'Gilded Lady' and Other Exquisite Mummies on Display in NYC

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

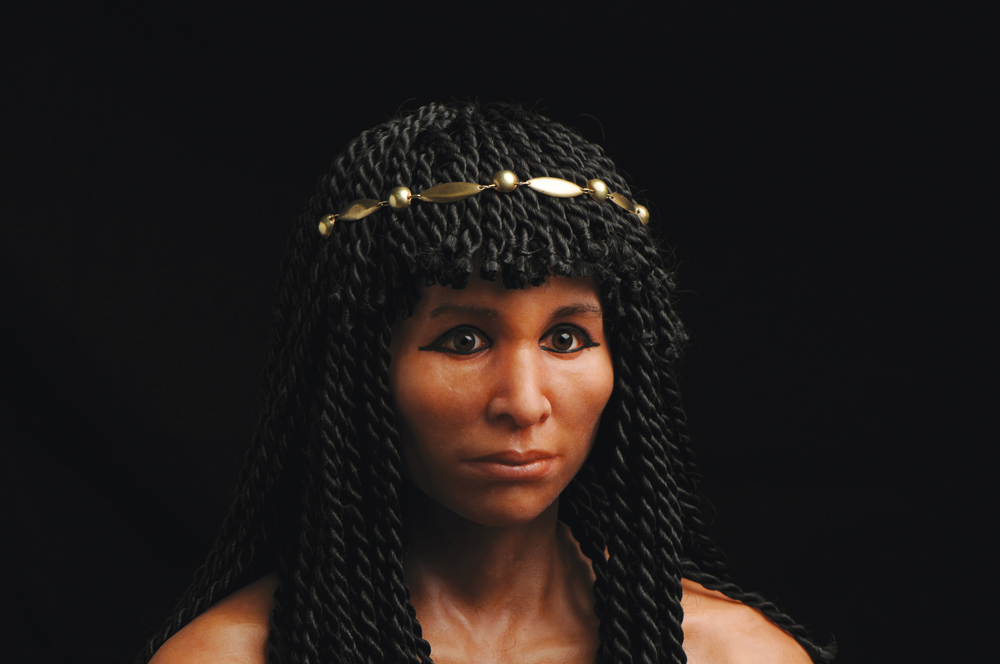

An Egyptian mummy named the Gilded Lady may be more than 2,000 years old, but visitors can gaze into her brown eyes and admire her dark, curly hair at "Mummies," an exhibit opening Monday (March 20) at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City.

Patrons can't see the Gilded Lady's actual face, of course, but they can look at her exquisitely preserved mummy, including a gleaming gold-painted mask. Nearby is a life-size plastic replica of her skull, created from 3D-printed images of a computed tomography (CT) scan of the mummy's head.

French sculptor Elisabeth Daynès studied the plastic skull and created a hyperrealistic statue of the Gilded Lady that looks as if it's about to speak. [See the Gallery of the Mummies from Peru and Egypt]

The Gilded Lady, mummified in Roman Egypt, is one of 18 mummies in the museum's exhibit, which includes human and animal mummies from Peru and Egypt.

"You may think you know something about mummies from cartoons or movies … perhaps those mummies were rising out of their coffins and chasing after the unsuspecting while trailing long strips of cloth," Ellen Futter, president of the AMNH, told reporters Thursday (March 16). "I can assure you, that is not what this show is about. For us, mummies are serious business."

In ancient Peru, mummification was a way to honor, remember and stay connected with the dead. The Chinchorros (5000 to 2000 B.C) are the earliest culture on record to intentionally mummify their dead. Their process was fairly complex: They would remove the dead person's skin and organs, scrape any flesh from the bones and reinforce the skeleton with reeds and clay. Then, they would reattach the skin, paint the deceased black or red, and place a wig and a clay mask on the body's head.

In contrast, the later coastal Chancay culture (A.D. 1000 to 1400) used Peru's dry desert climate to simplify the process, which included burying their dead in an upright sitting position and wrapping them in layers of cloth. They also left gifts in the graves, including food and pots of corn beer, called chicha.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Some people kept mummies in their homes or bought them to festivals," according to the exhibit. "Others brought offerings of food or drink to their loved ones' graves, which sat undisturbed for archaeologists to find centuries later."

Egyptian mummies

Across the world, the Egyptians began mummifying their dead about 2,000 years after the Chinchorros did, probably after seeing it happen naturally in the desert. The desert naturally preserved the first known Egyptian mummy, that of a young woman wrapped in linen and fur. According to CT scans, she suffered from arthritis and hardened arteries before she died about 5,500 years ago.

Over time, the Egyptians created a complex mummification process to prepare people for the afterlife. Organs accelerate decay, so once people died, their livers, lungs, intestines and stomachs would be removed and preserved, wrapped and stored in separate containers, according to the museum. Egyptians left the heart in place, as they believed it was the source of emotion and intellect. However, they removed the brain through the nose because they thought it had little value.

Next, they would dry the body in salt for 40 days, embalm it with resins and oils and pad it to restore a body-like appearance before wrapping it in linen. Many wealthy Egyptians were buried with figurines known as "shawabti," which were thought to do work for them in the afterlife. [In Photos: A Look Inside an Egyptian Mummy]

The "Mummies" exhibit has a handful of mummified animals, including a mummified baboon, gazelle, ibis (a water bird), crocodile and numerous cats, including a few imposters with no bodies.

Many of the specimens are on display for the first time since the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. Although the mummies in the exhibit are treated with respect (guests aren't allowed to photograph the human remains), specimens out in the field are in danger, partly because of climate change, especially in regions once covered with permafrost and ice.

"Once they're exposed — and usually these have usually been covered for 8,000 years or 10,000 years — they don't last long," David Hurst Thomas, the curator of North American Archaeology and the co-curator of "Mummies" at the AMNH, told Live Science. "They thaw out and they are gone."

The exhibit runs until Jan. 7, 2018, before returning to The Field Museum in Chicago.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus