2,700-Year-Old Polynesian Tattoo Kit Found — and the 'Needles' Were Made of Human Bone.

A set of four tiny combs from the Polynesian kingdom Tonga might be among the world's oldest tattoo kits.

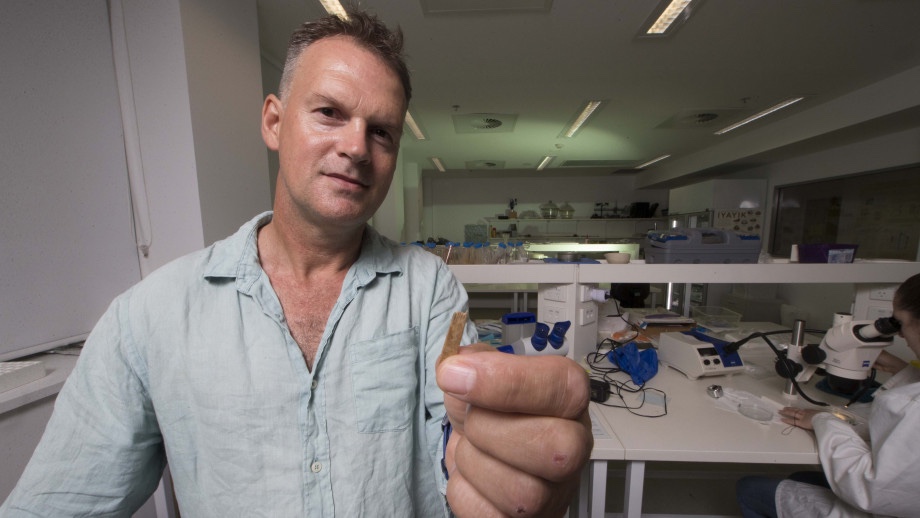

The tools had been sitting in storage in an Australian university for decades. A team of researchers recently reassessed the artifacts and found that the combs — two of which are made from human bone — are 2,700 years old.

Archaeologists have known that tattooing was practiced in several cultures since prehistory. Mummies from Siberia to Egypt have been found with tattoos visible on their flesh. Ötzi the Iceman, a 5,000-year-old mummy found in the Alps, has dozens of tattoos on his body, which some researchers think were inked on for therapeutic purposes.

"In Oceania, we don't have mummies to help us figure out when tattooing first appeared because skin doesn't survive our harsh tropical conditions," the authors of the new study, Geoffrey Clark, of Australian National University, and Michelle Langley, of Griffith University, wrote in an article for The Conversation. "So, instead we must look for less direct clues — such as tools." [Mummy Melodrama: Top 9 Facts About Ötzi the Iceman]

It's only recently that archaeologists have begun to recognize prehistoric tools that were used to make tattoos. In 2016, archaeological experiments showed that 3,000-year-old volcanic glass tools were likely used for tattooing in the Solomon Islands. Last year, another team reported that they found ink-stained tattoo needles carved out of turkey bones from a 3,600-year-old Native American grave in Tennessee. And just last week, archaeologists reported that a 2,000-year-old artifact in museum storage had been identified as a tattooing tool; that needle was made from prickly pear cactus spines by the ancestral Pueblo people in what is now Utah.

The small combs from Tonga were found in an ancient dump during an excavation at an archaeological site on the Tonga island of Tongatapu in 1963. The artifacts had been in a storage facility at the Australian National University in Canberra, and then were assumed lost after a fire. But when the artifacts were found intact in 2008, researchers decided to carbon-date the tools to determine their age.

Tattooing was, and still is, an important practice of people in the Pacific region; the word "tattoo" comes from the Polynesian word "tatau." Men in Tonga were ridiculed if they were not tattooed, Langley and Clark wrote, and many of them traveled to Samoa to receive traditional tattoos when European missionaries suppressed the practice in the 19th century.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the late 18th century, British captain James Cook told Europeans about the elaborate body art he saw during his voyages in the Pacific. He wrote that, in Tonga, tattooing "is done by what we might call puncturation or ingraining with a little flat bone instrument cut full of fine teeth & fix'd in a handle. It is dipt into the staining mixture...and struck into the skin with a bit of stick untill [sic] the blood sometimes follows, and by that means leaves such indelible marks that time cannot efface them."

Langley and Clark think the 2,700-year-old tattoo combs might have been used in a similar way, and the artifacts offer evidence of the deep antiquity of tattooing in Tonga. The researchers also determined that two of the combs were made from the bones of seabirds and the other two from human bone.

"Tattoo combs made from human bone could mean that people were permanently marked by tools made from the bones of their relatives — a way of combining memory and identity in their artwork," Langley and Clark wrote.

Their findings were published in the Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology.

- 25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries

- Strange Designs: 5 Weird Ways Tattoos Affect Your Health

- In Photos: Ancient Skeletons Reveal the Ancestors of Polynesians

Originally published on Live Science.