plesiosaur's bones, which were subsequently buried and remained undiscovered until a high-school student in Japan found them in 1968. Other shark tooth fossils were found near the bones. Only recently did paleontologists examine and describe the fossils scientifically.

The results, to be published in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, bring to light the diet of ancient sharks. And though the study scientists think the ocean feast was one of scavenging, it's possible the shark gang attacked a vulnerable, elderly reptile, now called Futabasaurus suzukii, while it was alive.

"I'll leave it open for the attack scenario, because we don't know how the animal died," said study researcher Kenshu Shimada of DePaul University in Chicago and the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Hays, Kansas. "So it is still possible that maybe the plesiosaur was wounded or sick, and maybe the sharks took the opportunity and seized it."

Big suzukii

F. suzukii was a long-necked plesiosaur, a group of reptiles equipped with four paddle-like fins used for propulsion in the world's oceans during the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. Shimada estimates the animal spanned some 23 feet (7 meters) from nose to tail tip.

Though Shimada and his colleagues can't go back in time, they pieced together a plausible scenario by looking at the fossil evidence and accounting for the behavior of modern-day sharks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The shark evidence included 87 teeth, five embedded in the plesiosaur's bones and the others buried alongside the reptile. The teeth all belonged to Cretalamna appendiculata, a known shark species with a similar (though scaled-down) streamlined body as that of a great white shark. C. appendiculata individuals likely grew to between 6 and 13 feet (2 to 4 meters) long, compared with a great white, which can reach 23 feet (7 meters). Until now, scientists could only speculate as to the diet of this shark species, with many suggesting it ripped into fish with its sharp, cutting teeth.

"It is still possible they could've eaten fish," Shimada said. "But at least this fossil shows the plesiosaur was one of the food items."

Examination of the teeth suggested they came from at least six or seven different C. appendiculata individuals, some juvenile and some adults.

Loose on the scene

If the plesiosaur carcass had remained for long on the sea bottom exposed to the moving water, bones would have been scattered about. That wasn't the case for this F. suzukii.

"The skeleton is pretty much intact. That suggests to me the time between the death of the animal and when it got buried in the sediment was fairly short, at most a few months; that's my gut feeling," Shimada told LiveScience. With teeth from so many individual sharks, it's likely this was a group event.

Shimada added, "For that reason, I wouldn't be surprised if there were multiple sharks feeding at one particular time."

As for the loose teeth, he suspects as the sharks ripped into the plesiosaur's flesh, several teeth came loose and became embedded in the animal's soft tissues. Such tissues degraded over time, leaving the loose teeth buried alongside the plesiosaur's skeletal remains, he said.

Next, Shimada hopes to piece together other feeding interactions of who ate whom during the Cretaceous Period. "One of my goals is to try to reconstruct the food web of the dinosaur-age ocean. This was one piece of the story," Shimada said.

The research was presented last week at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Bristol.

- Video: Watch a Plesiosaur in Action

- Images: Small Sea Monsters

- The World's Deadliest Animals

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus