More Oxygen Could Make Giant Bugs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Giant insects might crawl on Earth or fly above it if there was just more oxygen in the air, scientists report.

Roughly 300 million years ago, giant insects scuttled around and fluttered over the planet, with dragonflies bearing wingspans comparable to hawks at two-and-a-half feet. Back then, oxygen made up 35 percent of the air, compared to the 21 percent we breathe now.

Not all the insects back then were giants, but still, "maybe 10 percent were big enough to be considered giant," insect physiologist Alexander Kaiser at Midwestern University in Glendale, Ariz., told LiveScience.

Breathe deep

To see if more richly oxygenated air could result in bigger insects, Kaiser and his colleagues investigated whether the current atmosphere was limiting insect size. They compared four species of beetles, ranging in size from about one-tenth of an inch to roughly 1.5 inches.

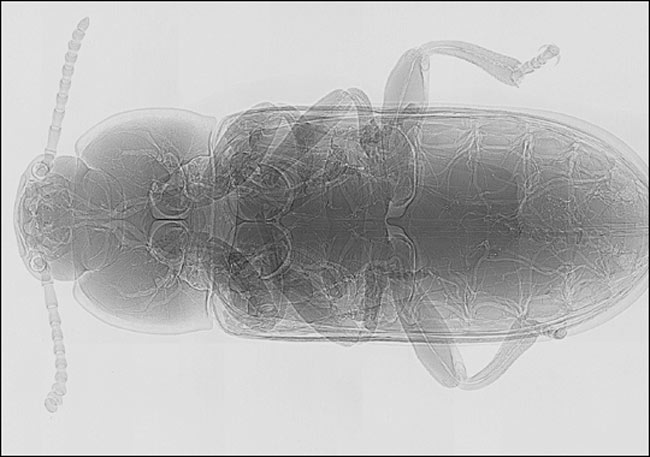

Specifically, the researchers looked at the size of tubes known as tracheae in the insects, which circulate air in and out of their bodies [image]. While humans possess one trachea, insects have a whole system of tracheae that connect to each other and the atmosphere.

As beetle species grew larger, X-rays showed their tracheae took up more of their bodies than the rise in their body size would predict—about 20 percent more. This is because as the beetles grew in size, their tracheae had to grow even more to handle the greater oxygen demands of the insects.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Limiting factor

Eventually tracheae cannot develop beyond a certain size. Based on their calculations, the researchers figure modern beetles cannot grow larger than about six inches. This happens to be about the size of the largest beetle known—the Titanic longhorn beetle, Titanus giganteus, from South America, Kaiser said.

If the atmosphere in the past held more oxygen, tracheae could be narrower and still deliver enough oxygen for a much larger insect. This would lead to a much larger size limit, Kaiser concluded.

The scientists presented their findings at a meeting of the American Physiological Society this week.

- Why Ants Rule the World

- The World's Biggest Beasts

- Backyard Bugs: The Best of Your Images

- How Flies Walk on Ceilings

- All About Bugs

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus