'Almost Forgotten Disease' Caused Factory Workers' Rashes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A mysterious outbreak of an itchy rash among workers at an herbal supplement factory turned out to be caused by an "almost forgotten disease," a new study from Poland finds.

The outbreak occurred in Poland in July 2012, when 16 employees developed "intensely" itchy rashes on their torsos, arms and legs, the researchers wrote in the report. A month after the outbreak began, a team of researchers was called in to investigate the cause.

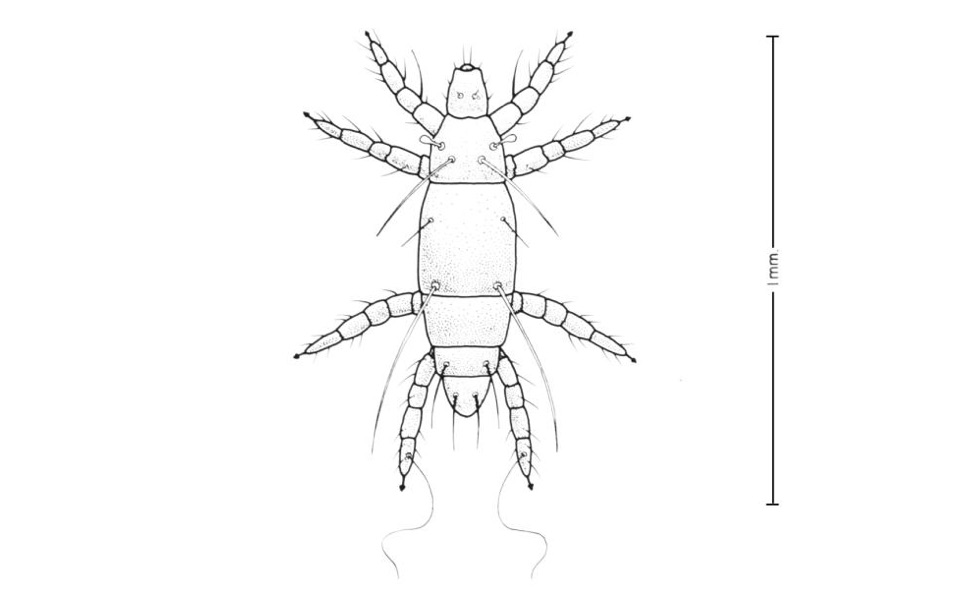

The researchers concluded that the workers' rashes were caused by a type of mite, called the straw itch mite or Pyemotes ventricosus, which has been reported in only three outbreaks since 1981, according to the study, published today (April 26) in the journal JAMA Dermatology. The mites are invisible to the naked eye, and their bites are painless, according to the report. [Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick]

So how did investigators in Poland crack the case?

Although all of the factory workers reported similar symptoms, none initially thought that the rashes were caused by something they were exposed to at work, the researchers said. Indeed, because there is a delay of several hours between the time the mites bite a person and the time the rash appears, it's common for people with these mites to not realize what triggered their rash, the researchers wrote.

Because the workers' family members didn't develop rashes, the researchers concluded that the cause wasn't contagious.

So the researchers investigated the substances that the workers handled in the factory: Were any new materials being used? The employer told the researchers that their manufacturing methods hadn't changed, according to the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the researchers got a clue when, 44 days after the first outbreak, two more workers developed rashes. It turned out that both during the initial outbreak and the second, smaller incident, the workers were handling an herb called Helichrysum arenarium, according to the report.

When samples of the herb were sent to a lab for testing, researchers discovered the mites.

But a question remained: Why did the mite outbreak occur when it did, even though the factory had been working with the herbal supplement for decades? Indeed, many of the workers who had rashes had worked with the supplement in the past and the diagnosis "initially raised many doubts," the researchers wrote.

One major change stood out: In previous years, the workers had handled the herb in the winter months, but in 2012, they handled it in July, according to the study. Previous research suggested that the mites are more common between May and August, the study said.

In addition, the factory had stopped using a pesticide called methyl bromide, the researchers said. This pesticide, which is a gas, was banned in the United States in 2005 because it was contributing to the depletion of the ozone layer, according to the National Pesticide Information Center.

The researchers recommended that the factory be fumigated with another pesticide, phosphine gas, to kill the remaining mites.

Most of the workers' symptoms went away after two weeks, the researchers said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus