'Germ Islands' Found Floating in Ocean

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Bacteria and other germs latch on to clumps of decaying matter floating in the ocean, creating "germ islands" that could spread disease, a new study reveals.

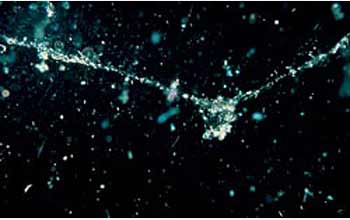

When plants and animals near the surface of the ocean die, they decay and gradually fall to the seafloor. This dead matter can clump together with sand, soot, fecal matter and other material to form what is called "marine snow," so named because it looks like tiny bits of white fluff. Marine snow continuously rains down on the deep ocean, feeding many of the creatures that dwell there.

A group of scientists studying marine snow found that these clumps, or aggregates, may act as island-like refuges for pathogens, the general term for disease-causing organisms or germs, such as bacteria and viruses. (The "island" term comes from the comparison of the existence of pathogens on marine snow with the way insects, amphibians and other creatures establish homes and persist on remote islands in the oceans.)

The scientists are evaluating the degree to which aggregates made up of this decaying organic matter provide a favorable microclimate for aquatic pathogens. These "refuges" seem to protect pathogens from stressors, such as sunlight and salinity (amount of salt in the water) changes, and from predators. They also might provide sources of nourishment for the pathogens.

"If the microclimate is favorable, aggregates likely facilitate the persistence, prevalence and dispersal of aquatic pathogens," said study team member Fred Dobbs of Old Dominion University (ODU) in Norfolk, Va.

The researchers found the bacteria had an increased metabolism (meaning they were more active), and a greater diversity, when living on individual organic aggregates compared with those in the surrounding water. These results indicate that aggregates might be potential reservoirs and vectors for aquatic pathogens.

"We've shown, for example, that vibrios [a type of pathogen] proliferate in aggregates and decline in adjacent, aggregate-free water," the authors wrote in the paper describing their findings, which is included in the May 4 issue of the journal Aquatic Microbial Ecology.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Current models developed to look at the transmission of waterborne diseases and illnesses, however, don't consider the benefits microorganisms gain from hitching a ride on marine snow.

This detritus may skew water-sampling procedures and mathematical models used to predict the transmission of waterborne diseases to humans. When water sampling is conducted — to determine whether recreational waters should be open to swimmers, or whether shellfish beds should be closed to fishers — aggregates lend a hit-or-miss aspect to the testing.

A sample might include only water without aggregates, giving false-negative results that no danger exists.

"The presence or absence of a single aggregate in an environmental water sample could drastically alter the measure of bacterial concentrations," Dobbs said.

The scientists are using the information they have gathered to help predict "how long bacteria can thrive on an individual aggregate and the relationship between the size of the aggregate and the diversity of species found on it," said lead author of the study Maille Lyons, also of ODU.

A better understanding of these relationships could help make water-sample tests more accurate.

The research was funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF)-National Institutes of Health (NIH) Ecology of Infectious Diseases (EID) grant.

- Top 10 Mysterious Diseases

- 10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species

- The Top 10 Infectious Movies

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus