One Key to Bird Flight Discovered

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Powerful forces are exerted on the shoulders of birds where muscles converge. So scientists have wondered why the joints don't dislocate.

Using CAT scans, scientists at Brown and Harvard universities made a virtual skeleton of a pigeon and then calculated all the forces involved. Neither the shoulder socket nor the muscles could keep the wings stable.

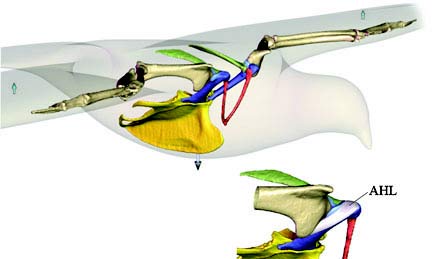

The key, they found, is the acrocoracohumeral ligament, a short band of tissue that connects the humerus to the shoulder joint [image]. The ligament balances all of the converging forces, from the pull of the massive pectoralis muscle in the bird's breast to the push of wind under its wings.

Curious if the same was true of ancient animals, the researchers put some alligators on a treadmill and studied their gaits and used X-rays to make more computer models. The ancestors of modern alligators were closely related to birds.

They found that alligators use muscles, not ligaments, to support their shoulders. A look at fossils of Archaeopteryx, thought to be the first bird, revealed its flight mechanism to be unlike the pigeon, too.

"Our work also suggests that when early birds flew, they balanced their shoulders differently than birds do today," said study leader David Baier, a post-doctoral research fellow at Brown. "And so they could have flown differently. Some scientists think they glided down from trees or flapped off the ground.

- Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly

- Early Bird Used Four Wings to Fly

- Mammals Might Have Soared Before Birds

- Secret of Bird Flight Revealed

- Amazing Animal Abilities

- How Planes Fly

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus