New Icy Island Forms as Arctic Glacier Retreats

As Coronation Glacier on Canada's Baffin Island retreats, it has left behind a new island.

The island, detected with satellite imagery, is made of loose dirt and rocks deposited by the slow-moving river of ice. Typically, a glacial island like this will erode away after the glacier stops feeding it with new sediment (embedded in the flowing ice), glaciologist Mauri Pelto wrote in the American Geophysical Union blog, "From a Glacier's Perspective." The new island, however, might endure, according to research by Pelto, of Nichols College in Massachusetts, and his colleagues.

"The size of the island gives it potential to survive, based on satellite imagery," Pelto wrote. [Images of Melt: See Earth's Vanishing Ice]

Hasty retreat

The Coronation Glacier is on the Cumberland Peninsula of Baffin Island, most of which sits in the Arctic Circle. The glacier is the largest outlet for the Penny Ice Cap, according to Pelto. For decades, the glacier has been on the retreat. Researchers reported in a 1992 study published in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences that the terminus (the end, or toe, of a glacier) of the Coronation Glacier retreated an average of 39 feet (12 meters) per year between 1890 and 1989. (When a glacier retreats, its terminus doesn't extend as far as it did previously, and can result when more ice melts than is replaced by snow accumulations, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center.)

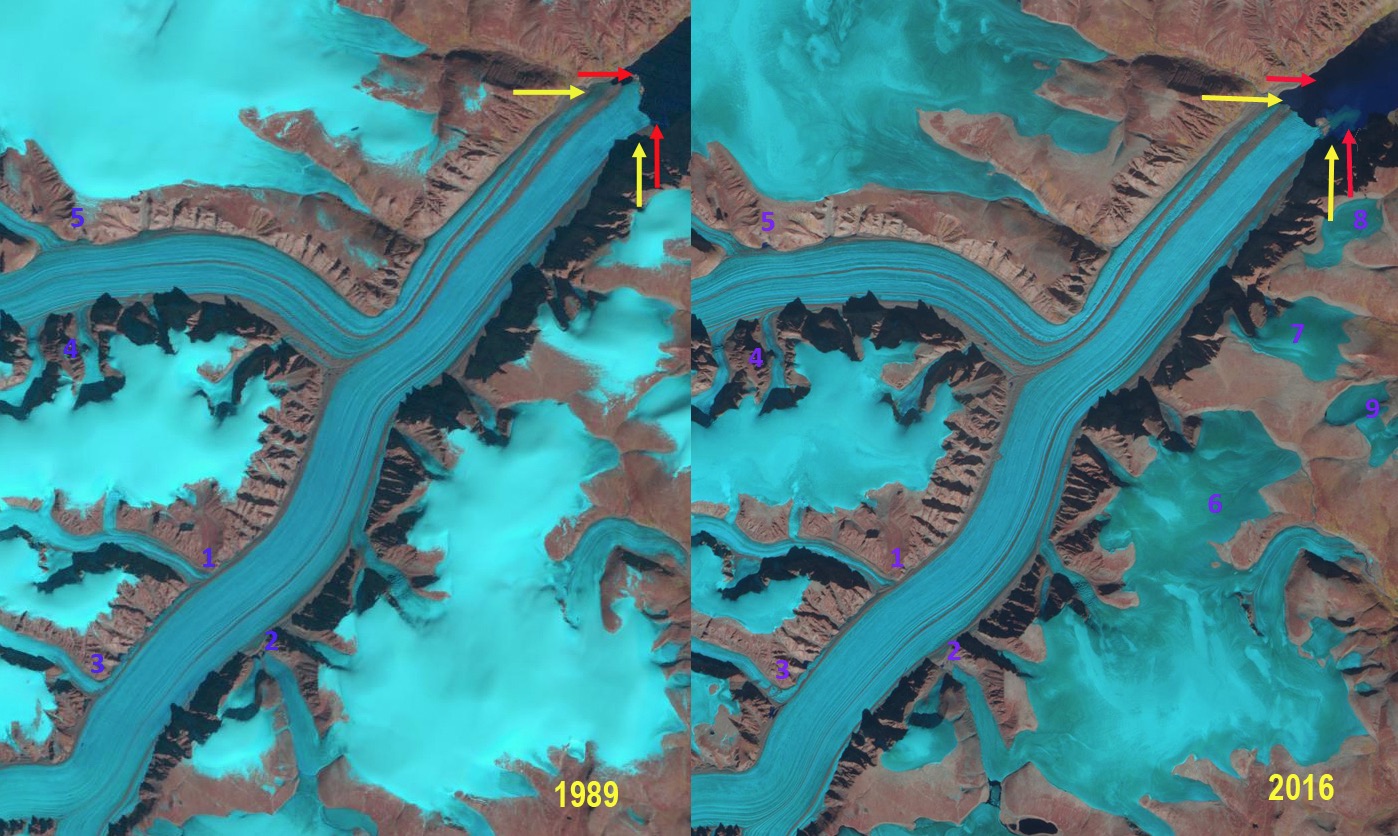

Pelto and his colleagues were interested in how the glacier had been faring since then. Using satellite imagery from 1989 to 2016, they found that the glacial retreat has been speeding up rapidly. In those 27 years, they reported, the average loss, or retreat, has been 98 feet (30 m) each year.

The total retreat since 1989 has been 3,609 feet (1,100 m) on the north side of the fjord into which the glacier empties, Pelto wrote. On the south side, the retreat has been 1,640 feet (500 m). This uneven retreat has changed the landscape sporadically over time. In 1989, for example, there were two islands of glacial sediment at the terminus of the glacier on the north side of the fjord. By 1998, the retreating glacier had pulled away from those islands, and the more northerly of the two was already eroded away, Pelto wrote. By 2000, the more southerly island was gone, too.

Permanent feature?

In 2016, the dynamics of the glacier had created a new island near the southern edge of the glacier's terminus. This position indicates that the glacier's outflow has shifted from the center of the slow-moving river of ice to the south, Pelto wrote. The island is bigger than the ones that disappeared in 1998 and in 2000, he wrote, so it might be a more- lasting feature in the fjord.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"A visit to the island would be needed to shed light on its potential for enduring," Pelto wrote of the island.

The spit of land may persist, but there is increasing evidence that much of the glacier and the Penny Ice Cap will not. The researchers found that the snowpack is decreasing near the glacier, following a trend that scientists have been recording since at least 2004.

The Arctic has been heating up twice as quickly as the rest of the planet. In November 2016, parts of the region experienced temperatures 36 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius) above normal. With such heat, Arctic sea ice formation stalled and briefly retreated. In 2008, researchers reported that Baffin Island's ice cover was at its lowest extent in 1,600 years and might vanish entirely by the middle of the 21st century.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.