Greenland's Biggest Fire Is a 'Warning' for Its Future

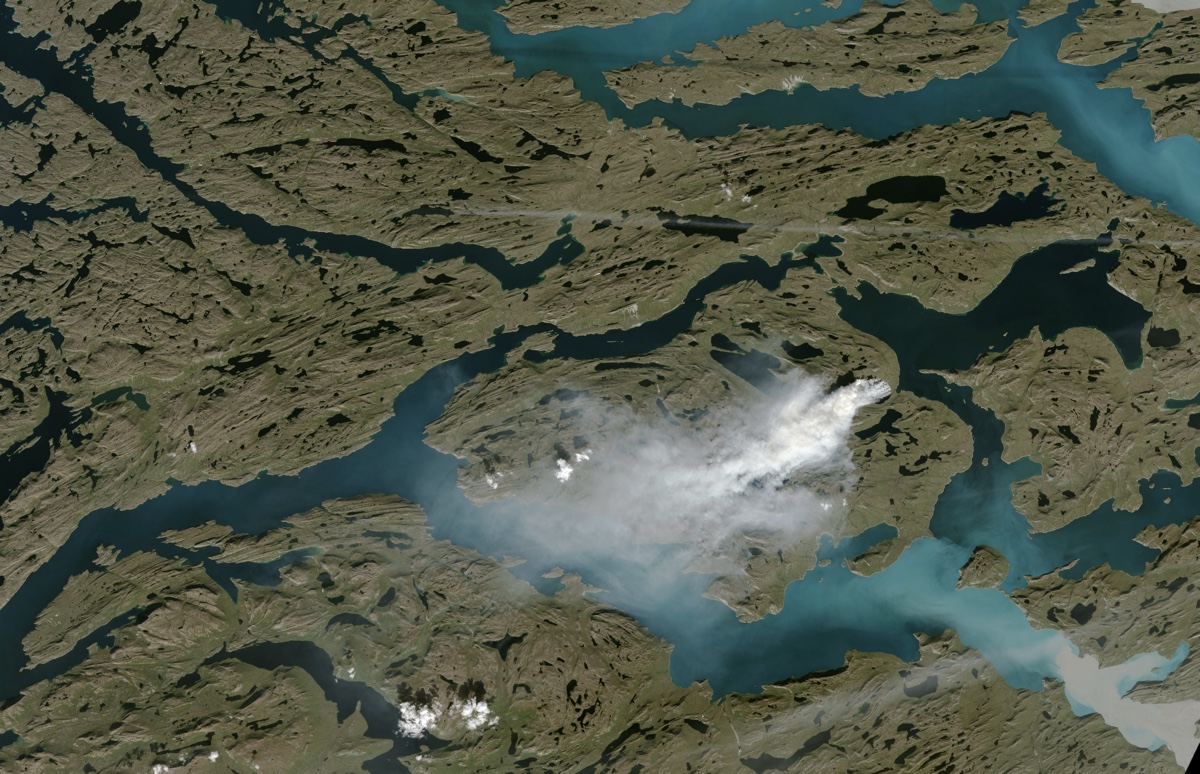

VIENNA — Last summer, puffs of white appeared in satellite images of western Greenland. These were not patches of snow and ice, but rather plumes of smoke from the island's biggest wildfire on record, burning through miles of thawed peatland.

Black carbon particles from smoke plumes can darken Greenland’s vast ice sheet, contributing to more heat absorption and more melting. Scientists who studied the wildfire said that nearly a third of the soot landed on Greenland’s ice sheet. They warned that much bigger blazes could move through the icy island in the future, and the emissions from these fires could contribute to further melting of the already thinning ice sheet.

"I think it's a warning sign that something like this can happen on permafrost that was supposed to be melting at the end of the century," rather than today, Andreas Stohl, a senior scientist at the Norwegian Institute for Air Research (NILU), told Live Science. [Photos: Under the Greenland Ice Sheet]

Stohl and his colleagues presented the results of their study on Wednesday (April 11) here at the annual meeting of the European Geosciences Union.

They started studying the wildfire at the end of July 2017, soon after it was first observed.

There was no lightning activity (one of the primary causes of wildfires) prior to the fire, which was located about 90 miles (150 kilometers) northeast of Sisimiut, the second-largest city in Greenland. It is suspected that the blaze was human-caused, though Stohl noted that peat, under oxygen-rich environments, can self-ignite, even at relatively low temperatures.

The researchers estimated that the fire burned around 9 square miles (2,345 hectares) of land. The NILU-led team also studied how much of the soot from the fire settled on the ice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If you consider that Greenland has the largest ice sheet, apart from Antarctica, it immediately triggers some thinking: What happens if some smoke falls down on this ice sheet?" said Nikolaos Evangeliou, another NILU scientist.

Using a computer model to simulate how soot would have been carried in the atmosphere, the researchers estimated that about 7 tons of an aerosol called black carbon — 30 percent of the total emissions from that fire — landed on the ice sheet.

This amount of carbon didn't have much of an impact on the ice sheet's overall albedo, or reflectivity, Stohl and Evangeliou said. The wildfire, while unprecedented in size for Greenland, was small in comparison to the wildfires that raged over mainland North America last year. (Record-breaking wildfires in British Columbia in 2017 burned more than 4,600 square miles, or 12,000 square kilometers, according to Canadian news magazine Maclean's.) By sending giant smoke plumes into the atmosphere, the North American fires deposited much more carbon on the Greenland ice sheet than the Greenland wildfire, Evangeliou said. However, the Greenland fire was much more effective at dropping carbon onto the ice sheet, he explained.

"If larger fires would burn, they would actually have a substantial impact on melting," Stohl said. And, there's a greater chance of such fires, if more of Greenland's permafrost melts and exposes peat —which is actually the early-stage material used in coal formation, and so it burns easily.

Perhaps more worrisome, these peat fires can burn underground and unnoticed for a long time. Stohl noted that smoldering peat fires in Indonesia can burn for years before they flare up again on the surface.

"We cannot actually be sure that the fires (in Greenland) are out," Stohl said.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus