Toothy 3-foot Piranha Fossil Found

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

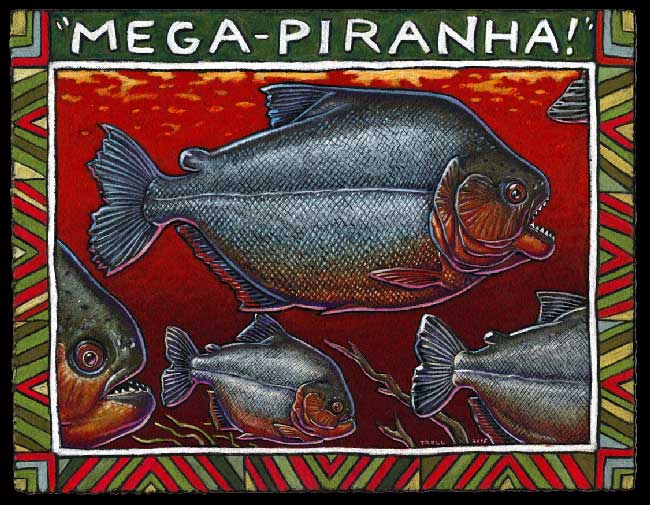

If you thought piranhas were scary, be glad Megapiranha is no longer around.

Megapiranha was up to 3 feet long (1 meter) — a fish-beast four times as big as piranhas living today, studies of its jawbones indicate. It lived about 8 million to 10 million years ago and might have been quite comfortable stalking cartoon animals in an "Ice Age" movie.

Another close relative of the piranha, called pacu (singular and plural), is not so scary. Pacu have squared-off stumps of teeth used for munching veggies. (For the record, tales of carnivorous piranhas eating humans are fictional.)

Now a newly uncovered jawbone of a transition species ties all these teeth together. Named Megapiranha paranensis, this previously unknown fossil fish bridges the evolutionary gap between flesh-eating piranhas and their plant-eating cousins.

Here's what's known:

Present-day piranhas have a single row of triangular teeth, like the blade on a saw, explained the researchers. Pacu have two rows of square teeth, presumably for crushing fruits and seeds.

"In modern piranhas the teeth are arranged in a single file," said Wasila Dahdul, a visiting scientist at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in North Carolina. "But in the relatives of piranhas — which tend to be herbivorous fishes — the teeth are in two rows."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new fossil shows an intermediate pattern: teeth in a zig-zag row. This suggests that the two rows in pacu were compressed to form a single row in piranhas. "It almost looks like the teeth are migrating from the second row into the first row," said John Lundberg, curator at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and a co-author of a study of the jawbone.

If this is so, Megapiranha may be an intermediate step in the long process that produced the piranha's distinctive bite. To find out where Megapiranha falls in the evolutionary tree for these fishes, Dahdul examined hundreds of specimens of modern piranhas and their relatives.

"What's cool about this group of fish is their teeth have really distinctive features. A single tooth can tell you a lot about what species it is and what other fishes they're related to," Dahdul said. Her phylogenetic analysis confirmed her hunch — Megapiranha seems to fit between piranhas and pacu in the fish family tree.

The Megapiranha fossil was originally collected in a riverside cliff in northeastern Argentina in the early 1900s, but remained unstudied until paleontologist Alberto Cione of Argentina's La Plata Museum rediscovered the startling specimen — an upper jaw with three unusually large and pointed teeth — in the 1980s in a museum drawer.

Although no one is sure what Megapiranha ate, it probably had a diverse diet, Cione said.

Other riddles remain, however. "Piranhas have six teeth, but Megapiranha had seven," Dahdul said. "So what happened to the seventh tooth?"

"One of the teeth may have been lost," Lundberg said. "Or two of the original seven may have fused together over evolutionary time. It's an unanswered question. Maybe someday we'll find out."

Piranhas inhabit exclusively the fresh waters of South America, including the Amazon River. Tales of vicious attacks on humans are mythical.

"There are no documented human deaths from piranha attacks," according to the Encarta encyclopedia and other sources. They're known to eat worms and small fish. "A common feeding behavior is to nip off parts of the fins or scales from other types of fish," the encyclopedia explains. "This cropping tactic allows the victim to survive and regrow the injured parts, providing a kind of renewable food resource for piranhas."

- Top 10 Deadliest Animals

- The World's Ugliest Animals

- Gallery: Freaky Fish

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus